If the first round of the presidential elections was a confrontation between an open and a closed conception of France, rather than right against left, the run-off on 7 May between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen will be even more so. With the likely victory of the former, many in Europe are breathing easily. Anyone doubting that this is the battleground need only recall the National Front leader’s words in this campaign: ‘The “globalist” choice is one side, embodied by all my opponents, that seeks to destroy our great economic and social balance, which involves the abolition of all borders, economic and physical. The alternative is the patriotic choice, which places the defence of the nation at the heart of any public decision’. Macron too has sought to escape the left/right dichotomy to put himself forward as something progressive and new. The traditional party system in France has been cast asunder. The centre and extreme right have been reborn. It is also the new against the old, despite the fact that the National Front, with its best results ever, already has a track record. The map of these elections reveals two Frances, with Paris clearly in the first.

The fact that Le Pen has gone through to the second round (although, significantly, not as the winner of the first) indicates –along with other factors such as the good result of the left-wing Jean-Luc Mélenchon and his France Insoumise (‘defiant France’) movement– that something serious is stirring in the depths of French society. Not only because the National Front has managed to trivialise itself and may secure between 30% and 40% of votes on 7 May, but also because this election, like others elsewhere, including the US, pits a France that is on the ascendant against another that is in decline. The latter is rural France, one that is downgraded, undergoing industrial crisis, where a section of young people are unable to find work, predominantly anti-immigrant and anti-European.

The resounding failure of the socialists, who belong to one of the political families that built the current Europe, will have repercussions beyond France. By choosing Benoît Hamon as their candidate the Socialist Party’s militants alienated themselves from voters (as in the UK, and it remains to be seen whether something similar happens in Spain). And the ‘Mélenchon effect’ indicates that something serious is happening on the left, to the detriment of social democracy. The right –the Republicans have no qualms about labelling themselves as ‘the right’– have resisted better, but there is now a bitter fight for their future. For the first time in the Fifth Republic, neither a Socialist nor a Republican (heirs of Gaullism) will have a presence in the second round of the presidential elections.

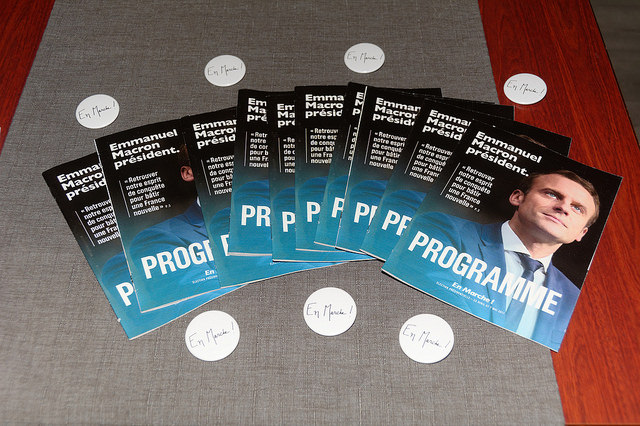

The electoral race for France takes place over five rounds. The two presidential rounds will be followed by two parliamentary votes in June, for which Macron currently lacks a party, although he does have a movement (En Marche!). It is true that this election has decimated the traditional parties and whenever presidential elections have immediately preceded legislative ones, the winner of the former has cleaned up and won a majority in parliament. But these are shifting sands and it may be that a modernising President in the form of Macron will be hamstrung by a new version of cohabitation, hobbling Europe in the process.

The fifth round is the German election in the autumn, because it will determine Europe’s room for manoeuvre, particularly the Eurozone’s, and therefore France’s. In light of the statements coming from both Angela Merkel and Martin Schulz, it does not seem that the elbow room will broaden significantly. The elections in the UK, now irrelevant to Europe, have no bearing on this fifth round, although they too could have an impact on the future of social democracy if the Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party suffers a humiliating defeat and if the only opposition that truly puts up a fight against Theresa May’s Conservatives ends up being the Scottish Nation

France is going to emerge from this electoral fix with a victory for an open outlook, prepared to re-secure the EU with the proviso, as these elections show, that it will not be possible to conduct any reform to the treaties that needs to be submitted to a referendum. France has open wounds. Will Macron manage to bind them and push through reforms that have been put off for too long? This is the big issue, the conflict of interests between nationalist populism and liberal technocracy, as Carlo Invernizzi Accetti argues. The way it is resolved and overcome –by no means an easy task for Macron– is what will render France dependable in a Europe undergoing profound transformation. In order to reconstruct Europe it is necessary to reconstruct France. And vice versa.