Every four years, the US National Intelligence Council (NIC) carries out an exercise of the utmost interest looking at world trends. This is the sixth report in the series, and it has been published on the eve of Donald Trump’s arrival in the White House this Friday, a man whose policies, unknown as they may be, will impinge on the world. But the NIC tries to look further, five to 20 years ahead. The first conclusion will not go down well with the President of the most powerful country on earth (although Obama had assimilated it): he is no longer so all-powerful, and even the West could, if not break apart, then at least become inward-looking, something that will lead countries like China and Russia to challenge the superpower and the world order it has led since the end of the Second World War and the Cold War.

This time the global trends study is titled ‘The Paradox of Progress’. The paradox is the fact that the advances of the industrial and information ages, the same trends that form the basis of this report, are leading to a world that is simultaneously more dangerous and richer with opportunities than ever before. The progress made in recent decades has been unprecedented in terms of the connectivity between people and the lifting of thousands of millions of people from poverty. But it also led to the economic crisis of 2008, the Great Recession, the thwarted Arab Springs and the global flourishing of populism.

Seven global trends over the next 20 years are identified, all of them bearing consequences: (1) the rich countries (including China) are ageing, but not the poor ones; (2) the world’s economy is heading for slower growth, something that threatens poverty reduction in developing economies; (3) technology will hasten progress, but cause discontinuities; (4) ideas and identities are generating a wave of exclusion; (5) governing is getting harder; (6) the nature of conflict is changing with the divergence of interests between major powers, the expansion of the threat of terrorism and another series of issues; and (7) climate change and healthcare issues will require greater attention. ‘These trends’, the report concludes, ‘will converge at an unprecedented pace to make governing and cooperation harder and to change the nature of power – fundamentally altering the global landscape’.

States, however, will continue to be important, provided that they manage to bolster their resilience through governance, the economy, the social system, infrastructure, security and geography and the environment, even though they will be challenged by non-state actors. But the most powerful players of the future will be those states and groups ‘who can leverage material capabilities, relationships and information in a more rapid, integrated, and adaptive mode than in generations past’. What will count, in other words, is the mastery of technology and its application, as we are already seeing.

Over the shorter term, five years hence, these global trends will lead to greater volatility, among all regions and types of government, both between and within countries, placing the international order in question. Its net effect will be ‘greater global disorder and considerable questions about the rules, institutions and distribution of power in the international system’. And it is a landscape in which the foreseen ‘hobbled Europe’ will serve for little.

It is an exercise that differs in both its approach and its conclusions from that of the World Economic Forum (WEF) and its 2017 Global Risks Report, which identifies as the top five risks, in this order: (1) weapons of mass destruction (the only geopolitical risk); (2) extreme weather events; (3) water crises; (4) major natural disasters; and (5) the failure of climate change mitigation and adaptation. It identifies various challenges that will need to be addressed in the years ahead, among them those of: (1) reforming market capitalism and combating inequality, which it sees as one of the great dangers; (2) addressing the importance of identity and community; (3) managing technological change and the Fourth Industrial Revolution; and (4) protecting and strengthening our systems of global cooperation, as well as reinforcing democracies in crisis. In other words, that the weather may impinge more than terrorism.

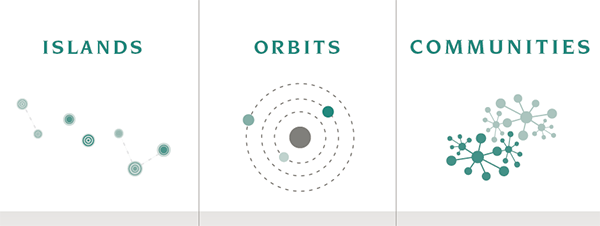

Further into the future, around 2035, the NIC foresees three great narratives or scenarios: that the world becomes divided into islands, into orbits or that it organises itself into communities. By ‘islands’ it means a restructuring of the global economy, leading to long periods of negligible or zero economic growth, and an abandonment of the idea of ongoing globalisation, a globalisation that, as the report points out, has ‘hollowed out’ the middle classes in the West, with a reduced capacity of governments to meet the demands of their societies and greater protectionism.

The ‘orbits’ idea refers to competition between major powers in search of their own spheres of influence, while they try to maintain their internal stability, in reference essentially to China and Russia, but also a general growth of nationalism. From there it is possible to head towards peace or, on the contrary, to serious conflicts. If this scenario prevails it will mean that national interests predominate over international law (which, it must be said, has not advanced over recent decades).

The ‘communities’ option involves states losing power to local administrations and private or non-state actors who, particularly by harnessing information and communication technologies, will throw into question what is traditionally understood as governance.

As with all such exercises, the options may be combined. In the face of them, ‘the most resilient societies will also be those that unleash the full potential of individuals – including women and minorities – to create and cooperate’. Will Trump have read this already long report in a classified version, despite his mistrust of the intelligence services? He and his team will have to face, and avoid creating, many dangers, threats and risks. But they may also be in a position to help to deactivate them, or at least not aggravate them. Be that as it may, not everything, but a great deal, remains to be determined. Indeed, as the NIC points out, whether the world improves or deteriorates will depend on our own decisions as human beings.