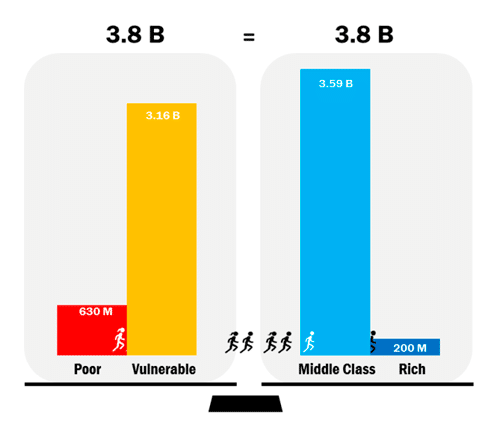

The middle and wealthy classes now account for more than half the world’s population, rather more than 3.8 billion people, a majority. This is the conclusion of a World Data Lab report covering 97% of the world’s population and published on the Brookings Institution blog. This is a clear tipping point in global development.

Kristofer Hamel and Homi Kharas, of World Data Lab, define members of the middle class as those who spend between US$11 and US$110 a day (in 2011 purchasing power parity). Extreme poverty is deemed to include those who spend less than US$1.90 a day, while people who are between the two categories are classified as vulnerable, and those who are above the US$110 threshold as ‘rich’. The impact of the latter on global household consumption is limited. Two thirds of such spending comes from middle-class expenditure. It is made up of households that are able to afford such consumer durables as motorcycles, washing machines and fridges and, Hamel and Kharas explain, they can make such purchases without fear of falling back into poverty. This lack of fear is also a feature of belong to their socioeconomic category. The prospects foreseen by the model go even further: 4 billion middle-class people by 2020 and 5.3 billion by 2030. According to the predictions, each of the middle-class markets in China and India will by then almost be on a par with that of the US.

This is a marked improvement in the global situation and goes hand in hand with the reduction in poverty, to a large extent thanks to what globalisation has wrought in certain aspects (conveniently overlooked by the anti-globalist Trump). According to the World Data Lab’s figures, one person escapes from extreme poverty every second and five enter the middle class. Despite this, an unrelated report drawn up by various UN agencies argues that hunger in the world has risen over the past three years, affecting 821 million people, which is the same as a decade ago and a definite setback.

The growth of the middle classes is unprecedented and highly significant. The phenomenon is absent in only a limited number of countries where the middle classes have shrunk. Statistically what is happening in China and India –the world’s most heavily-populated countries– is of great significance, as it is in Asia generally, from where nine out of 10 of the next 1 billion middle-class consumers will come. But the trend is widespread and has political consequences because the middle classes are more demanding in their insistence that governments should provide decent infrastructure and public services, institutional improvements and a functioning and reliable rule of law.

Of course, such an enormous achievement does not eradicate two problems. The first is that the growth of the middle classes does not prevent certain countries from falling into what has been dubbed the ‘middle-income trap’, a type of development that enables economies to reach a middling rank, where they proceed to get stuck. How such countries assimilate the technological revolution will be decisive in this respect. If it is to be achieved and global technological justice secured, as I and my colleagues have argued, public and private policies will need to be devised at a global level.

The second problem is that the emergence of middle classes in developing countries could clash with some of the interests of the middle classes in the developed world, who do not want to end up worse off, as occurred in the recent crisis and its uneven recovery and aftermath. A conflict of interests of this kind strengthens the populist arguments that are fuelled by the discontent among middle and lower classes that have fallen on harder times. Policies are needed to prevent such a confrontation and that implies a challenge if globalisation, in a reformed guise, is to continue and generate the fairly-distributed wealth that has given birth to a global middle class: a welcome revolution indeed.