It was brilliant idea to call it that, but the ‘cloud’ is not in the sky but very much on the ground, in servers that to a large extent (except for China, Russia and certain other powers) are located in the US. Internet is also subject to geography and geopolitics, and Snowden’s leaks about its use, or abuse, by the National Security Agency (NSA) and the cases of US espionage on Germany have led some governments to consider withdrawing some of the privileges afforded to the US by the fact that the Net was first set up there –as was the World Wide Web, despite being invented at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN)–.

Internet currently has around 3,000 million users worldwide. As indicated by a Pew Center report on the future of Internet, it is beginning to permeate almost everything: ‘The Internet will become like electricity – less visible, yet more deeply embedded in people’s lives for good and ill’. And it is not just the network that connects people, but it increasingly links machines in what is now called the ‘Internet of things’.

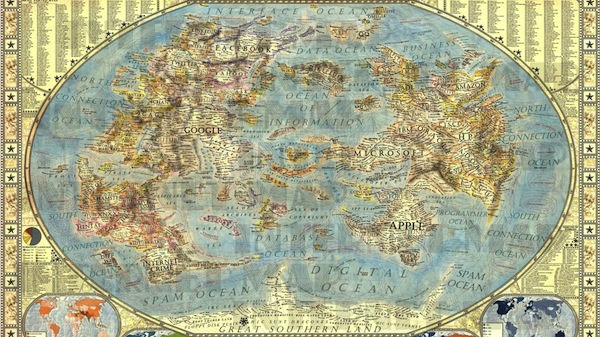

Of the 50 leading companies in the world of digital relations, 36 are American. A recent French Senate report says that the ‘Snowden earthquake’ has made Internet governance ‘a geopolitical challenge’ in a ‘new field of global confrontation’, with the consequent growing public concern for cybersecurity. Her irritation with US spying has led the German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, to propose the creation of a ‘European cloud’, an Internet system closed to US scrutiny, although much will also depend on the security surrounding it. She also proposes a European system for operating mobile phones, although its success would be more than doubtful without a large-scale company to back the project.

The French report criticises Internet’s ‘hypercentralisation’ to the benefit of large private players, the fact that Europe has become a ‘digital colony’ and other factors, including surveillance. It advocates that the EU ‘take in hand its digital destiny to make it a high-level political priority’ and that the proposal be promoted by the Franco-German axis. That is, it wants Europe to develop a new model of Internet governance in order to ensure its independence and democracy in this regard.

China has its own system, as do other countries, like Russia. But what these cases indicate is a move towards what the expert Daniel Castro calls ‘data nationalism’. In fact, countries such as Australia, France, India and Malaysia, among others, are beginning to approve national laws on data location, while there is the danger of Internet becoming fragmented if others follow the lead of China and Russia. At the NETmundial meeting in São Paulo in April, Brazil and Germany prompted a resolution on a multi-stakeholders’ Internet that did not please Washington. Brazil and Europe have announced a project to install a fibre-optic cable for Internet to prevent all the data traffic between the two continents going through Miami, where it is very easy to intercept.

Essentially, what arises from these geopolitical tensions over control of the Net is, as suggested by The Atlantic Magazine, the end of Internet as we know it: its balkanisation as a result of an increasing nationalisation and regionalisation that damages the interests of large US companies such as Google, Facebook and Amazon, which Europe lacks. These are geopolitical concepts adapted to a network that is based on independent and mostly private systems in which geography counts: although it has become open to other reliable countries, most of Google’s servers, for instance, are still in the US.

In the digital world, the US has an ‘exorbitant privilege’, to use the term that is usually applied to the dollar. In fact, it is from the US –from ICANN, a private partnership subject to the law of California– that Internet domain names are assigned. At a UN conference in Dubai in December 2012, Russia, China, Egypt and Saudi Arabia pushed through a proposal that Internet governance be taken over by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU, a UN agency), but the US and EU refused. Howeber, the EU is now reconsidering. In late 2013 it was Brazil and Germany –the two governments most affected by the ‘Snowden earthquake’, since it was revealed that both Merkel and Rousseff were under direct surveillance by the NSA– that requested the UN to adopt a resolution calling for the right to privacy in the digital age.

The French Senate report proposes that the EU take the lead in drafting an international treaty on the Internet that could also be subject to some form of online ratification by its users. Nevertheless, underlying this ‘digital diplomacy’ and its geography there are also national industrial policy considerations. In the background there is the question of ‘technological sovereignty’ that rests not only or mainly on the State, but also on firms and their capacity for innovation, even if in many cases they are supported by public action, as rightly explained by Mariana Mazzucato in her book The Entrepreneurial State. And in this field of innovation, Europe is lagging behind.