The original version in Spanish was published by Agenda Pública

Challenging European institutions seems to be catching on. In September the Commission took Poland to the Court of Justice to force it to preserve the independence of its own Supreme Court. At the end of October, the head of Europe’s Brexit negotiation team, Michel Barnier, repeated for the umpteenth time to Prime Minister Theresa May that her Chequers plan is unworkable and that the Commission’s red lines are not flexible. Finally, the Commission also rejected Italy’s proposed draft budget because of how seriously it breached prior fiscal commitments, including an increase in the deficit to 2.4% of GDP, three times higher than originally agreed. This is the first time in the euro’s history that a draft budget has been rejected.

As a result, political collision seems inevitable. With the odd bedfellows Matteo Salvini –leading the xenophobic far-right Lega– and Luigi Di Maio –head of the 5 Star Movement, originally left-wing and ‘anti-system’ but now hard to categorise– in the Italian government, it is unlikely to be intimidated by Brussels although it could buckle under market pressure, as other Southern European countries did during the euro crisis.

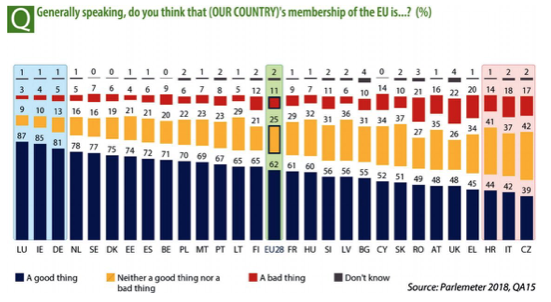

Italy’s draft budget is explosive, combining the Trump-style tax cuts desired by the Lega with the increased spending demanded by the 5 Star Movement, in the form of higher minimum pensions and long-term unemployment subsidies –that could be akin to a minimum basic income–, further aggravated by a reduction in the retirement age that makes Brussels particularly uncomfortable. Nevertheless, the budget should be no surprise. The Italian government promised higher expenditure, a perfectly natural policy for a country that has been economically stagnant for two decades and whose infrastructure is literally collapsing, although it has so far not suggested an increase in revenue to fund a fiscal expansion that might satisfy Brussels. Hence, the President, Sergio Matarella –who could reject the budget as unconstitutional for violating prior Italian commitments to the EU– will very likely raise no objections in order to prevent ‘Europe and the establishment reject Italy’s budget’ from becoming the war cry of the government coalition’s campaign for the European elections next May. According to the latest Eurobarometer only 42% of Italians believe that EU membership is beneficial for Italy, six points less than the British, who are quitting the Union, and 30 points less than the Spanish. Clearly, the anti-Europeanism is a good selling point in Italy.

For its part, the Commission had no choice but to reject the draft budget, since it deviated so unjustifiably from what had been agreed, unlike the cases of other countries from which explanations were requested like Belgium, France, Spain, Slovenia and Portugal.

Italy should send the Commission an amended budget, although it most likely will not. The gesture of one of the Lega’s MEPs was highly revealing: after Commissioner Pierre Moscovici had presented the Commission’s opinion of the Italian budget he purposefully placed his shoe on top. Everything seems to suggest that Italy will continue challenging the Commission because it is not too concerned about possible sanctions, which would only be imposed in the spring of 2019 and be subject to a long list of conditions: that it is finally agreed that Italy’s debt is not on the right downward trend –since the deficit is below 3% it cannot give rise to sanctions–, that the data published next year support that conclusion, that the Commission proposes sanctions, that the Council approves them and a number of other aspects of the tortuous Stability and Growth Pact that needs reforming to make it simpler and more transparent…

“ (…) the real worry is that if Italy fails to improve its growth potential through the medium of reforms, it will find it increasingly difficult to remain in the euro”.

But the Italian government is aware that it will have to back down if the country’s risk premium shoots up as a result of both the budget and the subsequent confrontation with the Commission. After all, most Italians are dissatisfied with the EU but they do not want to leave the euro (similarly to the Greeks in 2015).

The question is how much market pressure will be required for the government to give way. From statements made the leaders of the government coalition it can be surmised that they will not budge until country risk is above 400 basis points, perhaps because they have done their maths and believe that up to that level the higher cost of debt will still not offset the budget’s fiscal stimulus, although that remains debatable. In any case, the government knows that the markets want growth, the budget is expansive and the country has some structural strengths that are often overlooked –such as a primary fiscal surplus, a current account surplus and a net positive international financial position (something Spain, for instance, lacks), while most of its public debt is held by Italian and not foreign savers–. Furthermore, for the time being the ECB is buying Italian debt via its quantitative easing programme and will continue to do so while credit quality does not decline (in which case it would not serve as collateral). All this suggests that the markets may take some time to react –with an Italian risk premium currently at 320 basis points– and instead wait and see if the situation is resolved before Italy finds itself on the ropes. As a backup, it appears that the Italian government has asked Russia for financial support, as Greece did at one point, although that would be an unlikely solution: Italy, after all, is still a richer country than Russia.

Although the Italian government’s style –especially Salvini’s– runs against the grain of Europe’s habitually suave diplomacy, there is still a window of opportunity for tension to wind down. This could happen if the markets put on more pressure, Italy begins to see the wolf at the door and the government makes minor changes to the budget –as regards, for instance, the age of retirement, certain items of expenditure or a proposal to increase revenue–, leading the Commission to finally approve the budget.

However, there is no guarantee that things will ultimately work out that way. Beyond Italy’s confrontation with the Commission, the real worry is that if Italy fails to improve its growth potential through the medium of reforms, it will find it increasingly difficult to remain in the euro. Since 1999 Italy has lost 20 per capita income points relative to Germany and today its income level is still roughly the same as when the euro was introduced. This is unsustainable over the long term. It is bleak outside the Monetary Union but, for many members, the euro at present is an unhappy marriage whose cost of divorce is simply too high. It must be made to function better.