Recently, Portland Communications has launched Soft Power 30, an index aiming at classifying countries according to their capacity to ‘softly’ influence others. By means of “positive attraction and persuasion”, a country may exert soft power through a variety of channels such as engagement (diplomatic network, commitment to global development), the appeal of its cultural outputs, its commitment to freedom or human rights, the quality and attractiveness of its educational system, its digital infrastructure and capabilities and, lastly, business friendliness and capacity for innovation.

The combination of over 65 indicators across these 6 fields of soft influence provides a useful tool for analysing international relations in a way that old-school indexes of power –that unveil, mostly, the features of hard power in the Cold War world– can’t.

As mentioned in previous studies, presence is not the same as power. The Elcano Global Presence Index calculates the external projection of countries –regardless this projection is transformed into influence, or not. Moreover, global presence might be soft, but also hard (economic or military) as the 20th century paradigm of international relations actually coexists with a new, more modern, sophisticated and soft way of interconnecting countries.

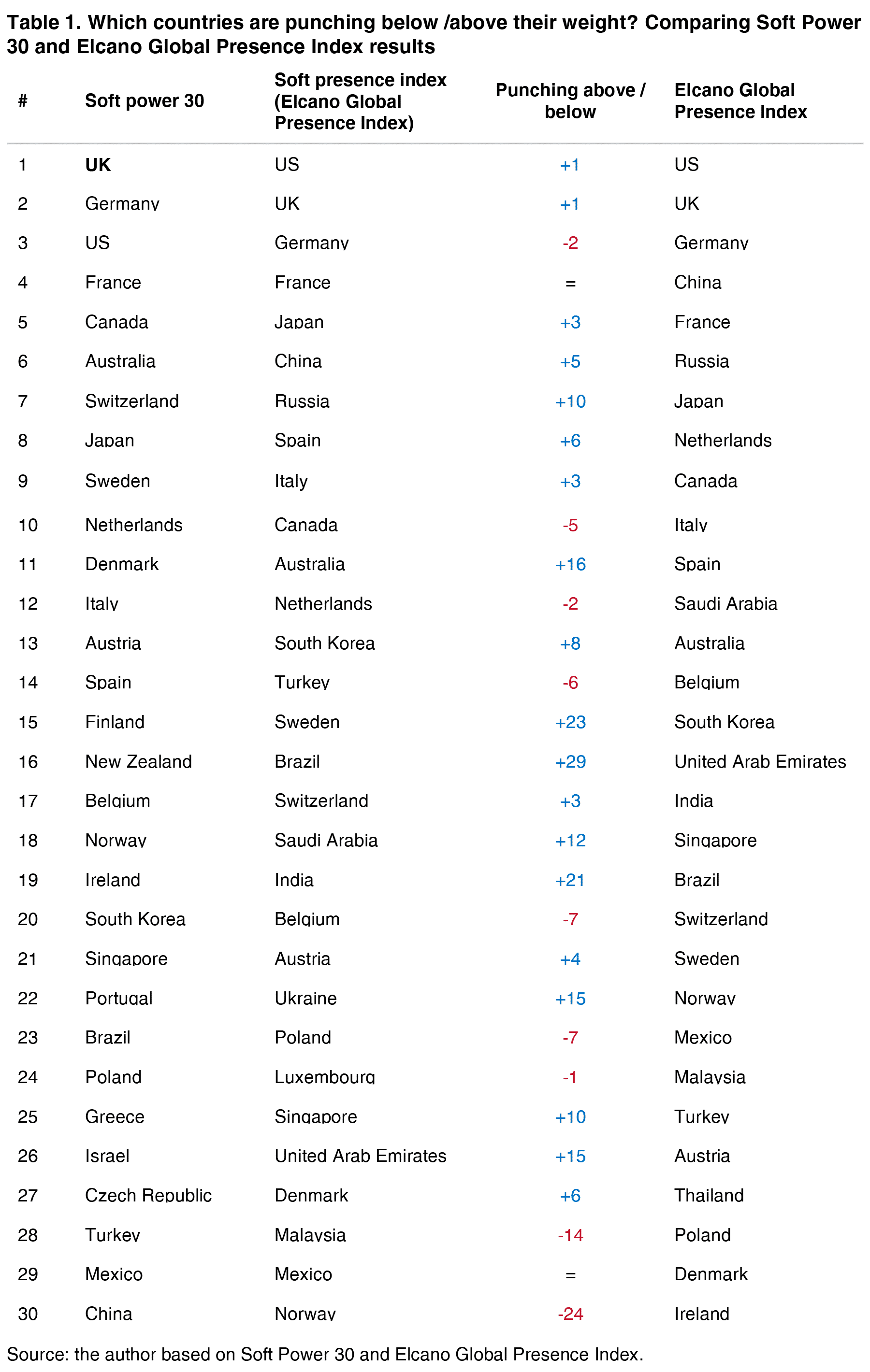

So, even in the soft realm, countries might be just globally present or could be exerting power and influence intentionally or unintentionally. Comparing global presence results –or, more specifically, soft presence– with a soft power index might show to what extent different countries ‘punch below or above their weight’ (see Table 1).

Comparing Soft Power 30 and the Elcano Global Presence Index results. Source: the author based on Soft Power 30 and the Elcano Global Presence Index.

Maybe surprisingly, a comparison between Soft Power 30 and the Elcano Global Presence Index results reveals that old powers are more trained in exerting soft power. The United Kingdom –that tops the Soft Power 30 ranking–, Germany, Finland or New Zealand punch above their weights. On the contrary, lighter weights such as Brazil, Turkey, China, Spain or South Korea play in lower categories.

However, a previous analysis on this issue showed the opposite picture when comparing global presence –including the economic, military and soft dimensions– with measures of power such as the National Power Index. Old European powers –the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands– are loosing track and punching below their weight. On the contrary, emerging countries such as China, Israel or Pakistan do punch above their weight and exert power over the average, despite that their global presence is below the average.

In a few words, maybe emerging countries are catching-up old powers in the economic and military dimensions but (for now) Western Europe still dominates in the soft universe.