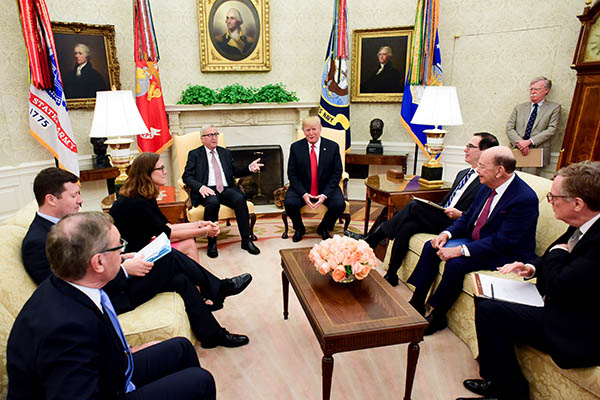

The US and the EU have decided to end their trade war, at least for the moment. After a meeting in Washington on 25 July, the President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, and the US President, Donald Trump, committed themselves to working together to create a transatlantic free-trade zone that would have no tariffs, subsidies or non-tariff barriers (although it would exclude the automobile sector). To begin with –although it is not at all clear how this will be achieved– the US will export more liquified natural gas to the EU (which would lower EU energy dependence on Russia) and the EU countries will buy more US agricultural produce (especially soy bean products). They will also begin to back away from the mutual tariff escalation that began a few months ago when the US imposed tariffs on European steel and aluminium imports, alleging (absurdly) reasons of national security and provoking a proportional response of reprisal tariffs from the EU. Therefore, while the negotiations remain underway, no new tariffs will be established (the US had promised to impose new tariffs on EU automobiles) and the two sides will work to eliminate the tariffs that have recently been approved. Finally, both powers will study together a possible reform of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) that would allow it to once again play an arbiter’s role in the governance of globalisation that, in recent years, it had been denied by the US.

“If Trump’s aim is to eliminate transatlantic tariffs he could have avoided this last year of rising trade tension”

In short, after months of playing a game of ‘who blinks first’ –which turned into a dangerous tariff escalation with no end in sight and that, in addition, undermined the confidence of both sides–, the US and the EU have decided to wind down the tension and search for a negotiated solution. This is good news for everyone. So, neither ‘trade wars are good and easy to win’ nor ‘tariffs are great’ (according to Trump via Twitter). The global economy had much to lose if the situation was not resolved soon. Although the trade war would not have generated a recession by itself (and its effects would have been fully felt only over the medium to long terms), escalation of the conflict dangerously threatened to destroy the WTO’s multilateral system of rules that has underpinned the liberal international order and a large part of the prosperity generated in recent decades (even if its distribution has remained overly unequal). Furthermore, the dynamic of confrontation also threatened to generate an irreversible breach in the transatlantic relationship, clearly visible both at the latest G7 Summit in Canada and at the summit meeting of the Atlantic Alliance in Brussels.

Nevertheless, things have not returned to normal. First, Trump continues to be an unpredictable nationalist whose word is worth very little. To the extent that this decision allows him to sell to his electorate the notion that he has forced the EU to bend to his will with his impressive negotiating skills, then Trump will be true to his word. But if that does not work, or becomes unnecessary, he could easily change his mind, especially when he sees that the US current account deficit does not decline (and it will not as long as the country continues to reduce taxes and undermine the national saving rate) or that German exports to the US remain strong due to the Americans’ inclination to continue buying top-of-the-range German cars.

Secondly, what has really happened with all this is that we have simply returned to the negotiation agenda of the forgotten TTIP, the trade and investment treaty between the US and the EU (under negotiation since 2013 but abandoned by the Trump Administration in 2017). If Trump’s aim is to eliminate transatlantic tariffs he could have avoided this last year of rising trade tension. The TTIP already incorporated a negotiated reduction of practically all manufactured goods tariffs between the US and the EU. The negotiations had also agreed upon an increase in the LNG trade as well as a deeper convergence between transatlantic regulatory standards. On the other hand, the TTIP had already got bogged down over the harmonisation or mutual recognition of the rules governing both markets (essential for facilitating transatlantic trade in services). The treaty had also run into substantial resistance generated by the different regulatory traditions in respect to the precautionary principle, consumer protection, food security and financial regulation, among other areas. The TTIP had also been strongly opposed both by Europe’s citizens (because it would establish an investment arbitration mechanism championed by the US) and by the US authorities (who have not countenanced the idea of opening their lucrative public procurement markets to European companies). Given that neither of these stumbling blocks will be resolved soon (in fact, the opposition to Trump in Europe will make an ambitious transatlantic trade accord that much more difficult to achieve), the best case scenario might produce a light TTIP (focused on the full elimination of tariffs), the benefits of which we could already have been enjoying for the past two years if we had wanted that version of the treaty. But because Trump likes to seem the great negotiator who resolves problems he must first generate a false conflict where none existed before so that later he can give the impression that he has resolved it, when actually he has done nothing more than pull back his position, and always with an intimidating attitude and a disdain for the rules which allow international affairs to be something more than a minefield.

Beyond the need to bring the current trade war to an end, it is now paramount for the US and the EU to work with Japan and other like-minded powers to adapt the international trade rules of the WTO to the current economic reality in a way that can integrate China within the governance of globalisation without having to fight a trade war with it. This is the major challenge that we face and the most difficult. But it is good news that Trump treated Juncker as an equal and has understood that the EU is the key trade partner of the US.