Since the November 2011 legislative elections, the Moroccan government led by the Justice and Development Party (PJD) has struggled to keep the economy on track despite the global economic crisis –which has severely affected its main southern EU partners– and the impact of the Arab revolts. The PJD campaigned on economic issues such as growth, employment, redistribution, social welfare, the fight against corruption and the promotion of effective governance, as well as on many religious topics –not always symbolic– that ranged from Islamic financing to taxation on alcoholic beverages. Only after taking office did they appear to realise that moving their economic agenda forwards was not an easy task, and that economic policy was greatly constrained by both the country’s socio-economic situation and an institutional setting that limited their policy-making autonomy.

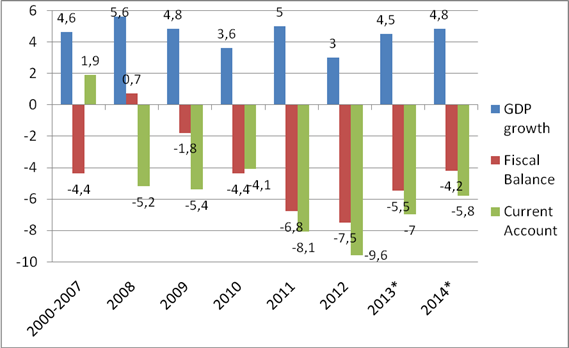

On the one hand, they found an economy that had been growing at an unprecedented and stable rate of around an average 4%-5% during the previous decade (see Figure 1). Reduced growth volatility arose from economic modernisation and a gradual diversification away from agriculture, making the economy more resilient to the recurrent droughts that afflict the country. Despite the evident impact of the international crisis and the Arab revolts on the Moroccan economy, 2011 ended with a 5% growth rate due to that year’s generous rainy season. Inflation was below 1% due to price restrictions in the form of subsidies and price controls in basic goods and services such as oil, gas, electricity, sugar, wheat, public transport and the like. However, there was growing evidence that price tensions were on the rise and that official inflation data could be underestimating a higher erosion of the purchasing power of Moroccan consumers.

Macroeconomic stability, one of the hallmarks of the previous decade, was rapidly deteriorating and transforming into high budgetary and external unbalances. The fiscal balance fell from a surplus of 0.7% in 2008 to a deficit of 6.8% in 2011. The current account, which had achieved a slight surplus in the first half of the 2000s and deficits of around 4% afterwards, registered a decade-high -8.1% in 2011. With international markets closed by the financial crisis, spreading uncertainty in the region and free-falling foreign reserves, the country’s financial profile did not look very bright. The reform agenda was huge and did not converge much with the PJD’s own policy preferences. Population expectations were on the rise at a time when fiscal income was falling, and international oil and food prices were too high for the Moroccan subsidy system to be sustained.

The dilemma confronted by the PJD was similar to that faced by the Islamist parties that took office in Tunisia and Egypt. All of them proved reluctant to reduce food and energy subsidies, as well as other strands of public spending, knowing that their credibility as social benefactors was contingent upon the effective delivery of improved living standards. At the same time, financing needs further reduced their economic policy space, with the IMF imposing conditions to provide the countries with much needed foreign reserves. The Mursi government postponed subsidy reform and led the Egyptian economy to the edge of economic collapse by rejecting the IMF’s conditionality and losing the confidence of the international markets. In Morocco, as in Tunisia, the PJD first took a more ambivalent approach regarding economic policy. It included a pro-market attitude and anti-corruption rhetoric, but also the maintenance of costly energy and food subsidies, increases in public wages and transfers (such as the introduction of a modest unemployment programme) and other expansionary measures.

In 2012 the harsh reality of Moroccan public financing made an IMF US$6.2 billion precautionary credit line unavoidable. The credit line was opened in August 2012, easing the pressure on foreign exchange levels. The IMF insisted on the need for a stricter control over spending and moving ahead with subsidy, retirement and tax reforms, but renewed the credit line in July 2013, signalling the credibility of Moroccan economic policy reform. The government had already reduced the oil subsidy burden the previous year in the midst of popular protests. This should have helped reduce the fiscal deficit to 5.5% of GDP in 2013. However, in August the central bank warned that the fiscal deficit had increased in the first half of 2013 and that fiscal and additional subsidy reforms were urgent.

In fact, subsidy reform was the origin of the government crisis that led to the resignation of five ministers during the summer, leaving the PJD alone to draw up the 2014 Loi de Finances (budget). The government wanted to apply the indexation of oil prices before summer, but the reform was postponed due to the resignation of Istiqlal ministers, then to the Ramadan and finally to the holidays. It entered into effect after the summer amidst popular protest but with the renewed opposition of the Istiqlal party, eager to reap the political benefits of its exit from the governmental coalition. In this complex political and economic context, the budgetary process was delayed and finally started at the end of September under very austere prospects and the worsening of economic growth forecasts for 2014.

The good news for Morocco is that it has avoided economic collapse under very difficult circumstances. While reserves remain scarce, IMF backing helped it come back to the market in December 2012 for the first time in two years, successfully issuing 10-year bonds at 275 bp over US Treasury yields. The 10-year component bond that reopened in May 2013 was priced lower, at 220 bp over US Treasuries. The government has also announced the issue of its first sukuk, a sharia-compliant bond targeting both Gulf demand and domestic public opinion. Moroccan private banks are also going back to the market, reflecting more stable financial conditions. The uncertainties regarding the eventual spill-over from the Arab Spring have not completely faded away, but have been greatly reduced. Morocco has not suffered from the disruption of economic activity that is still affecting Tunisia and Egypt, not to mention Libya and Syria. On the contrary, in the last few months it has benefited from trade, foreign investment and tourism diverted away from Tunisia and Egypt, its traditional competitors.

According to UN World Investment Report data, Morocco was the top recipient of foreign direct investment in North Africa in 2012, surpassing Egypt for the first time. According to STR Global, a firm that tracks the hotel market, Morocco had the highest growth in demand for hotel rooms in the Middle East and Africa in the year to May 2013. Regarding exports, the country has prepared a new export stimulus package to reinforce its strategy of diversifying its exports away from the stagnant EU markets towards more dynamic destinations. Since 2009, the EU’s share in Moroccan exports decreased from 66% to 57% in 2012, while the export share to the US rose from 3% to 4.3% and to Africa from 7.3% to 9.5%. In the coming months two significant projects aimed at serving the export market will come on stream, both in Tanger-Med: the Renault factory and a new oil bunkering facility.

The bad news for the PJD is that it will pay on its own most of the political cost of economic policy reform, which implies unpopular measures that can alienate its voters. Since corruption has not been eradicated, the government’s effectiveness has not improved and unemployment continues to rise (even if slightly), it is difficult to see how the PJD can retain the support of the average Moroccan voter with just the issue of sukuks and other religious gestures. Economic results will probably not match the party’s electoral pledges and non-economic results will hardly compensate for a de-legitimised economic management. The PJD risks having to learn the hard way the first lesson of policymaking according to the electoral cycle: maximising the chance of re-election requires restrictive policies to be applied in the first half of a government’s term in office and blaming them on the previous government, while expansionary policies should be restricted to the second half of its term and just prior to the next elections. The PJD has done precisely the opposite, but to be fair it should be recognised that in Morocco the art of managing electoral cycles is beyond the institutional ability of its political parties. Perhaps next time.