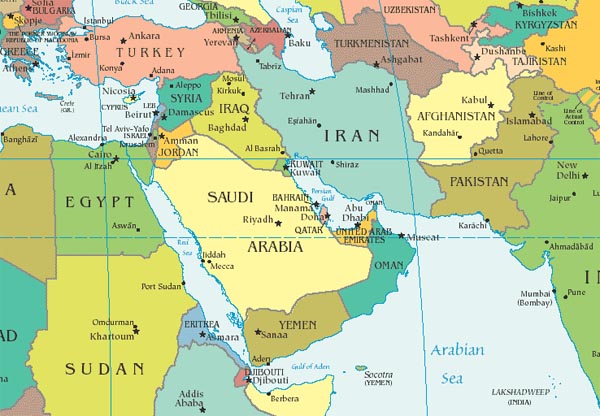

This Sunday is the deadline for the US and Iran to agree on limiting the latter’s nuclear programme to peaceful purposes. The current context is one in which the relations between Washington and Tehran, that had been interrupted since the 1979 hostage crisis, have again come to the fore, with new possibilities arising in the midst of the violent outbreak in the Middle East. Saudi Arabia is aware of this and will have to modulate its relations with both the US, its major ally, and Iran, its greatest rival. The deep change in this triad could mark a new era for the region. But it will not be easy.

In the background is the perennial rivalry between Sunnis and Shiites, which the former Iranian President Rafsanjani believes it is necessary to overcome. But also, and especially, the confrontation between states that want to imprint their brand of dominant Islam on the region. Rafsanjani has become the maker of proposals for a rapprochement with Saudi Arabia that never quite get off the ground due to the reluctance of both Riyadh and Tehran (Iran’s Foreign Minister has responded evasively to an invitation to visit Riyadh) and because the current conflicts in the Middle East, especially in Syria, have led the two countries to be at loggerheads. Rafsanjani has proposed a road map to move ahead, discussing Bahrain and Lebanon first, to then deal with Yemen and Syria. That is, the idea is to tackle the context rather than the text, building up trust through other countries in the region. Oman is playing a role in this approach, while Qatar is out of the picture following its support for the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt.

And then there is Iraq, where despite the confrontation between Sunnis and Shiites, neither Iran nor Saudi Arabia (nor the US) want to see the triumph of the Islamic State (the former ISIS), which has proclaimed a caliphate from the part of the country it occupies. It is a direct challenge from the Sunni camp to the Wahhabism promoted by the Saudi regime. In other words, the current problems in Iraq are leading the three members of this strange triad to move closer to each other.

The US has realised how important it is to move closer to Iran, which is why it has taken directly into its hands the nuclear negotiations whose deadline is 20 July. The other powers of the P5 +1 (the five permanent members of the Security Council plus Germany) are therefore now not leading but following. The deadline is provisional and could be extended for a further six months, but all parties know that failing to reach an agreement now would be highly detrimental (there are two major issues to resolve: the heavy water plant at Arak and the excessive number of centrifuges for a theoretically civil purpose). Saudi Arabia formally supports the negotiations but wants to see results, since a nuclear or pre-nuclear Iran would upset all its strategic calculations. In any case, it feels that US relations with Iran will change, changing its own relations with the US as well. Prince Bandar, who set Saudi Arabia’s security policy over many years, has been set aside and Prince Bin Nayef, seemingly more conciliatory towards Teheran, has taken his place.

The US also knows that this is the right time, since Iran’s President Rohani –no doubt with the support of Ayatollah Khamenei, the supreme leader– needs the gradual suspension of sanctions in order to improve the economic conditions of his fellow citizens. He must prove that the rapprochement with the West will be to his country’s advantage. The US, meanwhile, has left behind its attempt to end the nuclear challenge by toppling the regime. A nuclear agreement with Iran is the best way to normalise foreign relations with Iran, to ensure it ceases to be a rogue state and embraces moderation. This should change the dynamics in the Middle East, even if Israel is unwilling.