Early this year, U.S. News published the 2018 Best Countries ranking that aims at classifying countries according to how these are perceived in terms of adventure, citizenship, cultural influence, entrepreneurship, heritage, movers, open for business, power and quality of life. Countries’ assessments are made by a selection of 21,117 individuals (elites, business decision-makers and the general public) from 36 countries in four regions (the Americas, Asia, Europe and the Middle East and Africa).

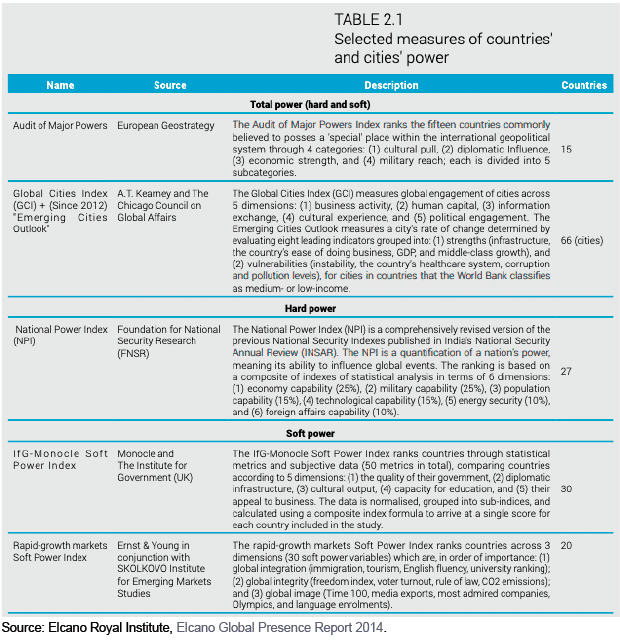

U.S. News power sub-ranking is an additional contribution to a quite large list of power rankings and indices. Some of them were surveyed in our 2014 Elcano Global Presence Report and fairly new indices, such as the Soft Power 30, have also been compared to the Elcano Global Presence Index.

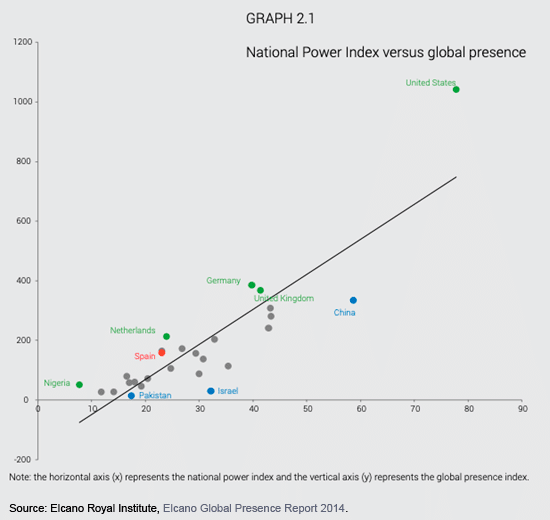

The comparison of rankings or index values of power with those of global presence might be showing which countries are punching above or below their weight. Countries with a high global presence (above the average) but low levels of power (below the average) punch below their weight as they do not transform their volume of international projection into the exertion of influence. Whereas, nations with high levels of power (above the average) and relatively low levels of global presence (below the average) are being able to transform a fairly scarce global or regional presence into power.

A comparison of the National Power Index (NPI) with the 2013 Global Presence Index revealed somehow intuitive results. European countries are, in general terms, fairly mediocre boxers: Germany, the UK, the Netherlands or Spain tend to punch well below their weight. However, some emerging countries as well as key geopolitical spots like China, Pakistan or Israel tend to exert high doses of influence despite a comparatively low level of international projection.

When limited to soft power (and therefore excluding hard, military and/or economic influence), the power-presence comparison shows quite different results. A compared analysis of the Elcano Global Presence Index results and those of Soft Power 30 picture old powers as better trained for exerting soft power. The United Kingdom –that toped the Soft Power 30 ranking at that moment, in 2015–, Germany, Finland or New Zealand would be punching above their weights while lighter weights such as Brazil, Turkey, China, Spain or South Korea played in lower categories.

These different results can be explained, of course, with the very different methodologies behind different indices but, also, they could be showing that there are very different types of power (hard, soft, but then again many other subcategories) that are being exerted in different ways by different actors.

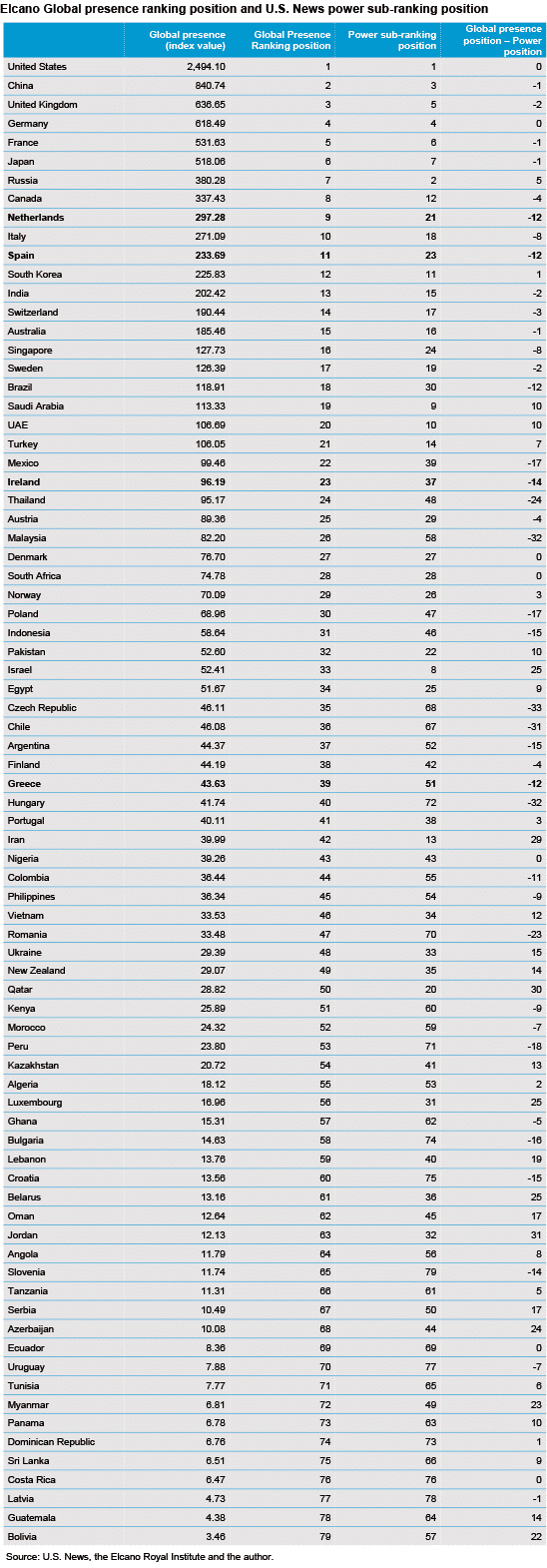

One of the added values of comparing the U.S. News power sub-ranking with the global presence classification is that it allows for the analysis of up to 79 countries.

Results are similar to those of the NPI-Global presence comparison: despite the fact that European countries and other ‘old powers’ still top the power ranking, they appear to be loosing track given their relatively higher positions in global presence (vs. power). This includes countries such as Japan, the UK, Canada, Italy, Switzerland, Sweden, Austria or Finland. In this group, some countries show very high divergences between their two rank positions: the Netherlands (-12), Spain (-12), Ireland (-14) or Greece (-12).

As with the NPI, the group of countries punching above their weight is made of key geopolitical actors (Russia, Turkey, Pakistan, Israel, Egypt, Iran, Ukraine) and/or energy resources providers (Norway, Qatar, Kazakhstan, Algeria, Oman), financial hubs (Luxembourg, Panama) and big or medium-sized emerging economies (Vietnam).

It should be noted, however, that this power sub-ranking is based on individual surveys, and therefore on perceptions. In this sense, it might be important to reflect on the difference between countries’ power and one’s perception of countries’ power… We’ll leave that for another post.