The Islamic State (IS) is a practitioner of terrorism even more terrible than al-Qaeda as it has recently amply demonstrated. But that does not explain everything. It is also an insurgent movement and an army, and unless that is understood the strategy carried out by the US will fail. The movement has emerged in a sectarian conflict that has fed on a Sunni identity that is despised and penalised in Iraq and is in open rebellion in Syria against the Shiites. It is also expansionist, not limiting itself to a single territory in ancient Mesopotamia but aspiring to be present, either as a caliphate or a State, in Libya and elsewhere, in the process becoming a magnet for jihadists from around the world.

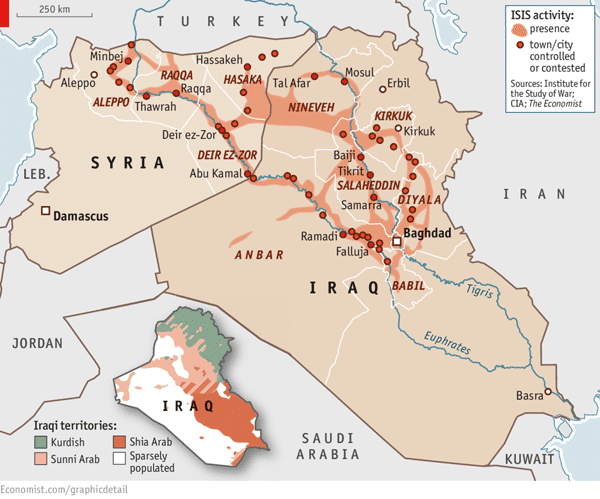

The US made a big mistake in Vietnam in not understanding that it was fighting against a nationalist rather than a communist insurgency. But what is insurgency? It is not only a revolt against the established order to replace it by another, but also a claim to a territory and an identity, in this case Sunni in addition to jihadist. Had this element been lacking, the Islamic State would not have had the clear support in some cases and the lack of opposition in others of the Sunni tribal groups that were denied power in Iraq (or who want to conquer it in Syria ) after the fall of Saddam Hussein and his replacement by a Shiite-dominated majority. Many of the IS’s cadres are former Sunni military from Saddam Hussein’s army. The IS has achieved its territorial gains based on these supports.

Many Sunni tribal leaders are supporting the IS which, despite relying on terror, brings a semblance of order and provides some sort of services. The same people who, for example, struggled in Anbar itself to dislodge al-Qaeda several years ago with US support later felt alienated by the predominantly Shiite regime in Baghdad. This also explains why the IS wants to be precisely a State, thus eliminating or changing the boundaries imposed by European colonialism.

Washington, whose strategy is still under construction, seems to have understood this time. Hence its insistence in getting rid of al-Maliki as Iraqi Prime Minister and to replace him by Al-Abadi and a more plural cabinet. But there is no guarantee that such a step will reassure the Sunnis. As noted by the expert Ramzy Mardini, the US cannot expect to attack those it sees as terrorists while pretending to stay on the sidelines of a sectarian conflict.

This is not a conflict that can be resolved only by bombing. If the US does not want to put its own boots on the ground, but rather put Iraqi –Shiite, Sunni and Kurd– and Syrian rebels in charge, the conflict will become complicated and last beyond the three years –since wars now tend to become prolonged– foreseen by the Obama Administration. He aims to whittle away the IS, starting by undercutting its sources of oil revenue (US$8 million/day, but how does the money, and the oil that generates it, flow?), reducing the territory under its control and ultimately defeating it.

Syria is not the same as Iraq. They are similar but not identical civil wars that require different approaches, as pointed out by Sydney Pollack, an expert who made the mistake of supporting the 2003 invasion. To begin with, Iraq has legal coverage since it has been its legitimate government that has requested intervention and that is not the case in Syria. Furthermore, in three years of civil war the opposition and local rebels in Syria have merely spread chaos, with a complete absence of civil administration or public services in the areas under their control. The IS has brought some semblance of order, although at the cost of a terrible repression. But what is clear from some reports is that the people are weary of and many would prefer a political solution.

But there is no political solution in the offing, either in the short or medium terms. Faced with an insurgency that is highly threatening, it is necessary to win the hearts and minds of the local population. It remains to be seen whether bombing, with its consequent collateral damage (civilian deaths), will not further alienate the local population. At least so far, the people do not seem to be turning against the IS in any numbers although there have been cases: local help assisted in the re-conquest of the cities of Haditha and Barwana.

Obama acknowledged in August that a military intervention that failed to re-establish a State would lead to chaos and new threats, as is occurring in Libya. Essentially, underlying the operation is a desire to rebuild a long-term policy in Iraq, with a highly decentralised system and a level of power for the Sunnis similar to that enjoyed by the Kurds. In Syria, where Assad can also take advantage of the situation, this is far more difficult. But in Iraq and in Syria everything hinges on resorting to the moderates. However, would such an attempt be viable?

The strategy must necessarily be based on more political considerations. If the conditions that made possible the emergence of the IS remain unchanged, little good will come even if it is defeated because it will simply be replaced by new groups.

Attacks are also being directed at other organisations, such as Khorasan and al-Nusra, which are supported by many thousands of Jordanians and Lebanese and are both linked to al-Qaeda. The other large-scale issue that remains unresolved is whether the IS’s terror campaign –including beheadings of westerners, as broadcast on You Tube– is actually seeking to provoke the intervention of the US or an international coalition. In any case, IS knows the images bolster their supporters’ enthusiasm and make them keep up with their competitors in radicalism.