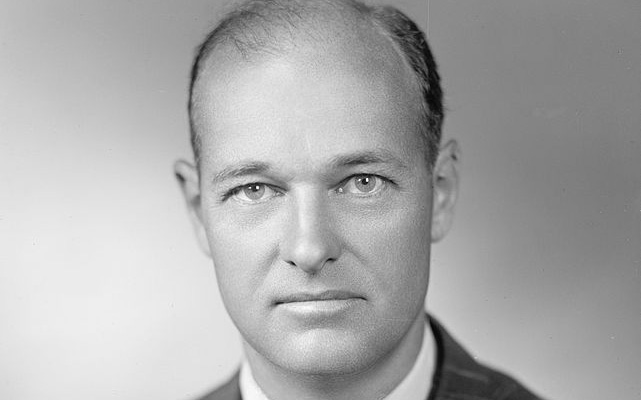

On 22 February 1946 George F. Kennan, chargé d’affaires at the US embassy in Moscow, sent Washington a memorandum known as the ‘long telegram’, which was 5,000 words in length. A recapitulation of this document, The Sources of Soviet Conduct, written by the selfsame Kennan under the pseudonym of ‘X’, subsequently appeared in the journal Foreign Affairs in 1947. This was a landmark in the history of international relations and established the reputation of its author as one of the main US representatives of political realism. But the reflections contained in what follows do not seek to present a historical analysis. They seek to delve deeper, with resonances from the past and present, by revisiting some of the opinions of that great proponent of the policy of containment. With what would George Kennan, having the traits of a poet in the way he analysed reality, furnish a world in which there is no longer a superpower of the USSR’s ilk, an unstable world where nationalism and radical populism are trying to establish themselves?

The fundamental thesis of The Sources of Soviet Conduct is that the USSR’s foreign policy was determined by ideology and by circumstances. The only thing that seemed to matter to Kennan’s contemporaries was the international spread of communism. In this regard he harboured a loathing for McCarthyism, above all on account of its anti-intellectual bent. For he had no time for broad-brush analyses such as the Truman Doctrine, which seemed to perceive communism as a coherent, unified and self-aware body of thought. The simplistic brand of anti-communism failed to realise that its opponent was no more than a ragbag of vaguely-defined, obsolete and contradictory theories. Soviet communism lacked the high degree of coordination that was ascribed to it. Hence, like De Gaulle, Kennan preferred to separate what was Russian from what was Soviet. He sensed the rifts between the USSR and China and other communist countries. Overcoming ideological differences, the day would come when the US would open diplomatic channels with these countries.

One of the things Kennan bequeathed to us in his celebrated ‘long telegram’ remains valid in perpetuity: our enemies are humans too. We have seen this recently in Bridge of Spies, that remarkable film by Steven Spielberg. The Soviet leaders were the heirs of Marxist-Leninism, but there is no point searching that ideology, or any other of a radical stripe, for a user’s manual, unless one has allowed oneself to be blinded by the propaganda. Rather, the leaders manoeuvred in accordance with the circumstances, which were necessarily in flux. There is scope therefore for pragmatism in all manner of messianic programmes, and especially in communism. Stalin and the majority of his successors were undoubtedly pragmatists.

On the basis of such thoughts we might arrive at the conclusion reached by Kennan: in the study of international relations it is not enough to have a knowledge of history, or of political theories, or even of international or domestic judicial systems. Nor should the international analyst be altogether unfamiliar with certain notions of psychology, albeit somewhat sketchy. This is what enabled Kennan to emphasise that the Soviet leaders –and, I would dare to add, all leaders with social engineering in their souls– presumed to understand human nature better than anyone. Psychology was something that also interested Keenan, possibly based on his reading of Clausewitz, that forerunner of psychological warfare, but also as a great admirer of Russian culture: he might have reminded analysts of their limitations by citing that aphorism, sometimes used by Turgenev, according to which ‘the human soul is shrouded in darkness’. In any event, Kennan believed that reading the classics made an excellent travelling companion to diplomacy, especially the Bible, Plutarch, Shakespeare and Gibbon, where ‘the most subtle and revealing expressions of human nature’ were to be found.

Kennan emphasised that Stalin’s radicalism set him apart from the culture of compromise that is characteristic above all of the English-speaking democracies. A radical in a position of power will rarely yield on any point because it entails the risk that the regime, and with it his personal power, will collapse. The messianic features of a secular religion are accentuated when its leader is simultaneously its king, prophet and lawmaker. In the year that the ‘long telegram’ was written, Stalin had vanquished all his rivals, although Kennan never tired of pointing out that internal power struggles are the main enemy of totalitarianism of any stripe. And to forestall the leaders’ authority being questioned, they often resort to the myth of foreign conspiracies, which serves as a justification for unlimited internal power imposed with iron discipline.

What Kennan prescribed for the US in the ‘long telegram’ was ‘intelligent long-range policies’. This translated into containment, the policy of containing Russia’s expansive tendencies, always over the ‘long-term, patient but firm and vigilant’. Were there grounds then for harbouring any hope? Kennan was confident that young people would be dissatisfied with precarious economic development, and it was in fact just such economic shortcomings that ensured that the USSR was unable to defeat poverty. There would come a time when the inability of the Soviet system to export successes or show real evidence that it had obtained material prosperity for its citizens would be laid bare. Four decades later events proved Kennan right. However, the journalist Walter Lippmann criticised a strategy that was largely founded on patience on the grounds that it handed Stalin the initiative.

But the patience of containment has no connection with the illusory hopes of conclusive victory. Kennan was the sworn enemy of any doctrinaire absolutism, no doubt because he had a yearning for the diplomacy of the 18th century prior to the devastating Napoleonic Wars. Total victory, with harsh conditions for the defeated, could only lead to a much worse conflict. This accounts for Kennan’s admiration for the 19th-century Swiss strategist, Antoine-Henri Jomini, who argued that the fundamental problem of war was to give the enemy two options: to retreat, or to fight in unfavourable circumstances. In the last years of his life, at the age of almost 100, the father of the containment theory showed no enthusiasm either for the expansion of NATO or for the military interventions in Kosovo, Afghanistan or Iraq. His readings in history alerted him to the illusion involved in rapid victories obtained through technological domination. And the same readings helped him become better acquainted with the lessons of the past before taking steps into the future. After reading Gibbon he was fond of pointing out that occupying the territory of the defeated engendered the spirit of resistance on the part of the subjected populace. He was thus no advocate of unconditional surrender. It was necessary to punish leaders, but not to destroy a country’s administration, as represented by former members of the governing party, keeping in mind the need to avoid future social upheavals. A certain degree of stability was needed to preserve order. What happened in Iraq to Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist party has undoubtedly shown Kennan to be right.