In recent years the production of oil in Libya has endured a rollercoaster ride reflecting a succession of blockades, attacks, strikes and sabotage carried out on oil and gas installations (some accounts catalogue up to 75 incidents and dozens of fatalities). Output in 2010 was close to 1.6 million barrels per day (b/d) but fell to 500,000 in 2011, only to recover to nearly 1.4 million and subsequently to fall again below 400,000 barrels in 2015. The decline in the oil price and the problems in restoring the level of exports are causing Libya’s economy and current accounts to haemorrhage. The public deficit for 2015 looks likely to exceed 40% of GDP, and the IMF believes that if the situation does not improve it may approach 70% of GDP in 2016. Fiscal imbalances of this magnitude are unheard-of in modern economic history. Although the country benefits from two major buffers –its reserves of foreign currency and the assets of its sovereign wealth fund– the former are in freefall and both have been subjected to the tug of war between the two Libyan governments. It has been months since the central bank published any data regarding the levels of its currency reserves, something that has caused widespread alarm, despite the reassuring messages both it and the IMF have been sending out to the effect that the country still has reserves to last several months, and even two to three years.

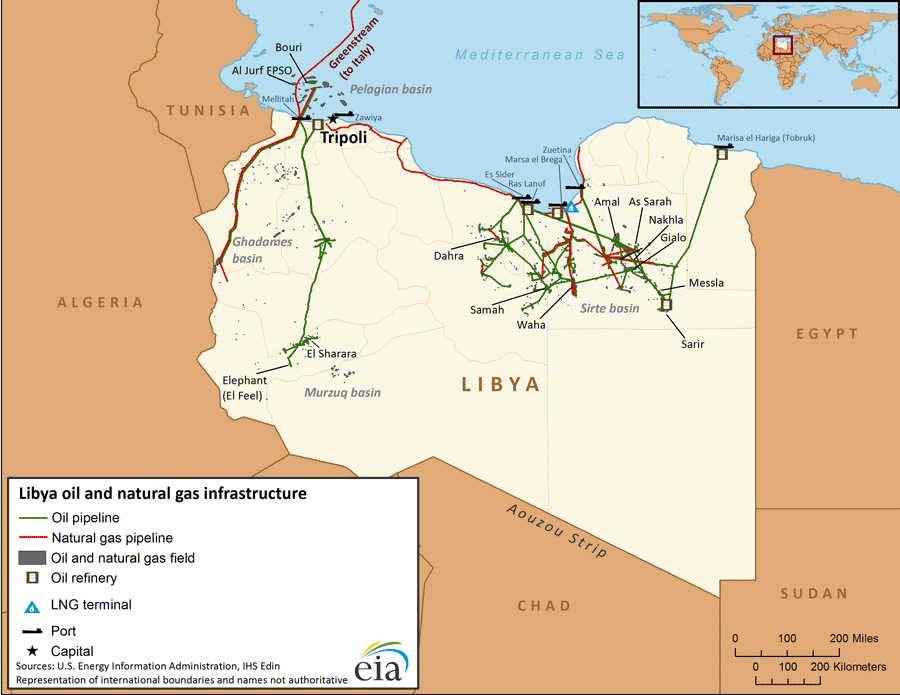

But the struggle to control the assets of the central bank and the sovereign wealth fund are nothing but the backdrop to a more explicit fight over oil revenues, which manifests itself in the tug of war for the state oil company and its subsidiaries and for control of the energy infrastructure (fields and export terminals). In 2011 we argued that Libya’s energy priorities consisted of security, reconstruction and governance, and we warned that the conflict could degenerate into a struggle over resources, as indeed has transpired. The nature of this conflict is extremely complex, with political, territorial, ethnic and tribal divisions that share only the political economy giving access to Libya’s hydrocarbon resources. So extreme did the situation become that the security organisation responsible for protecting the installations wrested control of them to extract political and economic advantages, and the US had to intercept the oil tanker Morning Star to prevent it being illegally sold by the government in the East.

The difficulties in forming a unity government show the hurdles that lie in the way of creating a pattern of governance for these resources that is acceptable to all sides in the conflict.

The emergence of ISIS, with recent attacks on various installations, aggravates the problem and raises the question of whether this terrorist organisation wants to replicate the strategy used in Iraq and Syria, where it derives significant income from the sale of oil, now in decline after the aerial attacks on its facilities. For the time being it seems that the attacks have focused on the destruction of targets to undermine the two governments economically as they inch towards unity, and possibly on the theft of fuel for replenishment purposes or to sell on the contraband markets that have existed for some years. It is estimated that more than half the fuel sold in Libya at subsidised prices ends up in those neighbouring countries where the prices are much higher (which is all of them except Algeria). Conditions in Libya are not, however, as conducive to contraband as those in Syria and Iraq, where the smuggling networks are much more consolidated and benefit from numerous local and Turkish intermediaries. Nor has the Syrian phenomenon of backyard refineries taken hold in Libya, because the population density is much lower, the penetration of ISIS has been relatively limited and the main oilfields are located a long way from the inhabited areas on the coast and the contraband networks on the borders. However, the news that ISIS is seeking engineers and former workers in the Libyan energy industry, out of work due to the closure of the majority of the installations and the departure of large international companies, could indicate a change of strategy.

The international community has limited room for manoeuvre for tackling the struggle to control resources and the ISIS offensive. As far as the former is concerned, it has shown a firm commitment to respecting the integrity of the state oil company and contracts signed with western oil companies, as well as that of the central bank and the sovereign wealth fund, and not allowing sales of crude by other players, including sales supported by the government it recognises as legitimate. This stance, although difficult to account for politically, should be maintained to avoid the collapse of the only institutions still deserving that name in Libya. By contrast, measures such as embargoes, asset freezes and/or the creation of accounts controlled by the international community to manage Libyan oil income are highly problematic. They would involve the de facto curtailment of Libyan sovereignty and necessitate the taking of highly risky direct decisions on expenditure, and even contending with corruption. The magnitude of the responsibility seems as great as the capacity to manage the payments is inadequate, apart from the fact that nobody at the United Nations wants to repeat the fiasco of the Iraqi food-for-oil programme.

The unity government seems to be the only way forward, but political interests should not be allowed to obscure the economic urgency of restoring oil exports, enabling the Libyan economy to return to viability. As the International Crisis Group has warned, if the central bank’s payments to the militias collapse it could plunge the country into even greater chaos, affecting state employees and vital exports alike, and offering new opportunities to ISIS. Only correct governance of Libyan hydrocarbons and their revenues, one that addresses not only the distribution of income among factions but also a transparent and effective model designed to benefit the Libyan populace as a whole can ensure the long-term stability of the country and its energy industry. In the short term, the international community continues to lament the lack of alternatives to prevent ISIS from destroying the country’s energy infrastructure, when it should have already started concerning itself with the qualitative leap that would be involved in a change in strategy, including taking control of such resources and coming up with new channels of finance and means for exerting power. This would appear to be more difficult in Libya than in Syria, but the volatility of the country does not enable more adverse scenarios to be entirely ruled out.