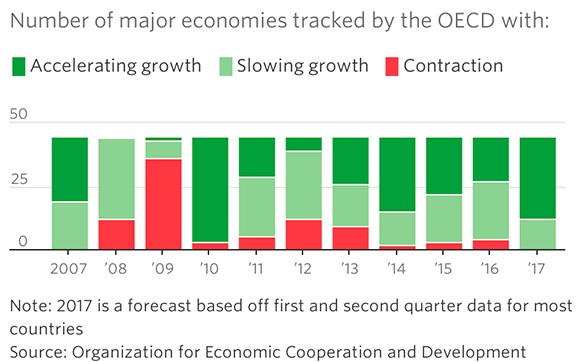

After several years of the global economy growing at an increasingly slower rate, most countries –including advanced, emerging and developing economies– have experienced strong synchronised growth since the middle of 2016 and especially in 2017 (see Graph 1).

Source: The Wall Street Journal.

If such a tendency consolidates, we could (at last) be leaving behind that last remains of the Great Recession with followed on the heels of the global financial crisis of 2007-08. Increasingly, more and more indicators point in that direction: according to the World Trade Organisation (WTO), after years of stagnation, international trade will grow 3.6% in 2017, one third more than the WTO itself had forecast just months before. The price of oil, also a good indicator of the strength of global demand, is rising again and now approaching the levels of early 2015 (around US$60 per barrel) when it began its plunge to below US$35 per barrel. At the same time, both the European and Japanese economies are growing faster than previously projected, the US remains at cruising speed and is back at full employment, there is less concern about an abrupt deceleration of the Chinese economy, India has managed to accelerate its growth rate even more, Russia and Brazil have come out of their intense recessions of recent years, and Mexico, the country most exposed to Trump’s braggadocio, should soon also see its growth rate pick up.

“If growth does consolidate, then the ‘secular stagnation’ hypothesis […] might just turn out to have been a bad dream”

Geopolitical risks –which grew in 2016 and climaxed with Brexit and the election of Trump– have also diminished noticeably (with the exception of Catalonia). The UK’s exit from the EU does not imply the beginning of the end of the European Community project and it looks like Trump will carry out hardly any of the economic promises from his campaign. He will not take the US out of the WTO or withdraw from NAFTA, he will not spark trade wars with China or Germany, nor will he deliver a significant fiscal stimulus or revoke Obamacare. His rhetoric will remain provocative, but it is increasingly less likely that the White House will actively work to destroy the open, liberal economic order which has sustained the growth and development of the global economy for decades. It is different matter, of course, that the Trump Administration will not lead global governance initiatives, or that the tensions between the US and North Korea are likely to increase. However, the probability that any of these possible developments will be systemically destabilising is low. For the EU, paradoxically, the combination of Brexit and Trump, together with the election of Macron in France and the re-election of Merkel in Germany, could be a salutary lesson for the integration process. Brexit and Trump could serve as external ‘federalising’ shocks and help to reactivate the Franco-German axis (lacklustre in recent years due to French weakness), opening the way to further progress in governance in the Euro zone.

If growth does consolidate, then the ‘secular stagnation’ hypothesis –which has dominated macroeconomic debates since Larry Summers revived the use of this old term in 2014– might just turn out to have been a bad dream. Those who defend this idea have maintained that advanced economies are condemned to low economic growth due to structural factors such as an aging population, increases in inequality (which depresses aggregate demand) or high levels of debt. They claim that growth will only be possible if low interest rates are indefinitely maintained (with the concomitant risk of new bubbles) and if fiscal stimulus is more deeply pursued (with the resultant increased debt), and they point to the absence of inflation as confirmation of their thesis.

On the other hand, there are those who believe that the weakness of the recovery has been the consequence of the severity of the financial crisis and the slowness with which the financial system, along with businesses and households, cleaned up their balance sheets. Although both schools of thought share a preoccupation with the low rate of productivity growth, the pessimists argue for demand expansion (although they are sceptical of its effectiveness) while the others are inclined to plead for patience and engage in supply-side reforms to increase the potential growth rate.

The problem with the ‘secular stagnation’ hypothesis is that it is not falsifiable. But as we have pointed out, the thesis might begin to lose its relevance. While it is true that inflation has not yet shown signs of rising (not even in those economies operating at full employment levels), and that this may begin to present a puzzle to central banks –which would like to normalise current monetary policy by slowly raising interest rates as soon as possible in order to have margin to reduce them when the next crisis arrives–, the data shows that the risks of deflation have definitively passed and that consumer confidence is rising.

In short, without ignoring the enormous structural challenges facing the global economy, it is possible that the risk that growth will remain too weak to improve the expectations of an increasingly frustrated population is diminishing.