The latest report on Global Economic Prospects by the World Bank paints a worrying picture: the emerging economies have stopped doing so, or at least they will do so much more slowly. This is not a temporary phenomenon but, according to Kaushik Basu, its chief economist and vice-president, a ‘structural slowdown’. It could have negative consequences for everyone and of course also for the developed countries because although they are growing today, they might very well run out of markets in which to expand. In fact, the World Bank has lowered their expectations of growth to 3.4%-4% (although the Eurozone has better prospects), while it expects the developing economies to grow by 4.7%-5.6%. This is significant, but a slowdown nevertheless, as pointed out more than a year ago by an IMF report. Bahnu Baweja of UBS notes in the Financial Times that if China were to be excluded, in dollar terms the growth of the emerging economies would be close to zero. Although with great differences between them, they are grinding to a halt.

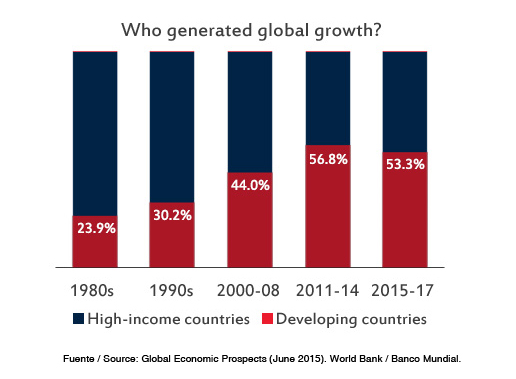

This is no return to the past. The world has changed. At the time of the Asian financial crisis of 1998, the emerging economies accounted for 32% of global GDP (in purchasing power parity). Now, following the Great Recession that began in 2007-08, they account for 53% and are essential for global growth. That is, the fate of both worlds is linked. It looked like the emerging economies would really emerge with the crisis, but despite becoming a alternative economic engine of growth, their torque was insufficient. They then fell into a ‘structural slowdown’, bringing back into fashion the concept that the economists call the ‘middle income trap’, that is, how certain countries stagnate upon reaching a certain level of development beyond which it is very difficult for them to go (although there are historical cases such as South Korea, and Spain many years ago, that are the perfect counterexample). The transition to a new harder economy for the emerging countries is spurred on by two factors noted by the World Bank: on the one hand, the higher interest rates promoted by the US Federal Reserve, which will increase the cost of credit for developing countries and hinder the vital influx of capital they need. On the other hand, there are lower oil prices, which are bad for exporters and not so good for importers, who are taking insufficient of the opportunity. To this should be added another pivotal factor: the generalised drop in commodities prices.

The BRICs are the key problem, but excluding India, which at an annual rate of 7.9% is the fastest growing big country. Russia is deepening its recession and Brazil is contracting. China (but not Asia, which is not doing all that bad) is at the centre of it all. Its growth has slowed down and it is importing fewer raw materials, to the detriment of the exporting countries. And perhaps it is even repatriating jobs. Its 7.1% growth forecast for 2015 and of 7% and 6.9% for the following two years remain important for it to continue rising to leading world economy status, but this is not enough to provide a sharp pull to other economies or even to encourage its middle classes, which may have an impact on its internal political and social stability.

The BRICs are the key problem, but excluding India, which at an annual rate of 7.9% is the fastest growing big country. Russia is deepening its recession and Brazil is contracting. China (but not Asia, which is not doing all that bad) is at the centre of it all. Its growth has slowed down and it is importing fewer raw materials, to the detriment of the exporting countries. And perhaps it is even repatriating jobs. Its 7.1% growth forecast for 2015 and of 7% and 6.9% for the following two years remain important for it to continue rising to leading world economy status, but this is not enough to provide a sharp pull to other economies or even to encourage its middle classes, which may have an impact on its internal political and social stability.

The World Bank’s forecasts point to something that has already been announced for some time: the end of the Great Convergence between developed and emerging economies that has occurred in recent decades. If confirmed, this will turn against the developed countries’ interests, as they need the emerging markets for their exports and investments. Some analysts see the possibility of an outright global recession, induced this time by the emerging economies as before it was by the rich countries.

The Great Convergence that might now be slowing down led to the rise of the middle classes in the emerging economies, while the crisis has made them become downwardly mobile in the developed countries. In some of the former, such as Brazil, there have been demonstrations by members of the new middle classes, who demand to be able to continue rising. In Europe, on the other hand, movements such as the indignados, for instance, have taken to the streets to demand an end demonstrated to demand a stop to their downward mobility. According to the OECD, in 2009 the middle classes numbered 1.800 million people, and its forecasts point to a total of 3,200 million by 2020 and 4,900 million by 2030, with Asia accounting for 66% of the total and for 59% of global consumption. Is this progression being jeopardised? If it is, the social and political consequences can be serious and highly destabilising.

Many emerging economies must change their production models. Too many of them have not put to good use the years of growth to leave behind the commodity exports trap. The recommendation of the World Bank’s chairman, Jim Jong Kim, is to invest in education, health and infrastructure and to create a more favourable business environment. But even if implemented, the results of reforms such as these could take years to bear fruit. And what is to be done in the meantime?