As COVID-19 started to hit the country hard, on 14 March 2020 the Spanish government declared a state of alarm (Article 116 of the Constitution contemplates three states of response to crises: alarm, emergency and siege, in ascending order) and confined its population . Residents were obliged to stay at home unless they needed to go to a hospital, a supermarket, a pharmacy or work in essential economic sectors. Schools were closed and online work was encouraged in all business activities, while the retail and hospitality sectors were completely closed down and, for the first time ever (something that had not even occurred during the Civil War), bars were shut. Tourism had gone; dystopia was upon us.

Some days later I received a call from the Spanish government and was asked to join a small group whose task would be to design a lockdown exit route. Those were difficult days: on 15 March the death toll was for the first time above 100 per day (in fact, 152), on 24 March the country recorded 500 deaths (at 514) and on 2 April the rate reached a high of 950 deaths. The headlines in the newspapers were frightening: Spain was losing 1,000 people a day; it felt like wartime.

By then our work, carried out in confidentiality and away from the media spotlight, was well under way. Naturally, the team was multidisciplinary , including not only epidemiologists, microbiologists and virologists, but also experts in infectious diseases and public health, and medical statisticians. In addition, there were economists, political scientists, sociologists, diplomats, philosophers, engineers and new technology and law experts. The complexity of the task was immense (it had never been done before), so counting on different perspectives was essential. My own task was to focus on anything related to international and comparative political economy.

Very soon one of the first political-economy questions to arise was precisely how to deal with the tension between the priority of the epidemiologists –to continue with the lockdown until the virus was under control– and that of the economists –to reignite the economy as soon as possible–. After intense debates we agreed that while these two realms could not be seen separately, since, indeed, they are strongly intertwined –the economy cannot function if the population is not healthy, and people cannot be healthy in the long run if the economy collapses–, the epidemiologists should have the primacy.

Where there was a strong consensus between the epidemiologists and the economists, however, was in agreeing that geographical asymmetry would be inevitable in lifting the lockdown.

The course of the epidemic was uneven in different parts of the country, so it made sense to have stricter lockdown and social-distancing measures in the areas that were hardest hit, while they should be started to be eased in those less affected, so that economic activity could resume earlier.

That is why, when the French President Emmanuel Macron announced on 13 April that France would start lifting its lockdown on 11 May, we received the news with scepticism. As one of the medics told us at a discussion, ‘those that speak about dates do not know much about viruses’. But the reality was that very quickly everyone became obsessed with dates. The business community was becoming particularly restless, noting that other countries were already putting dates to their exit strategies. The pressure on the Spanish government was mounting and we felt it.

What was our counter-proposal? First, we realised early on that there was no blueprint for a successful exit. China was the only empirical case that we could study. It had shown that dividing the country into geographical units to choke the spread of COVID-19 was effective. But its units were small (districts) and based on very intrusive ‘neighbourhood patrol teams’ that would be unacceptable in a democracy like Spain. The experiences of ‘testing, tracing and isolating’ in countries such as South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore were far more instructive.

Taking all of this into consideration, after four weeks of comparative studies and analysing the situation of the virus in Spain, and what was needed to combat it, and following numerous debates and meetings with members of the government, we finally came up with a plan based on four pillars: (1) proper data and healthcare capacities; (2) geographical asymmetry; (3) a two-way street with different speeds; and (4) subsidiarity and co-responsibility.

The first pillar is the most important. It hinges on generating the right data. For instance, about when the first symptoms appeared in each patient, his contacts, when he was hospitalised, how many beds were free in his hospital, the saturation level of the ICUs in his particular hospital on entering, and the date of discharge. We realised that the information was not complete and rapidly became aware that this was a problem in other European countries too, including Germany, which was coping with the crisis relatively better (I would like to use this opportunity to express my gratitude to our counterparts in similar task forces during those intense and dramatic weeks: many frustrations were shared and useful information was exchanged).

Hence, the first pillar is based on precisely this: the capacity to test, trace and isolate (potential) cases and to have the strategic healthcare infrastructure to deal with a possible new outbreak. In other words, the minimum number of beds and ICUs empty and ready to be used, but also enough resources and staff in primary care to detect and trace potential cases as soon as possible, and even the use of new technologies like apps, with a pilot project starting soon in the Canary Islands.

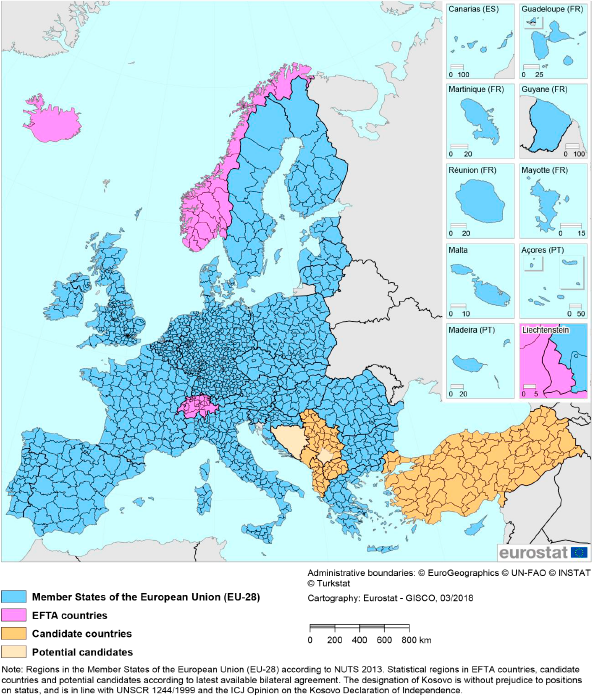

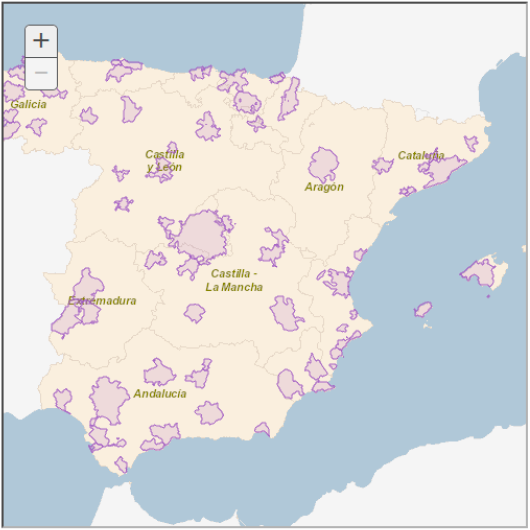

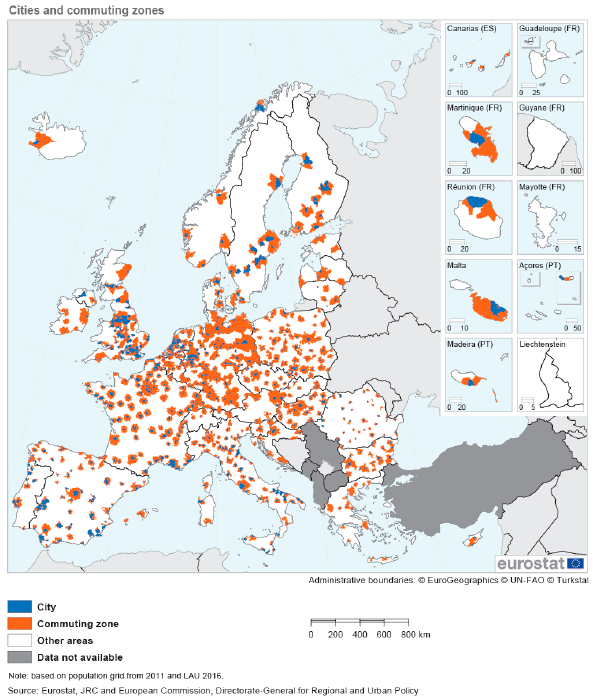

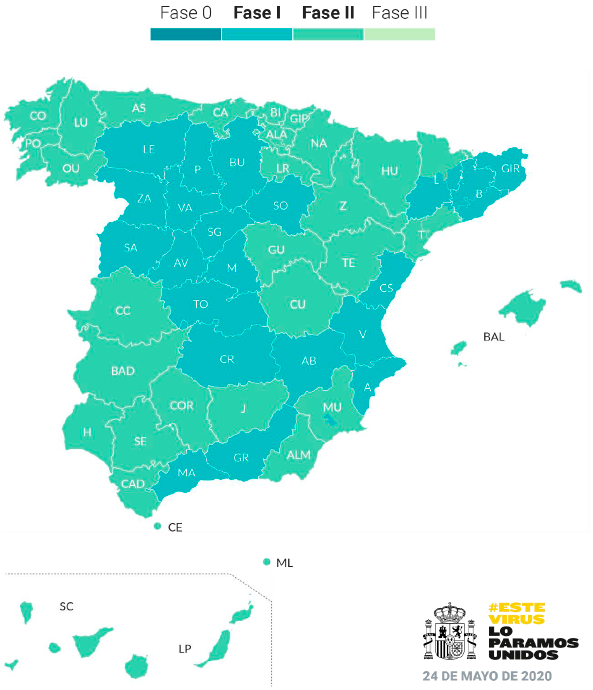

The second pillar is geographical asymmetry in lifting the lockdown. Here we agreed that the municipal level was too small. Many people live and work in different municipalities, hence closing them off would be too disruptive. Spain’s Autonomous Communities (regions), on the other hand, were too big. Imagine, for instance, that Almería were to have very few cases and Sevilla many. Why would Almería need to wait to open up until Sevilla improved? So we opted for the province, which is an administrative layer in between the region and the municipality (NUTS3 in the European Commission regional map, see Figure 1) and roughly coincides with the functional urban areas (cities and commuting zones, as identified by Eurostat, see Figures 2 and 3 below), covering 70% of Spain’s population.

The Spanish Government has broadly applied this scheme, although certain regions have opted for sanitary areas, instead of provinces, to accommodate the diverse geographical idiosyncrasies such as the difference between urban and rural areas, where population density is lower and therefore restrictions can be milder (see Figure 3).

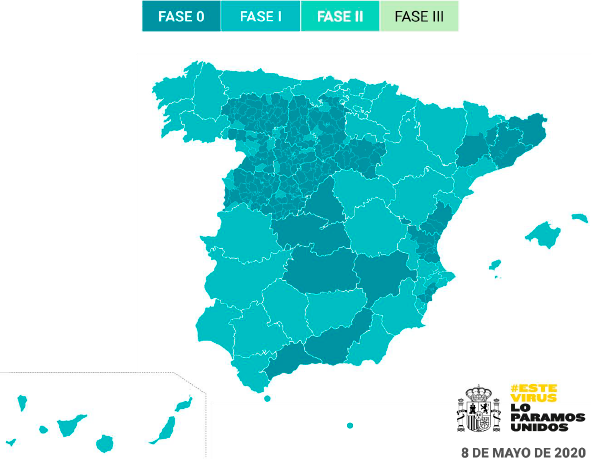

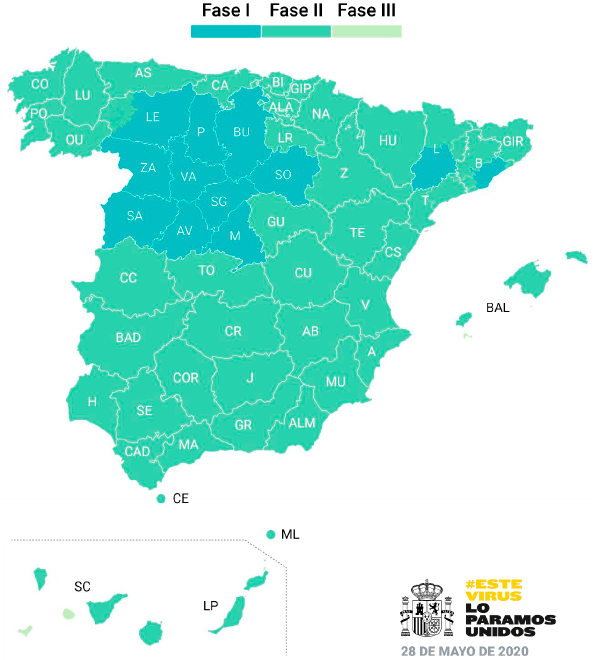

This leads to the third pillar. The lifting of the lockdown has been divided into four phases: one preparation phase and three exit phases. Phase 1 started for half of the country on 11 May, and two weeks later (25 May) this half moved to phase 2, while the rest of the country moved to phase 1 (see Figures 4 and 5 below). Every phase has different restrictions. For example, in the preparation phase, bars and restaurants were closed and there were to be no social gatherings. In phase 1, however, bars can admit customers if they have outside tables, and there can be social gatherings of up to 10 people, while retail shops can open 400 square metres of commercial space. In phase 2 bars and restaurants can open their indoor facilities, social gatherings can rise to 15 people, retail shops have no space restrictions and theatres and cinemas start operating with limited admissions and subject to social distancing.

Of course, this gradual and asymmetric approach has been politically controversial. Every province and every region want to move to the next phase as soon as possible, but it was important to assimilate the notion that the generation of capacities is fundamental and that we need to learn to live with the virus gradually and with precautions. The Region of Valencia first complained that it could not pass from the preparation phase to phase 1 on 11 May and later, after seeing a spike in new cases, it decided to wait to move on to phase 2 for another week in order to have the situation better under control, only progressing to that stage on 1 June (see Figures 4, 5 and 6 below to see the gradual change in the map). Indeed, the plan is designed to move forward, but if the virus again gains strength, certain geographical units might need to move backwards to a previous phase. This is a two-way street, with, it is hoped, most traffic moving forwards, although setbacks may occur and U-turns might be necessary.

For all of this to work, however, it is necessary to count on the cooperation of regional and local administrations. The subsidiarity principle is a key factor. For instance, it is not the job of the central government to decide how social distancing should be applied in the country’s 3,000 beaches, since that is the task of local municipalities. The police cannot check whether the maximum number of people (and the two-metre social distancing) is respected in social gatherings at home. That is the responsibility of each citizen. Co-governance and civil discipline are therefore indispensable.

At present, moving between provinces or sanitary areas (in the regions that have applied such a division) is banned. In principle this should last until phase 3 is completed and Spain enters a ‘new normal’. But if the minority government is unable to renew the state of alarm (requiring Spanish parliamentary approval every two weeks) there should be other co-governance and co-responsibility schemes agreed upon by the regions and the central government to maintain the plan’s (sound) logic.

In terms of dates, the initial idea was to move from phase to phase every two weeks, a reasonable time frame to assess the course of the pandemic. This would mean that the geographical units that moved to phase 2 on 25 May would be in the green zone (the new normal) by 22 June and places like Madrid and Barcelona, which have a two-week lag, would be there only on 6 July. But the government has already announced that it wants to open up the country to European tourism on 1 July, so it is likely that opening up might accelerate if the epidemiological situation continues to improve (see Figure 7).

Nonetheless, as mentioned above, although the speed might be accelerated because the economic pressure to open up is beginning to be huge, it would be good to keep the plan’s basic framework in mind, even if only in the background, because there may be a few bumps on the road to achieving a treatment, vaccine or herd immunity, and we might have to slow down, stop or even turn back temporarily. Of course, if most people respect social distancing (the widespread use of masks in Spain is encouraging) that is less likely. One can design the best plan, but if people fail to adjust to it, effectiveness will be undermined.

This also means that the plan needs to be flexible. The central government needs to listen to regional and local authorities and to key social actors in business and civil society in order to improve the plan. In this respect, some recent rectifications and improvements are also encouraging. We are in uncharted waters and, as Paul Collier has pointed out , experimentation, trial and error, and best-practices are the best way to fight COVID-19. And this is applicable to both Spain and the rest of Europe. Exit strategies have been different in each EU country and that is not bad per se (it might even be positive, since we can learn from each other) but now is also the time to think how we can cooperate to make them compatible so as to re-start social mobility in the EU in the safest possible way.