After drones have become cheaper and almost commonplace, making them available today to any armchair aviator, the new possibility is printing plastic guns at home that are able to fire real bullets. The technology involved is 3D printing –by way of microjets that print layer upon layer of plastic to produce increasingly complex objects–, which is becoming far more affordable. A printer of this type, capable of producing a gun, can be purchased for just over €1,000 and some have predicted that many would be sold over the Christmas holidays. Naturally, a computer program is also necessary, but there are groups such as Fosscad (Free Open Source Software & Computer Aided Design) that are working to release such a program free of charge. The threat of a coming proliferation of light-weight firearms is something about which states –let alone the international community– can do little, but some sort of response will certainly become necessary.

This is all part of the process of the diffusion of power –of the emergence of micro powers, what some of us call ‘the power of the few’–, which can materialise in many different ways, not least in the technological dimension. The authorities are afraid that there will arise new possibilities for violence that are likely to spread uncontrolled, although terrorists and criminals already have their own sources of standard weapons. However, an added problem is that printed guns are made of plastic and contain very little metal (so far only the spring, the tip of the firing pin and screws in addition to, of course, the cartridge), making their detection difficult. A team of reporters from the London Mail on Sunday printed and assembled one of these guns and travelled with it undetected on the Eurostar, the high-speed train linking England to the Continent. In a country as permissive with weapons as the US, the legality of these firearms is in some doubt, although the Undetectable Firearms Act forbids possessing arms that cannot be spotted by a metal detector. But the US Congress has so far failed in its attempt to truly ban ‘printed’ weapons. Nevertheless, information and security services worldwide, including Europol, are attempting to control a growing wave of cybercrime, including the possibilities offered by new technologies such as 3D printing.

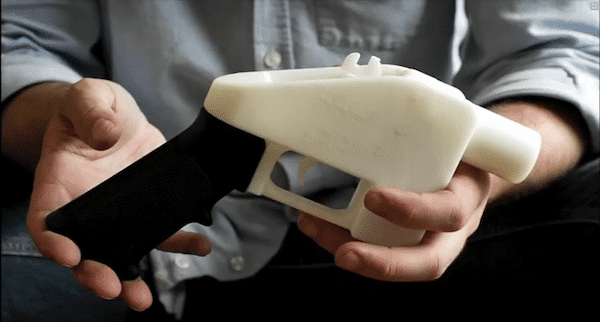

The first gun to be printed in 3D, in pieces ready to assemble, was inappropriately dubbed the Liberator. It was capable of firing a single shot and was built in May 2013 (with a second-hand printer that cost €6,500, plus a little extra for the plastic) by Cody Wilson, a Law student at the University of Texas who calls himself a ‘crypto-anarchist’ and claims to be defending freedom. Since then the technology has progressed considerably and has become cheaper. Both plans and computer programs now proliferate on the Internet. As recounted by Nick Bilton (The New York Times), members of Fosscad are cooperating to develop a semi-automatic pistol that is 90% plastic.

This is a global trend. Last May, the Japanese police arrested the 27 year-old Yoshimo Imura in the city of Kawasaki. He had manufactured a gun capable of firing six consecutive 38-calibre rounds. He named it Zigzag, like the German Mauser. ‘A gun makes power equal’, he claimed in his video. Indeed, YouTube is full of videos on the subject. Some of these guns do not even have a traditional shape. In Canada even a rifle has been printed.

A certain amount of knowledge is necessary to print a gun. It is not that easy to calibrate a 3D printer for these purposes and some fairly complex challenges can arise. But the process is getting easier all the time. The only component that cannot be printed is the cartridge, which still has to have a metal bullet and case. Better said: it cannot be printed yet. Experts believe that the time will come when it will be possible –at least as regards the parts necessary to produce cartridges–, and sooner rather than later. In fact, a year before the Liberator was presented to the public, the US believed such a thing was impossible. And that was just the beginning.