Maybe it is, but it could take a while in global presence terms. Following the episodes of financial turbulence and a cooling of growth rates and expectations in China, there is a rising debate on whether the other Asian giant, India, could now take the lead in several domains (from economic growth to global governance).

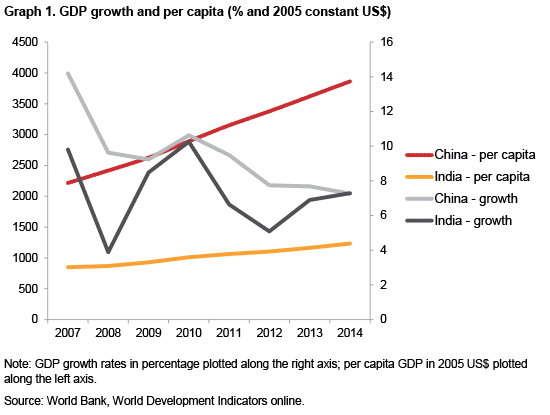

The capacity to actively shape global governance is linked to several factors, including the size of the economy. China is the 2nd largest economy in nominal terms (according to World Bank data), while India is 9th. There might have been a certain convergence of growth rates in recent years but there is still a huge and widening gap in other relevant indicators, such as per capita GDP. While India’s per capita GDP has increased at an impressive annual rate of 7% between 2006 and 2014, China surpasses that figure with a 12% annual increase (Graph 1).

India has not been inactive in regional or global governance initiatives (for instance, it will be hosting the 8th BRICS Summit by the end of this year). The question now arises on whether India has the capacities, the need, and the will to increase its profile as a global actor.

Answering this question would require an in depth analysis of India’s development strategy, macroeconomic features and foreign policy. One tool that could partially contribute to this debate (on the capacity side) is the Elcano Global Presence Index that assesses the volume and nature of countries’ external projection.

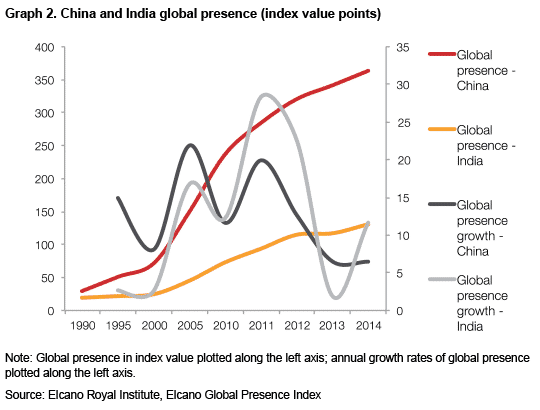

China’s entry in the global scene has resulted in an impressive record in global presence terms. Between 1990 and 2014, this figure has grown at an annual rate of almost 48%. Therefore, Chinese global presence multiplied by 12 during this period. Here again, India’s performance is impressive but slower, with an annual rate of growth of 24% (Graph 2). The very different performance of these two countries in global presence terms is partially explained by the differences in their development strategies. While India opted for a domestic-based development model that should rely on the expansion of domestic demand, China chose an outward-looking strategy strongly based on the external demand of local manufactures.

A closer look at the 2010-2014 period shows an acceleration of global presence growth rates in India, compared to China’s. However, it is too soon to conclude whether this change of trend in global presence growth is the result of a change of strategy in one or both countries or whether it simply responds to exceptional factors.