The most recent jihadist mobilisation seen since 2012 across countries belonging to the EU is related to the ongoing like-minded insurgencies in Syria and in Iraq. However, the levels of this jihadist mobilisation, from all accounts in a receding sequence throughout last year, reached unprecedented peaks inside the EU. Since al-Qaeda’s creation in 1988 and the subsequent development of global jihadism as a worldwide movement, no other jihadist mobilisations –in connection, for instance, with conflicts such as those which took place in Bosnia, Chechnya, Afghanistan, Iraq between 2003 and 2007, Somalia or northern Mali– have risen to similar heights within the EU.

In order to explore and understand both the extent and scope of this most recent jihadist mobilisation affecting EU nations, it seems reasonable to rely on data about foreign terrorist fighters as a good indicator. It has been empirically established, precisely with respect to previous jihadist mobilisations, that individuals who radicalise as jihadists in the West are more likely than not to leave –or attempt to leave– the West in order to fight elsewhere. This trend has been explained as the result of factors such as the opportunity to travel easily to fight abroad for a longer period, the availability of training to increase operational capabilities and the existence of norms according to which fighting abroad is perceived to be more legitimate.

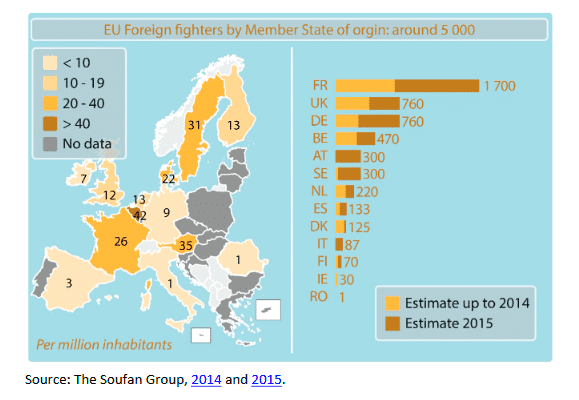

Muslims –including in this term not only mindful followers of Islam but persons having a Muslim cultural background– from EU nations account for around one-fifth of the 27,000 to 31,000 individuals who, from 2012 to the end of 2015, had travelled to join jihadist organisations in Syria and Iraq. They primarily went to join the so-called Islamic State –known between April 2013 and June 2014 as Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIL)– but also the al-Qaeda branch based in the first of these two countries, and other smaller entities also active in the area. However, no more than 20 million Muslims were living in EU countries, which means these are approximately 16 times overrepresented among the foreign terrorist fighters in Syria and Iraq compared to figures for Muslims traveling from other regions of the world.

Against the background of all these developments, the purpose of these remarks is, first, to reflect on the differences in the levels of the most recent jihadist mobilisation that can be observed in the various EU nations. Secondly, it aims to deal with a factor usually forgotten when discussing why Western European governments have problems accommodating some of the descendants of immigrant Muslims. Finally, this article discusses how jihadist organisations based abroad can exploit both favourable conditions for recruitment within certain Muslim congregations and the religious cleavage within EU countries.

Towards a differential analysis

“Neither a multiculturalist approach, such as the one long pursued in the UK, nor the pervasive assimilationist policies adopted by France, have succeeded.”

The unprecedented jihadist mobilisation in the EU has not plagued all member nations uniformly, which is a relatively overlooked reality. Contrary to what is often taken for granted, the EU countries to be most seriously affected by this recent jihadist radicalisation are neither necessarily defined by having the largest number of Muslim inhabitants nor by having the highest percentage of Muslims as part of their total national populations. Leaving aside the case of Cyprus, because of the exceptional circumstances concurring in this divided island, Bulgaria is next among EU countries with respect to the highest percentage of Muslims as part of its total population. However, very few Bulgarians are known to have travelled to Syria and Iraq as foreign terrorist fighters.

On the other hand, Italy and Spain rank among the top five EU states with the largest Muslim populations living within their territories. However, figures for the number of nationals or residents in these two countries that have left to become foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq, as well as for their proportion with respect to their corresponding national populations in general and their Muslim populations in particular, are rather low. Therefore, if countries affected in a particularly serious manner by the most recent jihadist mobilisation taking place across the EU are not necessarily those where Muslims register the highest proportions with respect to the national populations nor of necessity those which concentrate more Muslim people, which ones are they?

The EU countries most seriously affected by this wave of jihadist mobilisation surely include large nations with large Muslim populations, such as France, Germany and the UK, but also smaller nations with relatively high proportions of Muslims as part of their populations, as in the cases of Austria, Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden. As opposed to the centuries-old Muslim population of Bulgaria or the first-generation immigrants that predominate among Muslims in both Italy and Spain, the common unifier for those other eight countries is the fact that they all have Muslim populations composed mainly of second-generation residents, descendants of immigrants who left their Muslim-majority homelands in Africa, the Middle East and South Asia decades ago.

A generalised identity crisis among young, second-generation descendants of immigrant Muslims in Western Europe’s wealthiest countries appears then to lie behind the most recent unprecedented jihadist mobilisation. Migrant descendants born or socialised in an EU country are often caught in an odd balance between cultures and are especially prone to identity crises connected with a diaspora situation. Too many of them have developed little, if any affection, for the EU nation in which they were born or raised, even though they show scant attachment to the nation from which their parents or grandparents originate. Jihadist propaganda offers an extreme, violent solution to these people’s identity conflicts, luring them with a different concept of nation: the nation of Islam as promoted by Islamic State and also al-Qaeda.

Policy failure, but also Salafism

“Within the Muslim collectivities themselves there are dynamics pushing towards self-marginalisation and self-exclusion from the mainstream open society.”

What the figures on foreign terrorist fighters suggest is that the EU countries in general and Western European governments in particular have a serious problem in accommodating a more than significant portion of second-generation Muslims amidst their heterogeneous and pluralistic societies. Their institutions and civil society entities are failing to persuade thousands of young second-generation Muslims –irrespective of their socioeconomic and educational backgrounds, which are no key to predicting the appeal of jihadist attitudes and beliefs– that their religious identity is compatible with their identity –or multiple identities– as citizens of liberal democracies. Neither a multiculturalist approach, such as the one long pursued in the UK, nor the pervasive assimilationist policies adopted by France, have succeeded.

But flawed institutional policies and the inadequate performance of civil society entities are not only to blame for the lack of accommodation experienced by considerable segments of second-generation Muslims in EU countries. Within the Muslim collectivities themselves there are dynamics pushing towards self-marginalisation and self-exclusion from the mainstream open society. These dynamics advocating segregation result mainly, though not only, from the doctrinal and organisational efforts of Salafist religious leaders and congregations. These efforts are often pursued in places of worship and in households, but also in prisons, attracting many among young second-generation Muslims born or raised in Western European countries but suffering from identity conflicts and in quest of meaning or structure in their lives.

While, in its traditional version Salafism presents itself as a quietist orthodox brand of Islam, respectful to established authority, it is also a fundamentalist and politicised religiously-based ideology. Salafism as a rigorist understanding of the Quran and the Hadith leads its followers to believe that liberal democracy is haram or prohibited from an Islamic perspective, that there is an intrinsic incompatibility between Islam and democracy, and that Muslims living in majority non-Muslim countries should actually resist social integration and behave in such a way as to drastically restrict and regulate, particularly but not solely when it comes to women of their own closed communities, any interaction with the rejected surrounding society –presented in typically antagonistic terms as a secularised and impure infidel environment– in order to avoid corrupting influences and thus affirm what they claim to be the true faith of the Prophet Mohamed.

This all implies a very serious middle to long-term challenge to the basic social cohesion of Western European nations, added to other socio-political antagonisms. Not only because Salafist congregations and organisations established in EU nations purposefully reach out to Muslim immigrants or Muslim-immigrant descendants whose original Northern African or Middle Eastern religious tradition derives from a distinct, far more adaptable, and tolerant understanding of Islam. Also because they are comparatively more efficient in incorporating individuals to their associations due to, among other advantages, financial support from transnational Salafist networks and ultimately from affluent public authorities and private donors located in countries of the Arabian Peninsula where, Saudi Arabia being the unavoidable reference, Salafism is the exclusive religious confession.

What terrorists can do

“Each time a terrorist attack is perpetrated, jihadism is to be thought of not just as a national security problem but also as a challenge to the very fabric of open societies.”

Salafism continues to gain influence among Muslims in the EU and, despite the many different interpretations of Islam existing among them, play a central role in conditioning how Muslims deal with their religious traditions in Western societies. This has sometimes been the unexpected or uncalculated consequence of poorly-informed decisions, adopted on the spur of the moment and often in the context of broad religious policies or radicalisation-prevention programmes, from the local level of government to the national one and including intermediate provincial and regional authorities. Probably out of ignorance, EU politicians and policymakers, when confronted with the problem of jihadist mobilisation, seem prone to think about peaceful Salafists –because they present themselves as peaceful, disregarding their fundamentalist credentials– as the best partners against violent Salafism. Contrary to what has been asserted, also from within academia, the emergent trend of sectarian and puritanical Salafism in Western Europe has not produced the ebbing of jihadism. In fact, far from becoming an obstacle to radicalisation in prisons by attracting young incarcerated Muslims, jihadism has boomed in penitentiary systems such as France’s, were Salafism was even institutionalised.

A first implicit risk in this kind of partnership is that of empowering those who preach the incompatibility of Islam and democracy at the obvious expense of moderate Muslims who, also part of our own societies but loyal to our institutions as a result of conviction and not of convenience, think the opposite in this respect. This would amount to facilitating the growth of Salafism among Muslims living in Western European nations, moving people away from ordinary social life to deliberately segregated collectivities with patterns of behaviour in contradiction with those common in open societies. As a consequence, Muslims as a whole might be perceived with increasing distrust by non-Muslims, potentially widening an already emerging religious cleavage, as unfavourable views of Muslims appear to be on the rise in the main EU countries.

The more Salafism as a fundamentalist version of Islam, as well as the inward-looking Salafist congregations, become attractive to identity-seeking and disenfranchised second-generations Muslims in EU countries, the easier jihadist organisations based abroad will find it to recruit young individuals, willing to make the transition from orthodox quietism to jihadist terrorism, by focusing on potential recruits already familiar with Salafist tenets and using Salafist entities as gateways. Also, terrorists acting under the attitudes and beliefs promoted by the bellicose strand of Salafism –that is to say, by Salafist-jihadism or, plainly stated, just jihadism– can exploit and widen the social fracture between Muslims and non-Muslim in the EU countries alluded to in the previous paragraph.

Indeed, they now do so every time a jihadist attack is successfully perpetrated on Western European soil and it could even be said that as long as jihadist terrorism remains a credible threat for Europeans, even if perceived differently depending on the country. This threat can currently manifest itself, as is well known, through a variety of possible expressions, ranging from terrorist attacks carried out by lone actors or isolated cells to acts of terrorism prepared and executed by small groups of individuals having some kind of connection with jihadist organisations based abroad or acting in a more complex and centralised mission planned by the senior leadership of Islamic State or al-Qaeda. Each time a terrorist attack is perpetrated, jihadism is to be thought of not just as a national security problem but also as a challenge to the very fabric of open societies.

(*) This commentary is a short version of ‘Jihadist Mobilization, Undemocratic Salafism, and Terrorist Threat in the European Union’, published in Georgetown Security Studies Review (Special Issue, February 2017).