The West, and several governments in the Middle East, have made a serious error of judgement with Daesh, the self-styled Islamic State or ISIS. They have looked at it from the terrorist perspective alone, equating it with al-Qaeda. But it is, in fact, a very different kettle of fish. It obviously uses terror in every sense of the word, and is even more dangerous as it has outstripped in brutality and media attention the network founded by Bin Laden. But if the latter and its franchises needed sanctuaries, Daesh is going for effective control of territory: hence using the name ‘State’, since the fundamental objective of its leader and self-appointed Caliph al-Baghdadi is to establish a caliphate. His self-appointment as Caliph has angered many Muslims although it has also gained him the allegiance of others.

His aspirations are global and he needs the Caliphate to attract radicals from the region and beyond and to impose his extreme version of Islamic law. Without territory, he would lack that legitimacy, both in his own eyes and in those of his followers. Therefore, it will be much more difficult to evict Daesh from the lands it occupies and from cities in Iraq and Syria than it did to dislodge al-Qaeda from Afghanistan.

A US Army officer, General Michael K. Nagata, who is head of Special Operations in the Middle East, recently admitted that we have not only ‘not defeated the idea’ of Daesh but that ‘we don’t even understand’ it. And, obviously, step number one in any strategy is ‘first know your enemy’. As noted by Graeme Wood in a long and documented analysis in The Atlantic, these people believe in an apocalypse, a forthcoming day of judgment (whose roots Jean Pierre Filiu brilliantly studied in L’Apocalypse dans l’Islam) that will de the result of a soon-t-come crushing defeat of an enemy and the subsequent expansion of a global caliphate that will stretch from Turkey to Spain.

The last caliphate –a type of state-religious organisation– was the Turkish Empire, whose steady decline was brought to a swift end by Atatürk in 1924. But Baghdadi (who is a Quraysh, a member of the tribe that controlled Mecca and in which the prophet Muhammad was born) the caliphate is important for him personally, as a means of salvation, as a focus for loyalty and to provide a ‘homeland’ to more than 20,000 foreign fighters from 90 different countries. This is in addition to what it signifies in terms of ‘righting’ the borders established in the Middle East by the Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916, which the movement disavows.

Hence, one of Baghdadi’s few public statements has been a sermon he delivered in Mosul a year ago, in which he announced the Caliphate’s establishment. Furthermore, it is vital for him to control territory in order to dispense social and economic justice (another Islamic precept), along with a certain degree of administrative order. By some accounts, despite the terror it makes use of, Daesh is not doing all that badly. Thanks largely to recycled Sunni Baathist officials from Saddam Hussein’s regime, especially the military who organised themselves in the Iraqi prisons in which they were incarcerated following the US invasion. Daesh has thus been able to extract and sell oil from the fields it has taken over, collect taxes and provide services. Meanwhile, Saddam’s former generals and officers, driven by a Sunni nationalist desire for revenge rather than for any hankering for a theocracy, have made considerable strides in professionalising the Daesh forces.

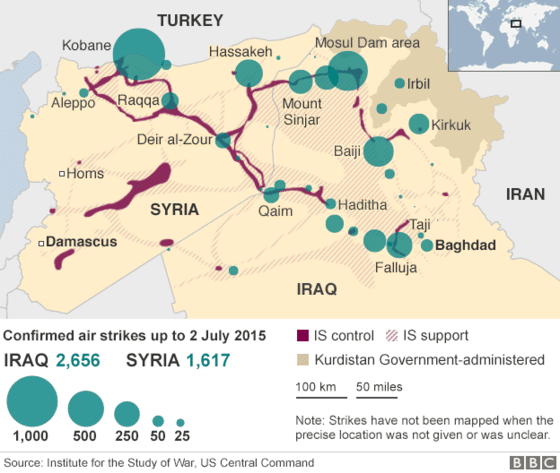

Al-Baghdadi needed to possess and administer actual territory in order to gain theocratic legitimacy, as Michael Weiss and Hassan Hassan have stressed in a commendable book titlled ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror. Should he lose control of his territory (an area similar in size to the UK but largely unpopulated), he will no longer have a caliphate, not only physically but in all other respects too.

Al-Baghdadi’s vision is still only a minority phenomenon, but no less dangerous for that. It is the first State in modern times to have been created by jihadists. To dislodge them, however, will be very difficult unless thousands of troops from other Arab countries become involved, and that is unlikely to happen. In fact, some believe Daesh can only be defeated by the Sunni, and not necessarily moderate ones, in Iraq and Syria. And that would involve a war between brothers. The solution does not lie in the hands of the Shiites or the Kurds, and even less so of the Westerners.

In any case, as noted in Madrid by the anthropologist Scott Atran, who in an attempt to understand not only the ideas but also the motivations behind Daesh’s followers has conducted highly interesting field studies on them, the caliphate can take many different forms. But it is an idea that has come to stay, and which can affect the world’s general political discourse. Although, as Atran has discovered, Daesh’s jihadists, especially the foreigners, are prompted more by the love of money and adventure that by any attachment to simple radical Islamism. And for that to work, territory is a necessity.