Reading decree nº 2,323 in the Official State Gazette of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, whereby President Nicolás Maduro Moros declared a “state of exception and economic emergency” on 13 May, is instructive. Not only because it contains profuse allusions to foreign conspiracies against the regime, authorises military deployments and exercises and bestows responsibility for “public order and national sovereignty” on the Local Committees for the People’s Provision (CLAP), which, controlled by the regime, distribute the few foodstuffs and essential products that are imported. And not only because it is so free and easy with Treasury funds. It is instructive because in the second paragraph it refers to “the physical departure of President Hugo Chávez Frías, which occurred on 5 March 2013”. In other words (although the expression has been used on other occasions), in some non-physical sense he is still present.

Marx famously wrote,

“Hegel remarks somewhere that all great, world-historical facts and personages occur, as it were, twice. He has forgotten to add: the first time as tragedy, the second as farce”.

Maduro is the farce to Chávez, but a farce that has mutated into tragedy, and looks likely to end badly. The ascent of Hugo Chávez via the ballot box (after an earlier attempted coup) can be explained by the preceding corruption and inequality, although his regime fell into a level of corruption that was equal or worse and took over a good deal of State institutions. He distributed money amongst the most needy –today it would be called “helicopter money”–. But he did not invest in the country’s future, despite the vast income from oil. He even dismissed from PDVSA, the state-owned oil company, almost all those with technical and business expertise, thereby strangling his very own golden egg-laying goose. And this rich, albeit unevenly rich, country fell into self-inflicted disaster.

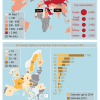

The chaos reached unimaginable dimensions with Chávez’s “physical departure” and the arrival, orchestrated by the deceased, of Maduro. The queues to buy lavatory paper and the lack of medicines, food and staple products are steering the country towards disaster and the agony of the population, with an inflation rate this year of 720% that –according to the IMF– will increase threefold next year. This is without mentioning political prisoners, such as Leopoldo López. In this context the opposition, which is diverse but organised around the Table of Democratic Unity (MUD), comfortably won the parliamentary elections last December, after 17 years of a chavismo that had always won in the polling booth at a national level (albeit controlling all the country’s institutional machinery).

What shall be the outcome of this all? The right one, the democratic and peaceful outcome, would be a recall referendum as provided for in the Bolivarian constitution itself. Chávez submitted himself to one in 2004 and won it, although the opposition alleged fraud. But this time the regime, or Maduro himself, is resolved to block it because he knows that he would lose. And to this end he is using or is going to use all the resources at his disposal: the police against the demonstrations, the Supreme Court, which he controls, against the vote opposing the decree passed by the National Assembly, now dominated by the opposition. And a National Electoral Commission (CNE) that may prevaricate weeks and months in its verification of the 1.85 million signatures collected to force the recall referendum.

Attempts are being made by mediators to establish a dialogue on politics and the economy. In the name of Unasur, the former premiers José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, the Panamanian Martín Torrijos and the Dominican Leonel Fernández are doing what they can. The Spaniard has indicated that willingness exists, but has also warned that ‘the road will be long and arduous’. There are many vested interests at stake. Some ask for the mediation of China, to which Venezuela owes US$65 billion in exchange for oil, or the Organisation of American States. The regime has been left without allies, or at least without certain friends such as Cristina Kirchner in Argentina and Dilma Rousseff in Brazil, suspended in a way that Maduro has carefully looked into.

The country that can have a bearing is Cuba, which pulls many of the strings in the chavista regime, although I do not know what was said in this regard to President Raúl Castro by the Spanish Foreign Minister, José Manuel García-Margallo, in his recent visit to Havana. Venezuela is one of the few levers of regional power still left to the Castro regime, which is now normalising its relations with the US and with Europe.

Dialogue is necessary to find a peaceful and democratic solution. There is a danger that is spoken about more and more openly in Caracas and that the leader of the MUD, Henrique Capriles, has mentioned but not endorsed: that the armed forces intervene and depose Maduro and his crew. Despite the years that have gone by, despite the purging and the promotions, and despite gaining economic power –and with his decree, Maduro has given them even more power– not all the officers are Chávez-supporters, still less Maduro-supporters. Certainly there will be many who cannot bear to see the chaos, a growing insecurity not only in the countryside but also in the cities –Caracas has become one of the most dangerous cities in Latin America– and the disastrous management of the President and his government. But nor should one jump to erroneous conclusions: should they intervene, the armed forces will not necessarily remove power from Maduro and simply hand it to the opposition.

The pressure is increasing. The leaking of a US report warning of an ‘implosion’ is no coincidence, but nor is its thesis very wide of the mark.