They are performing better than we Europeans, but not as well as before. The growth of the emerging economies is slowing down. Are we at the end of the Great Convergence, as Dani Rodrik suggested some months ago, or is this just a slowdown, as Martin Wolf saw it, a re-balancing of global growth? The IMF has changed its outlook frequently: a year ago the emerging countries were doing well; in the autumn they were doing worse and the Fund’s Managing Director, Christine Lagarde, announced various ‘transitions’; and this spring, although concerns focus on a possible deflation in the Eurozone, she warned that the ‘emerging markets face a complex situation’.

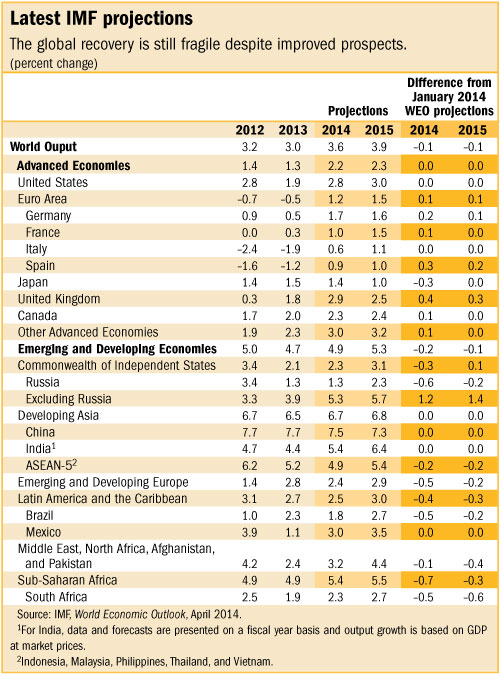

In its latest World Outlook, published last week, the IMF warned of ‘financial turmoil, equity outflows and difficult adjustments in some emerging market economies’. And it appealed to them to put their houses in order and carry out reforms to avoid serious risks. But at the same time it considers that the sharp recovery in certain developed economies, such as the US and the UK, has reduced the risk of a global slowdown. The fact is that the US is recovering –although the Federal Reserve reduced its liquidity injections, penalising some emerging countries– and the superpower is again acting as a locomotive.

In these past months the slowdown in liquidity injections (known as Quantitative Easing or QE) in the US has led to the withdrawal of capital from countries like Brazil and Turkey, on the lookout for higher returns. In fact, 60% of the capital directed at the emerging economies between 2007 and 2013 originated from action of the developed countries’ central banks. Furthermore, the new uncertainty is adding to the political crises in Turkey and the Ukraine –the latter with serious geopolitical questions attached– and to the devaluations in Argentina and Thailand. Thus, leaving aside China –which more than an emerging economy is actually a re-emerging civilisation–, the currently vulnerable large economies (India, Indonesia, Brazil, Turkey and South Africa) are now being joined by another group of fragile countries that have both fiscal and current account deficits. What’s more, it is advisable to be wary of the cooling-off in Latin America, especially in Brazil, whose growth rate is down to 1.8%.

Nonetheless, the emerging markets and the developing economies, as the Fund indicates, contribute to more than two-thirds of global growth, and, though to a lesser extent than previously, continue to grow: by 4.9 % in 2014 and by 5.3% in 2015. Growth like this would be more than welcome to many advanced economies. In fact, the BBVA’s research service believes that what it calls the EAGLEs (which it has reduced from nine to seven countries: China, India, Indonesia, Russia, Brazil, Turkey and Mexico, while Korea and Taiwan have now been promoted to developed economies), together with another 19 countries, will contribute 65% of global growth in the next 10 years, although 30% will still be attributable to China.

These forecasts envisage 1,000 million people in these countries leaving behind their status as poor or low-income individuals by 2025, and around 1,350 million people rising to join the middle classes over the coming decade. A further 195 million people should join the high-income segment compared with the previous decade. The grand peaceful revolution forges ahead.

China presently poses problems for many emerging countries, as its lower growth has led to a reduced demand for raw materials. The governments of many of these countries have not taken advantage of the conditions in the past to further industrialise, reduce their dependence on commodity exports and implement some necessary structural reforms. It would have been easier to have done so at times of plenty. Hence the IMF’s rap on the knuckles. They have managed to weather the Great Recession, which did hit the developed world, and many have even promoted social policies, but none have implemented sufficient domestic reforms.

Nevertheless, although the growth of the emerging world’s stock markets is often like a roller coaster: since 1950 it has exceeded that of the developed countries by an annual average of 1.5%. Spain is keeping a close eye on this because, according to Goldman Sachs estimates, 26% of the sales of the IBEX-35 companies, the most highly exposed of the Eurozone, are precisely to those markets. A fair part of Spain’s future lies in the emerging countries.