An antagonism, a profound enmity, dominates the Middle East: the rivalry that pits Iran against Saudi Arabia. Its roots go back a long way, to before the Khomeini revolution of 1979, to the difference between Shiites and Sunnis, but also to diverse geopolitical interests. The year 1979 marked a watershed because it radicalised not only the Iranian regime but its Saudi counterpart too. The Ayatollahs’ revolution changed the Shiite world, but also the Sunni one, and not just in Saudi Arabia: a good deal of the Muslim world closed itself off. The young crown prince, Mohammad bin Salman (known as MBS), is seeking to open up and change Saudi Arabia, returning to the pre-1979 situation, when there were cinemas and women were not so tightly restricted, and, with his Plan 2030, an economic transformation aimed at reducing reliance on oil.

Will both regimes now change in parallel? Both sides of the equation are undergoing transformation, although success is by no means assured, since both could be subject to destabilisation or generate new resistance to change. MBS wants to transform Saudi Arabia, but this is not a new chapter of the Arab Spring, rather a change instigated from above, and one that has to overcome severe obstacles. MBS is not assured of power. He will need to forge his continuity in the months ahead. The demonstrations that have taken place in Iran come from below, from young and not so young people, frustrated by the economic and social situation, and by the regime’s spending priorities, this time set out with greater transparency, with prodigious sums earmarked for the clergy and defence. And the protests have been marked by the reappearance of the old guard, embodied in the figure of the former President, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

The year 1979 –to which the current Saudi leaders constantly refer (as in Thomas Friedman’s interview with MBS)– was not simply a revolutionary moment in Iran; it also triggered a reaction in Saudi Arabia and other predominantly Sunni countries. It benefitted from the rise in oil prices, putting significant financial resources in the hands of those who wanted to promote various radical and antagonistic versions of Shiite and Sunni Islam in the world, especially the Muslim world. Not that the Saudi regime was by any means a liberal one in 1979. The basis of the regime –the pact between the Saud family and the Wahhabi clergy– became radicalised, and internationalised, in all respects, from the marginal role of women to education, music and the other arts. From such winds a later whirlwind was reaped, from al-Qaeda to ISIS. MBS seems to be willing to dismantle a significant part of this pact. Will he succeed? Saudi Arabia is planning to preside over the G20 in 2020, after Argentina (2018) and Japan (2019), which could be a time for opening up.

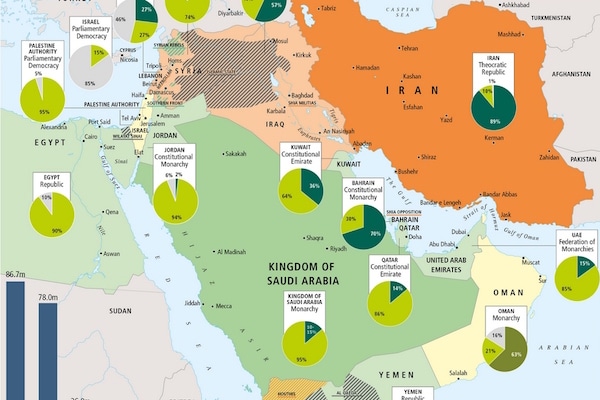

Meanwhile, the invasion of Iraq –numerically mainly Shiite but dominated by the Sunnis– and the destruction of its state in 2003 gifted Iran an unsought victory. Now Trump wants to revise the nuclear deal with Iran not only for reasons of weapons containment, but also to reformat the Middle East; this includes full support for Saudi Arabia, tellingly the first foreign country he visited as President, and with which he sealed an arms sales agreement worth US$100,000. Heavily-populated Iran lacks sufficient military capability to take on the sophisticated Saudi army, whereas Saudi Arabia, which does not have comparable demographic heft, has shown the limits of its air power in Yemen. Riyadh roundly rejects any suggestion that Iran might equip itself with nuclear arms. If it does, the Saudis too will take the nuclear road. And even if it does not, Riyadh is trying to create a regional alliance, an ‘Islamic NATO’, to surround Iran.

Although the geopolitical realities weigh heavily, the success of the reform movements in the two countries could lead to detente. The opposite could also occur, with tension subverting the reform processes and those who resist them engineering a strategy involving more tension. Both countries have consummated their desire and efforts to bring an end to ISIS on the ground in Iraq and Syria, but they have very different visions of the fates they want to befall Syria, Lebanon and Yemen, among others.

They have one thing in common: large populations of young people, enthusiastic about more openness, who had not been born in 1979 and who lack direct experience of previous eras. These young people are frustrated about their future prospects, including in Saudi Arabia, and are totally connected via their mobiles and the Internet, despite censorship and controls. The reformist president of Iran, Hassan Rouhani, has not managed to secure the changes he is seeking –shackled by the parallel state of the Ayatollahs, who are preparing for the succession to Ali Khamenei– or the economic growth that was supposed to follow the partial lifting of economic sanctions in exchange for giving up the nuclear weapons programme. For its part Riyadh fears a Shiite minority in its oil-rich areas. And although it is prodding, the US under Trump is turning inwards and is ceding its role as a determining power in the region. It does not even get on well with Turkey, the other resurgent power in this complex equation. The destinies of Riyadh and Tehran are intertwined, not by a quantum relationship but one that is very real and ideological.