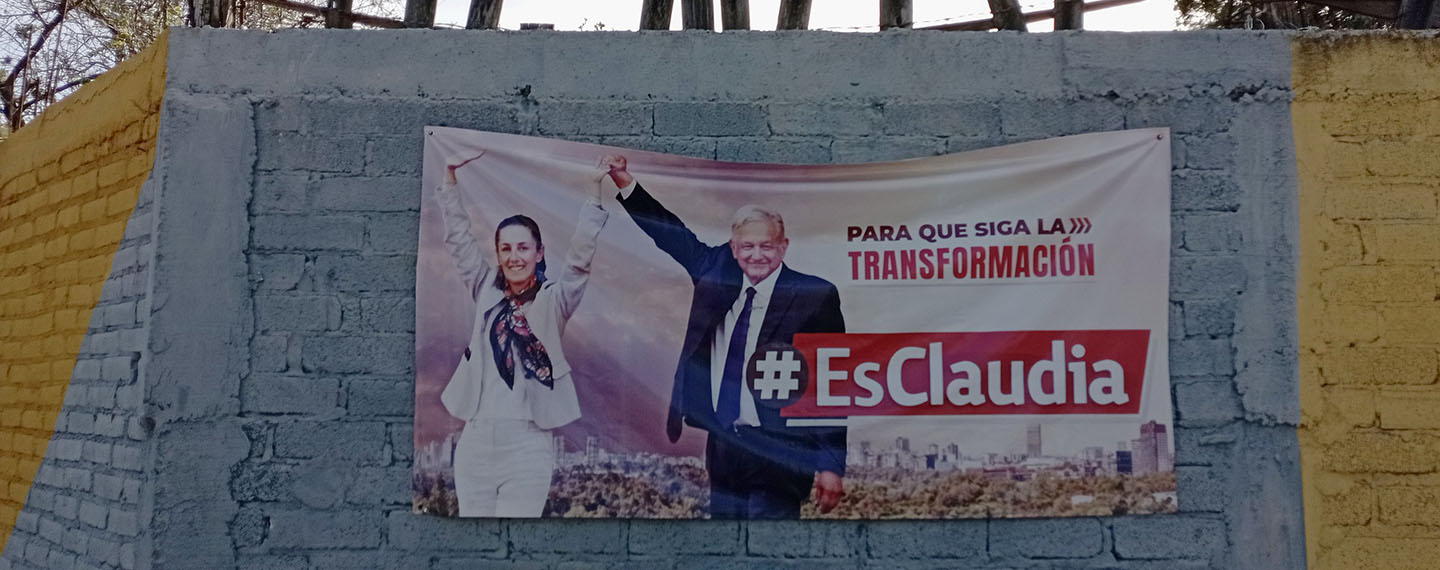

Few doubted that Claudia Sheinbaum, the hand-picked candidate of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, would win Mexico’s presidential election on 2 June. But similarly, few foresaw the scale of her victory. Not only did she win 59.8% of the popular vote but the ruling coalition also won the two-thirds majority of seats in the lower house of Congress required to change the constitution and ended just three short of a similar majority in the Senate. Sheinbaum will thus have a clear mandate –she won more votes and a higher percentage than López Obrador (or AMLO, as he is often known) did in 2018–.

The underlying question which Sheinbaum will soon have to answer is whether she wants to lead a social-democratic government or continue along the populist nationalist path followed by AMLO.

Should it wish to, the ruling coalition will not have much difficulty winning over the senators required to approve AMLO’s proposed constitutional amendments, which include the election of Supreme Court justices and the abolition of independent regulatory agencies. For Sheinbaum that is more of a problem than an opportunity. The prospect of constitutional change and untrammelled executive power triggered fears among investors that saw the peso plunge in value by 8% against the US dollar in the week after the election, its sharpest fall since the start of the pandemic in 2020. The underlying question which Sheinbaum will soon have to answer is whether she wants to lead a social-democratic government or continue along the populist nationalist path followed by AMLO.

Sheinbaum owes her victory almost wholly to AMLO, the most powerful president since Carlos Salinas de Gortari (1988-94). Salinas opened Mexico, a previously introverted country, to globalisation, negotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA or TLC). That opening was followed by democratisation: the victory in 2000 of Vicente Fox for the conservative National Action Party (PAN) ended seven decades of authoritarian rule by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). Parts of the Mexican economy have prospered and become deeply integrated with the US. But many Mexicans feel that they have not seen much benefit from globalisation or from liberal democracy. They form AMLO’s constituency. Like him or hate him, he is an extraordinarily effective politician, having travelled Mexico town by town several times. He has forged a deep bond with many ordinary Mexicans. As president he has almost doubled the minimum wage and expanded cash benefits for poorer Mexicans. Poverty fell by 7% according to official statistics.

On paper, the opposition had an effective candidate in Xochitl Gálvez, a self-made entrepreneur and independent politician of partly indigenous descent. But she was burdened by the discredit of the parties in her coalition (principally the PAN and the PRI). Ultimately, she disappointed, winning only 27%. Movimiento Ciudadano, a newish centre-left party, won 10.3% and would appear to have a future. Sheinbaum made no big mistakes and grew in confidence on the campaign trail. Her victory is historic, the first woman to be elected president in a country that is almost synonymous with machismo.

AMLO has insisted that he will retire, saying of Sheinbaum ‘will try not to bother her’ (‘voy a procurar no molestarla’). She will hope he sticks to his promise. Mexico cannot be governed by a puppet. Sheinbaum has been publicly loyal to AMLO. But her political origins are different to his. He cut his political teeth in the PRI as a supporter of Luis Echeverría, a leftist-populist president (1968-76). He is above all a nationalist who believes in state control of energy. She comes from the hard left associated with the National University (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) She combined political activism with an academic career as a scientist. She is a feminist and a proponent of green energy. While he is a communicator who sets the political agenda with his rambling morning press conferences (‘las mañaneras’), as governor of Mexico City for the past six years she portrayed herself as a technocrat and policy wonk. She says she wants to expand social provision, improve health care while encouraging private business and investment –a seemingly social-democratic agenda–.

Her first and perhaps biggest challenge will be managing her relationship with AMLO, and with Morena, the faction-ridden party that he created. Others include the economy, fiscal and energy policy; crime and insecurity; and relations with the US. Take the economy: partly thanks to the pandemic, income per person has barely grown under AMLO. With lower costs and almost seamless access to the US market, Mexico is uniquely well-placed to take advantage of ‘nearshoring’. Yet not much of this has happened. Nearly all the foreign direct investment Mexico has received recently has come from companies already established there, not new arrivals. Investors complain that Mexico cannot provide the cheap energy, reliable water supply and security that they need. That is partly because AMLO pursued a nationalist and statist energy policy, pouring public money into Pemex, the grossly inefficient state oil and gas company, and largely reversing a reform that allowed private investment in energy.

AMLO’s macroeconomic policy was generally orthodox, involving fiscal austerity (he cares about the stability of the peso). But public spending ballooned ahead of the election. The fiscal deficit is forecast to reach 5.9% of GDP this year, the highest figure since the 1980s. Sheinbaum has ruled out immediate tax increases. But to fulfil her promises, she will need to raise taxes and/or slash transfers to Pemex.

The second big challenge is organised crime. The murder rate has climbed to 23 per 100,000 and large swathes of rural and small-town Mexico are under the de facto control of crime gangs. In Mexico City Sheinbaum cut murders by strengthening the police, giving them investigative powers, installing tens of thousands of security cameras and investing in educational facilities and community centres for young people. It will not be easy to scale up these policies nationally, as she proposes.

Mexico’s next government may have Donald Trump as a neighbour. He is likely to press even harder than Joe Biden for Mexico to control migration and the export of drugs, especially fentanyl. Sheinbaum says she wants ‘a very good relationship’ with the US. She faces a possibly difficult renegotiation of the USMCA (US, Mexico and Canada Trade Agreement), Trump’s replacement for NAFTA, in 2026 in which the US may press to stop Chinese companies using Mexico as a base to export northwards.

But the biggest headache of Sheinbaum’s presidency may come even before it starts. The new Congress is installed on 1 September, a month before the presidential handover. AMLO wants to use this period to ram through his constitutional proposals, which include big pension increases, the formal transfer of the national guard to the armed forces, as well as the abolition of legally independent regulators of telecoms, energy, competition policy and freedom of information. His plan for the election of supreme-court justices –only Bolivia does this– seems aimed at guaranteeing political control of the judiciary. Taken together with his plan for the direct election of the electoral authority, in the view of critics these changes would abolish the checks on absolute executive power which are at the heart of liberal democracy.

These proposals risk embroiling Sheinbaum’s presidency right from the outset in economic turbulence and political confrontation. She has called for a wide public debate on judicial reform, which could offer a way to water it down. In victory, she was conciliatory, promising to listen to opponents. Many friends of Mexico will hope she does.