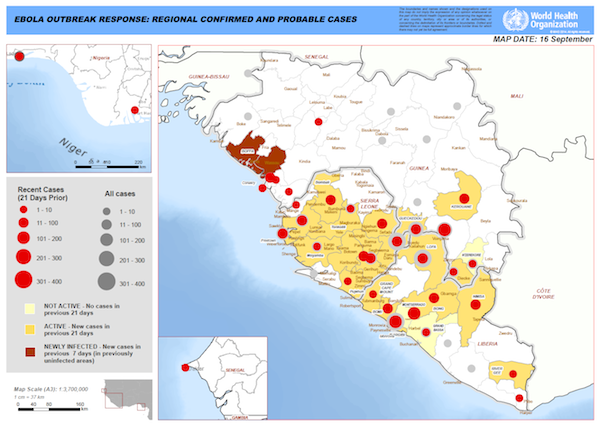

The international coalition against the Ebola epidemic is slowly being built upon the accumulation of mistakes made in the recent past. The number of cases in West Africa is growing exponentially –doubling every month— and now totals well over 3,000. Speaking at the UN, Barack Obama warned of the possibility of ‘hundreds of thousands of dead’ if the international community fails to act diligently –what is being done ‘is not enough’–, while calling the Ebola epidemic ‘a growing regional and global security threat’. A report from the Centers for Control and Prevention of Diseases (CDC) in the US warns that in West Africa (especially Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea) deaths from Ebola could reach the 21,000 mark in the near future, and even surge to 1.4 million in the most negative scenario, by the end of January.

There is a correlation between poverty and the rate of infection in these countries, as noted by Cristina Barrios in a cogent analysis for the EU Institute for Security Studies. There are already 15 countries at risk of contagion. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has established a roadmap to halt the Ebola epidemic within nine months, but with 20,000 more deaths and at a cost of at least US$1 billion. Its estimates probably fall short. The UN Security Council, unanimously and subsequently with the unprecedented support of 131 States, approved a resolution describing the Ebola epidemic in West Africa as a ‘threat to international peace and security’. The WHO’s Director General, Margaret Chan, has called it the ‘greatest peacetime challenge’ in UN history, while the World Bank has drawn attention to the ‘potentially catastrophic blow’ not only to the population but to the economy of these countries, to which it will contribute US$400 million. To this should be added the threat to political and social stability in these countries, where the population is increasingly mistrustful of the authorities’ handling of the epidemic.

Despite recent efforts, international organisations have done too little and acted too late. The NGO Doctors without Borders (MSF), whose volunteers are working themselves to the bone, has warned that the epidemic was well established before the WHO even sounded the alarm, and continues to claim that the help provided is insufficient and too slow. Obama has recognised ‘the failure of our international system to keep pace with an interconnected world. We have not invested adequately in the public health capacity of developing countries’.

Laurie Garrett, author of ‘The next plague: newly emerging diseases in a world out of balance’ (1995), claims that the health authorities knew that the Ebola outbreak was in the offing and also how to counter it, but did nothing. Not only were international contributions to the WHO’s budget not increased but following the financial and economic crisis that began in 2008 the extra-budgetary aid from rich countries –which were double the organisation’s budget– was reduced to almost nil, taking it back to its pre-1990 levels. Meanwhile, in 2011, Garrett recalls, the World Health Assembly, which controls the WHO, asked it to reduce its contributions to the fight against infectious diseases for the benefit of other non-transmissible diseases such as cancer and heart conditions.

The Security Council has called on UN countries to provide financial, political and medical support to limit the epidemic and to not interrupt air traffic to the countries involved. All commercial airlines have suspended their flights to the three most affected countries, thereby hindering the delivery of much-needed supplies. It is the Ghanaian government that has accepted the use of Accra’s Kotoka International Airport for the necessary airlifts in response to the crisis. The UN Ebola coordinator, David Nabarro, has noted that overwhelming action in the coming weeks might end the plague. But it is estimated that each patient requires the attendance of three health and logistics personnel. Hence, in order to ensure an adequate response a staff of three to four times the number of people infected would have to be in place ahead of events. What is required is an operation of military dimensions, and this is far from being the case at present.

Once again, the US has demonstrated its status as a superpower, this time against the Ebola epidemic. It has proved its worth as a scientific superpower too, as the CDCs have 15,000 employees and an annual budget of US$11,300 million, while the first experimental treatments have come from US laboratories. In the field, it is also the country with the best preparation and the greatest experience. Obama has ordered the dispatch of 3,000 troops to Liberia as part of an airlift consisting of doctors, nurses, medicines and hospitals, redirecting US$750 million –with more in the pipeline– from the Pentagon for these purposes. The US President –willing to lead, ‘but we cannot do it alone’– has called on world leaders to speed up the global response to Ebola, but many are dragging their feet. So far, the only ones to be fully committed are the US, the UK and France, which are in any case are also the most prone to military intervention, plus Cuba and a few others. The EU is again lagging behind, somewhat timidly. The African Union is becoming involved, but it has limited means.

Confronting Ebola has revived the idea of ‘containment’ that held pride of place in the West during the Cold War. However, in this case, to be successful it is necessary for the international community to act rapidly, concertedly and overwhelmingly. As reflected in the projections quoted above, time works in favour of the Ebola epidemic spreading and even in the best case this is a crisis that will get worse before improving.