Pro-independence parties won an absolute majority of seats in the elections for the regional parliament of Catalonia, but just under half the votes.

The poll was cast by Artur Mas, the Catalan Prime Minister, as a plebiscite on setting up an independent republic, which he said he now felt legitimated to roll out over the next 18 months, setting him on a collision course with Madrid that has denied a Scotland-style referendum as there is no provision for it in the constitution. Secession is illegal under Spanish law.

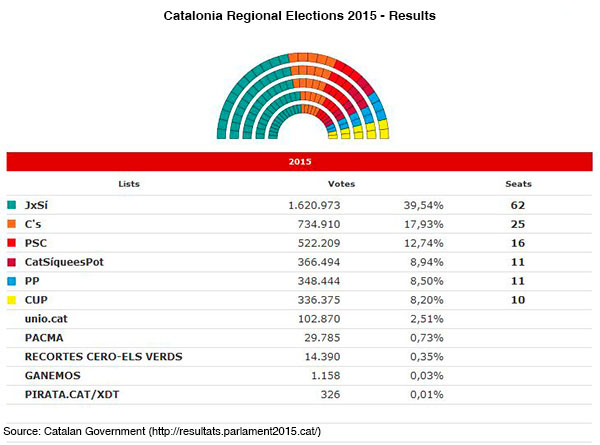

Junts pel Sí (‘Together for Yes’), comprising an unholy alliance of Mas’s centre-right Democratic Convergence of Catalonia (CDC) party and the more radical Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC), won 62 of the 135 seats, and together with the 10 seats of the far-left pro-secession Popular Unity Candidacy (CUP) has an absolute majority. The results were broadly in line with the opinion polls before the election. The pro-independence camp gained almost 48% of the vote. Mas proclaimed to cheering crowds that this gave it the ‘strength and legitimacy’ to push ahead to separate Catalonia from Spain.

“The Catalan issue is going to run for a very long time.”

The second-largest party in parliament is the anti-independence centre-right Ciutadans party (known as Ciudadanos in the rest of Spain), which dislodged the ruling Popular Party (PP) and the opposition Socialists –which have alternated in power at the national level over the last 30 years– as the main force in the region in favour of keeping Catalonia within Spain. The upstart Ciudadanos’s result boded well for its success in Spain’s general election due to be held by the end of the year in which it could emerge as the kingmaker for either the PP or the Socialists.

Support for the PP, which has never been strong in Catalonia, plummeted as it won eight fewer seats than in the 2012 Catalan election, while the Socialists (which headed a Catalan coalition government between 2006 and 2010) lost four seats.

Voter turnout was a very high 77.4%, 10 points more than in 2012 and the highest level since Catalonia began to hold elections in 1980. The turnout for the mock referendum last November was only 37% as anti-independence voters could not be bothered to go to the polling booths. Of the 2.3 million who voted then, 1.897 million were in favour of independence. This time round voters turned out in droves as they realised that a great deal was at stake. The pro-independence camp won 1.952 million of the 4.1 million votes that were cast, not many more and not a mandate to break up Spain.

The region is now clearly split in two, with the pro-independence stuck in their belief that Espanya ens roba (Spain steals from us) as they are convinced Catalonia, the economically most dynamic region, transfers too much tax to Madrid and does not get back enough, and that on their own life would be better.

Dire warnings of the consequences of a victory for the independence camp, including being excluded from the EU and the euro zone (Catalonia would have to re-negotiate) and threats by banks and businesses to relocate outside of Catalonia, did nothing to deter those who want to break away from Spain, but was probably an important factor in getting people out of their homes to vote for anti-independence parties.

What happens now? Mas, for his part, intends to establish a Catalan Foreign Ministry, a Tax Agency, a Central Bank and other entities pertaining to an independent state, tantamount to a state (Catalonia) within a state (Spain).

The central government meanwhile is arming itself with weapons to stop this happening. Last week the Constitutional Court suspended Barcelona’s plan to create its own Tax Agency. Article 161.2 of the Spanish Constitution allows Madrid to challenge any resolution taken by Spain’s regional governments or parliaments and provides for the immediate suspension of the challenged law should the Constitutional Court accept to study the matter, which it did.

The PP also fired a shot across the bows of the Catalan government by presenting in parliament an ‘urgent’ bill –which would be fast-tracked– that would give the Constitutional Court powers to fine or suspend elected officials and civil servants who fail to comply with its rulings.

Both the PP and the Socialists have no truck with the creation of an independent Catalan state. Some Catalans have called for the EU to broker a deal between Madrid and Catalonia. The chances of this happening are very slim –the European Commission sees the problem as an internal one– and even if it went ahead there is a yawning gulf in the positions of the two sides. European governments would not defend Catalonia’s position as it risks opening the door to a contagion effect.

The Spanish Prime Minister, Mariano Rajoy, has ruled out reforming the constitution during the few remaining months of the legislature, and even if he did –in order to recognise Catalonia’s ‘singularity’ and give the region more powers– this would not satisfy the aspirations of the pro-independence camp, which is bent on breaking away from Spain, whatever the cost and ignoring the risks.

Giving Catalonia some kind of special status in the constitution (the Basque Country has one, and its independence movement has piped down) would also run the risk of opening up a Pandora’s Box of competing claims from other regions. The Catalan issue is going to run for a very long time.