There are many who have held the belief that globalisation was a law of nature, like gravity. But it is not, and the events of the Great Recession should stand as a warning although, unlike in the Great Depression, there has been no collapse in a process that has not completed its recovery, even though worldwide connectedness has only discreetly recovered after its decline. This has been highlighted by the well-produced and informative DHL Global Connectedness Index 2014, which well deserves a rewarding browse. It is one of the few indexes that record a significant drop in the post-crisis level of globalisation, which nevertheless does not reach a negative conclusion but suggests that globalisation will be more global and less regionalised.

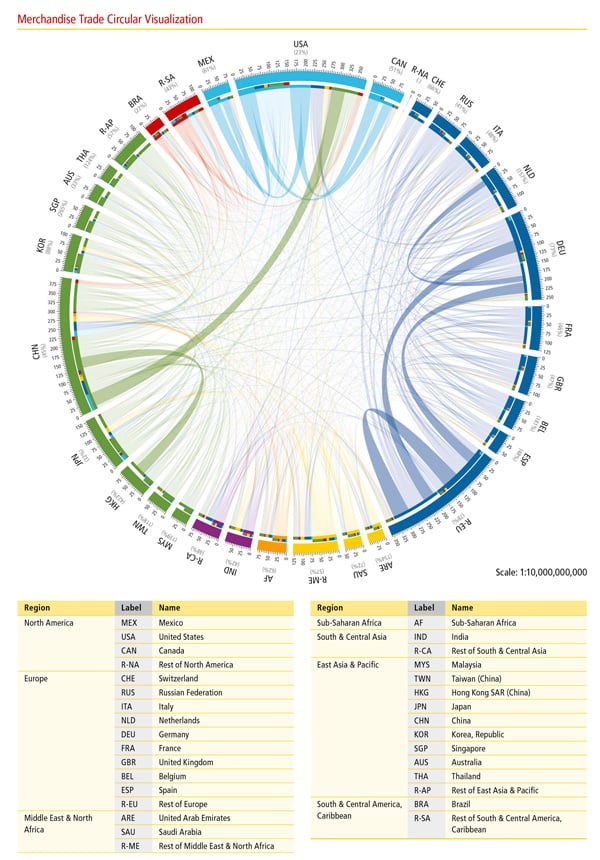

The analysis is based on three dimensions: the depth of exchanges and their geographical extent (breadth) and direction (outward or inward), based on 12 types of flows of trade, capital, information and people. The depth of globalisation has returned to growth again in 2013. As was to be expected, between 2005 and 2013 the movement of people has not increased much (from 3.1% to 3.4%). Borders continue to be a reality, although the report affirms that enormous economic growth would be possible if there were to be full freedom of movement of people in the world. The movement of capital has slowed down, in trade it has recovered following the decline of 2008-09 and in information it has skyrocketed.

The most connected country is the Netherlands, followed by Ireland, Singapore, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, the UK, Denmark, Germany and Sweden. It should be noted that nine of the first 10 are European. Indeed, Europe is the world’s most connected region (especially as regards trade and people), followed by North America (which is dominant in capital flows and information). The US is ranked 23rd, with Spain in 24th place, having climbed three positions in one year –with improved breadth but a decline in depth–. It was only in 2013 that Spain managed to regain the highest level of connectedness that it had reached in 2007.

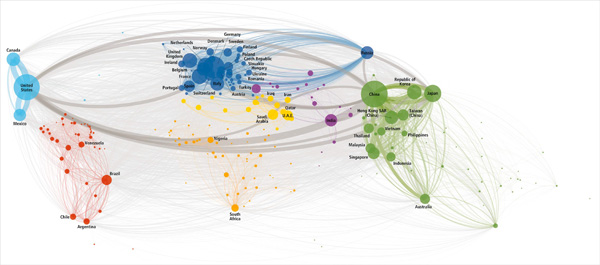

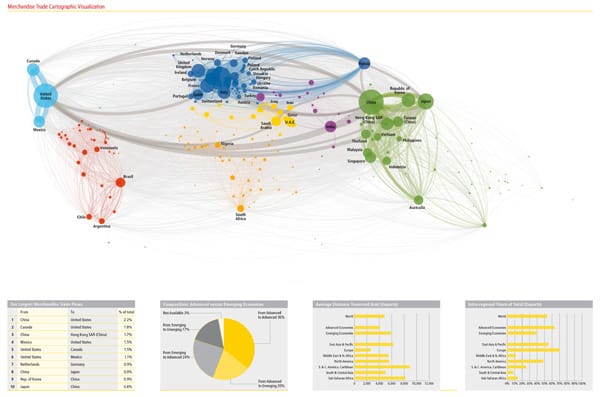

What is important, despite the Index being a ranking, is not actually its individual results but the major trends it reveals. The most important of the latter is that in recent years the advanced economies have been unable to match the rise of the emerging economies, limiting the breadth of global connectedness. The advanced economies have been unable to redirect their international interaction towards the emerging economies, partly due to differences and problems of culture, administration and politics, geography and economics. One consequence is that in 2010 up to 100 of the world’s largest companies that had their headquarters in advanced economies made only 17% of their total revenue from emerging countries, even though the latter accounted for 36% of global GDP and are projected to contribute 70% to global growth until 2025. The 10 countries in which global connectedness increased more between 2011 and 2013 were all emerging nations, although in terms of integration into the international flows of capital, information and people they lagged behind. Between 2011 and 2013 the highest average increases in global connectedness were recorded in countries of South and Central America and the Caribbean.

Although world regionalisation is much in vogue, the Index shows that flows have been growing in breadth, in distance, so that a trend towards the regionalisation of trade that has prevailed since decades ago was reversed between 2005 and 2013. That is, globalisation is in fact becoming more global. This can be seen, for instance, when analysing global Germany, for which the EU has decreased in relative importance, while the importance of China and Brazil has increased.

If the current crisis is overcome, the global economy could grow between 2014 and 2019 faster than in any of the previous three decades. What can de-rail this prospect is economic fundamentals but protectionist intervention, against which a company such as DHL which lives from and promotes connectedness has clearly taken a position.