Two years ago, in the summer of 2017, a dispute between Arab neighbours was on the point of escalating into a military conflict. Today it has turned into a battle of sports rights that extends as far as the main international competitions, including Spain’s top-flight football competition, La Liga.

A few days after Donald Trump’s visit to a Saudi Arabia in May 2017, the official Qatari news agency, Wakalat al-Anba al-Qatariya, published some statements by the Qatari head of state expressing support for Iran and the Muslim Brotherhood and criticising various Islamic countries such as Saudi Arabia, Egypt and the United Arab Emirates. The Qatari agency reported that these statements were false and the government issued a press release claiming that the agency had been hacked ‘by an unknown agency’. Notwithstanding, numerous media outlets –such as Sky News Arabia and al-Arabiya– gave them credence and turned them into the subject of a bitter debate. Two months later, Qatar accused the UAE intelligence service of being behind the cyberattack, but diplomatic tension throughout the Middle East was already on a knife-edge. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, Egypt and Libya broke off diplomatic relations with Qatar; this was particularly damaging in the case of Saudi Arabia because it also severed all air, sea and land commerce with its neighbour, whereby Qatar had received 40% of its food imports. Iran reacted by scrambling various aircraft to supply food to its Arab ally.

Rarely had relations between neighbouring countries in the Arabian Peninsula gone so badly, destabilising 20 years of alliances and differences in the Arab world. When mid-way through the 1990s Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani deposed his father –who maintained good relations with the Saudi royal family– and Qatar discovered that its reserves of natural gas were the third-largest in the world, the balance of power in the region changed. Qatar took on greater importance in the Gulf energy map and went into partnership with Iran in extracting the gas reserves, which are in fact located partly in Iranian waters and partly in Qatari waters. In 1996, Saudi Arabia was accused of abetting the failed coup attempt that sought to return power to the Emir’s father, Sheikh Khalifa. Meanwhile, links between the UAE and Saudi Arabia became stronger the more points of common interest their respective leaders found.

Qatar’s soft power

In Qatar both Emir Hamad bin Khalifa and his son Tamim –who succeeded him in 2013 after his brother, Jassim, renounced the throne– pursued a policy of underpinning their legitimacy abroad and strengthening their soft power. They did so by increasing spending on development aid, hosting international conferences such as the WTO (the Doha Round, in 2001) and the conference on climate change (COP18, in 2012) and investing in the luxury sector in London: Harrods, various hotels, the Shard, Cornwall Terrace, as well as investments in the London Stock Exchange and Barclays bank. In the words of the BBC, ‘the Al Thanis own more properties in London than Queen Elizabeth herself’. But most importantly, in 1996 Qatar launched the Al Jazeera (literally ‘the peninsula’) news channel, which has had a marked impact on public opinion in the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region over the past two decades, especially concerning the so-called ‘Arab springs’. Ten years later, an English-language version of Al Jazeera was launched throughout the world.

Sporting events that attract an international audience provide another stage on which the country has focused its soft power. Qatar has organised the Asian Games (2006), purchased the French football club Paris Saint Germain via the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA) sovereign wealth fund (2011), sponsored the shirts of major European football teams (such as Barcelona, Bayern Munich and AS Roma) and succeeded in hosting the FIFA 2022 World Cup –probably by means of bribes, which are being investigated by the French and Swiss judiciaries–, the first to be held in this part of the world, where football has millions of followers. In 2010 Abdullah Bin Nasser al-Thani also bought Malaga FC, and in recent months it has emerged that the QIA is interested in AS Roma and Leeds United.

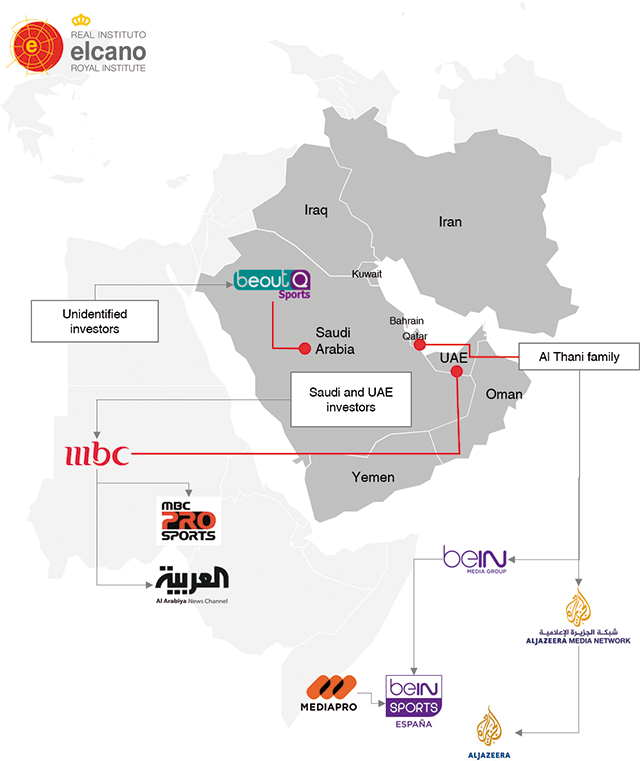

Particularly striking, however, is the enormous investment Qatar has made over the last decade to control the sports TV rights in the MENA region, first with the creation of Al Jazeera Sports (in 2003) and subsequently with its rebranding as beIN Sports (2014), an operation in which it opened franchises with local operators in France (2012), Australia (2014), Spain (with Mediapro, in 2015), Asia (2013) and America (2012). Although its main interests are in sports rights and broadcasts, beIN has tapped into its customer base to extend its audiovisual offering to other types of entertainment, by for instance buying the US film studio Miramax in 2016, with some of its shares being subsequently put up for sale in 2019. beIN’s entertainment signals accompany those of Al Jazeera in the two satellite systems that broadcast to the MENA region; put another way, those who position their satellites to watch football on beIN also receive the output of the news channel, particularly in the signal beamed by the Qatari satellite system Es’HailSat.

Figure 1. The beIN and Al Jazeera signals in the MENA region

| Es’hail 1 (25,5 E) | Eutelsat 8W | |

|---|---|---|

| beIn | 11046 | 11013, 11054, 12604 |

| Al Jazeera | 11065-11678 | 12521, 10971 |

| Others on the same satellite | QatarTV | MBC, Gulfsat and many others |

| Al Kass | ||

| Al Rayyan |

Data verifiable at beIN.net – Frequencies.

The 2017 diplomatic crisis extends to football

The diplomatic crisis between Qatar and the group comprising Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt and Bahrain that erupted in June 2017 led to a highly sensitive situation that could have escalated much further, especially with Yemen in the midst of civil war following the 2014 coup. The allies of the Saudi government demanded that Qatar sever its alleged relations with Hezbollah, the Muslim Brotherhood and Daesh, close a Turkish military base, scale back diplomatic relations with Iran… and close down Al Jazeera. On the pretext of this conflict Saudi Arabia also banned within its borders the sale of subscriptions to the Qatari beIN Sports channel, the only way to access international football –as well as other sporting events– in a country of football fanatics. According to Nielsen, 74% of Saudi citizens are interested in football, making it the fourth most football-obsessed country in the world after Nigeria, Indonesia and Thailand.

The question was: how could it be ensured that this punitive measure against Qatar did not go down badly in Saudi Arabia?

A few weeks later a pay-TV service started to operate in Saudi Arabia under the curious name of beoutQ (a play on words cocking a snook at the Qatari channel), accessible through the Internet and by satellite and with sports content licensed to beIN Sports in this region of the world. There is scarcely any information about who are its owners, although Colombian and Cuban investors have been suggested. The signal probably started to be broadcast via Arabsat –the satellite owned by the Saudi state, which denies having anything to do with beoutQ–, but these days it seems to be only accessible through the Internet (IPTV) with the purchase of a decoder that includes a year’s subscription to the service for less than €100. In no time at all the small decoder boxes could be bought clandestinely in virtually all the countries of the region.

In July 2017 a visit by the US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson to Qatar and the signing by the two countries of a memorandum with measures against international terrorism quelled the diplomatic spat between the Arab neighbours. Mike Pompeo, the current US Secretary of State, and Donald Trump have also endeavoured to defuse the tension. It should not be forgotten that Qatar plays host to the largest US military base in the region (al-Udeid, with 10,000 troops) and in June 2019 Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani’s state visit to Washington included the signing of various trade agreements, among them arms purchases.

Various gestures in recent months indicate an easing of tensions. But while the diplomatic battle between Arab countries was fought out in more sensitive areas, beIN and beoutQ have continued with theirs. And while the Saudi channel superimposed its logo on top of the beIN logo to obscure it, the Qataris started to move theirs around the screen so that the piracy of their channel was evident for all to see. In the commercial breaks during sporting events, beoutQ shows anti-Qatari content, accusing beIN of politicising and monopolising sports rights.

Figure 2. Television sports rights in the MENA region

| Owner | MENA rights | Spanish rigths | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games | COI | beINSports | Eurosport (Discovery) |

| 2022 FIFA World Cup Qatar | FIFA | beIN Sports | Mediapro (2019-2022) |

| UEFA Champions League | UEFA | beIN Sports | Telefónica Movistar |

| La Liga (Spain) | La Liga | beIN Sports | Telefónica Movistar (2019-2022) |

| Premier League (England) | Football Association Premier League Limited | beIN Sports (2019-2022) | Perform Group (DAZN) (2019-2022) |

| Formula 1 | Formula One World Championship Limited | Abu Dhabi Media (MBC Action) (2019-2023) | Telefónica Movistar (2019-2020) |

Source: the author.

Unsurprisingly, the economic impact on this market made itself felt immediately. BeIN, which owns the rights to broadcast Formula 1 races in the region until 2019, announced that it would not take part in the auction to renew them due to the situation created by beoutQ, after which the Saudi-UAE concern MBC acquired them unopposed. Formula One Management, affected by the lack of competition in the auction, condemned the way the F1 championship signal was being pirated by the Saudi channel.

Harmed by the loss of income and uncertainty in the market for TV sporting rights, beIN announced in June that it was laying off 300 staff at its headquarters in Qatar. In recent months, beIN has launched legal action against Saudi Arabia for the economic damages caused by beoutQ to the tune of US$1 billion.

The case of beoutQ has led the US to include Saudi Arabia on the 2019 watchlist of countries accused of illegal activities against intellectual copyright; the names of such countries are periodically published in their infamous ‘301 reports’, which are so well known in Spain. The US Department of Trade warns that the beoutQ decoders are easily available in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere in the region and that the country is not taking the appropriate measures against the channel’s audiovisual piracy. Just this summer, a joint statement released by the Spanish, Italian, English and German professional football leagues as well as UEFA and FIFA condemned ‘the ongoing theft of our intellectual property’. The group, comprising seven organisations affected by the activity of beoutQ, has been unable to find any firm of lawyers prepared to take their case to the Saudi courts:

‘We spoke to nine law firms in KSA, each of which either simply refused to act on our behalf or initially accepted the instruction, only later to recuse themselves… We feel we have now exhausted all reasonable options for pursuing a formal copyright claim in KSA and see no alternative but to pursue beoutQ and a solution to this very serious problem of piracy by other means.’

Despite John Whittingdale, the former British Culture Secretary, describing the channel as ‘one of the biggest and most brazen piracy operations the world has ever seen’, it seems unlikely that the case of beoutQ will be any more than a footnote to the diplomatic crisis of 2017, and probably the intervention of the US Trade Department will prove to have more influence than the European authorities when it comes to thwarting the beoutQ signal. Meanwhile, another opportunity to harness sport as a diplomatic tool has been lost: FIFA proposed that the 2022 World Cup should see an increase in the number of participating teams to 48 (16 more than normal), on condition that some of Qatar’s neighbours be allowed to host some of the additional games. The timing was not ideal. The world’s supreme football body withdrew the proposal two months ago.