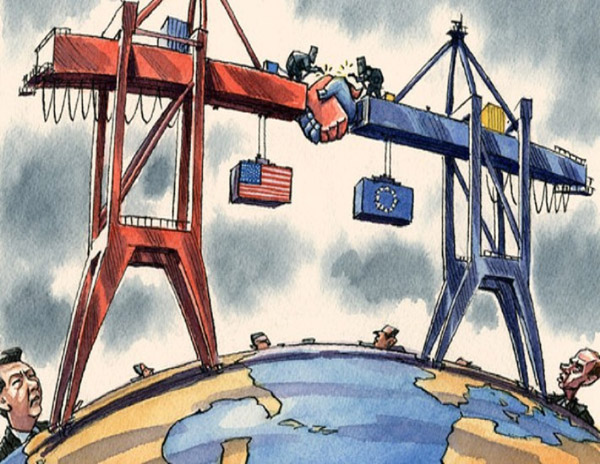

The TTIP, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, is one of the most ambitious projects on the US and EU agendas, not only in economic but also in geopolitical terms, given what it can mean to those involved, and even to those who will not be part of it. It set off with great enthusiasm, but the momentum in now slowing down. The idea was to finalise it this year in order for it to be ratified in 2016, before the end of Obama’s second term. Now the hope is to conclude it by early next year, although it is far from certain that it will be ratified with Obama in the White House.

The negotiations, which are extremely complex, are still in a technical phase but will unavoidably enter a more political dimension by the autumn. Progress is slowing down as public opinion has become more negative, as recognised by the negotiators themselves. In the US the support of the labour unions is wavering, as are the Democrats. It is the latter, not the Republicans –who are in favour–, who have refused in the Senate to provide the President –a Democrat– with the authority to finalise negotiations on the TTP (Transpacific Trade Association), which by extension will also apply to the TTIP.

In Europe opposition to the TTIP is also growing, especially among the German social-democratic left (a partner in government) and opposition parties, while it is rising in Austria, France and in the European Parliament, and, generally, in the more radical left. Suspicions are not being fuelled by protectionism but rather by doubts about whether safeguards for consumers (for instance as regards genetically modified organisms), workers and the environment will be maintained. To this is added the debate on how to protect investors without enabling major companies to take states before arbitration panels in the event of considering they are being discriminated against. This type of action has increased enormously, with only 10 cases in 1994, rising to an estimated 600 by 2021). To overcome this hurdle, the European Commission is now proposing the creation of a Global Investment Court in order to multilateralise the issue in what should be the biggest change in the system of international arbitration in decades.

In part, the negative environment has also been generated by the lack of transparency with which the EU’s negotiators have conducted the process as far as public opinion is concerned (unlike the economic players involved, who have been in permanent consultation). For some time now they have attempted to remedy this, but the negative dynamic was already under way. Many negotiation documents are available on the Commission’s website. But who consults them? Who, beyond the experts, knows that it is a senior Spanish official, Ignacio García Bercero, who is leading the negotiations in Brussels under Commissioner Cecilia Malmström?

The alleged economic benefits of the agreement are also shrinking. When it was launched in 2011 from the Center for Transatlantic Relations it was said that the initiative could permanently boost GDP per capita on both sides of the Atlantic by 3.5%, or the equivalent of one year’s additional salary in the working life of every US and EU citizen, and create 7 million new jobs. Newer studies cut back the expectations, although the agreement’s promoters, Dan Hamilton and others, have brought new data to bear that place it in a post-crisis context.

The TTIP is an opportunity for the US, but also for Europe, to maintain a certain weight in a world whose centre of gravity is shifting to Asia and to somewhat slow-down the world’s de-westernisation. In fact, it might favour the ‘pivot to Asia’ pursued by Washington. The TTP –which involves 11 countries, including Japan, but not China– along with the TTIP would set the US in a strategic position to control trade and investment rules in the two geographical areas, and globally. The transatlantic economy is the world’s largest, accounting for 50% of world GDP in value and for 41% in terms of purchasing power. It generates US$5.3 trillion and employs 15 million people, mostly in quality jobs. And along with the TTP –which accounts for 40% of the global economy and a third of global trade– the US would be at the centre of a dual zone covering two thirds of the world’s economy. For Europe it would be a way of regaining influence. But is China really going to stay on the sidelines and do nothing? In fact, China is already active.

Criticism has also focused on the fact that the new ‘plurilateralism’, as Martin Wolf calls it, practiced by the US discourages multilateralism and the acceptance of global rules through the World Trade Organisation (WTO). However, the famous Doha Round has given rice to only scant results since it opened in 2001.

In Spain the Ministry of Economy is openly in favour of the TTIP, and so is the Socialist Party, although under conditions. Such an agreement could provide Spain with some very specific advantages in terms of automobile, footwear, textile, fruit and vegetable and canned fish exports and of public procurement contracts (in infrastructure works if the sector really opens up in the US, which would it also does so in Europe). Unfortunately for Spain, given the growing strength of the Hispanics in the US, France managed to exclude cultural products from the agreement from the very beginning. Neither does it seem possible to achieve a very difficult regulatory convergence for financial products.

Although the agreement could put Latin America in a difficult situation, Spain could subsequently act as a bridge to incorporate a truly Atlantic concept to the project. If Kishore Mahbubani spoke some years ago of the ‘Asian Hemisphere’, can we now talk of an ‘Atlantic hemisphere’? The largest oil and gas discoveries of recent times are in the Atlantic and are transforming the world. But without the whole of the Americas and West Africa, the Atlantic will always be incomplete.