‘Davos is a factory where conventional wisdom is manufactured’, according to David Rothkopf, Editor of Foreign Policy. But it frequently happens that this ‘conventional wisdom’ is simply wrong. Forming part of it are the forecasts of the World Economic Forum, which, nevertheless, are always of great interest. It is not only that their latest version, the 11th, of global risks, foreseen for 2016 and beyond –and not only individually but also interconnectedly– does not match reality but that the grandiose meeting at the famous Swiss alpine town has ended up by talking about other matters altogether. Predictably, talk has focused on the progress of the economy and the stock markets –although, since Frankfurt, Draghi has given them a certain respite–, on the worrying Chinese slowdown that is affecting both emerging and developed countries, and a drop in oil prices that is not only related to the above but that is beginning to be destabilising (‘irrational’, as described by Saudi Arabia) The IMF has, for the third time running in one year, downgraded its prospects for world growth, to 3.4% this year and 3.6% in 2017.

China, whose stock market crash marked the start of the year, announced last week that it is growing at ‘only’ an annual 6.9%. The rest of us would jump at the option, which implies that China provides the world economy each year with the equivalent of the economy of several G-20 countries. But there are two drawbacks: no one trusts Chinese statistics (many at Davos considered that China was actually growing at a rate of 4% or 5%, which isn’t that bad either) and, especially, the model is changing –from investment to domestic consumption–, while there are doubts about whether China’s institutions are adequate to manage the transition that requires jettisoning many traditional State enterprises. Davos has also reverberated with much talk about the dangers of the EU’s dissolution.

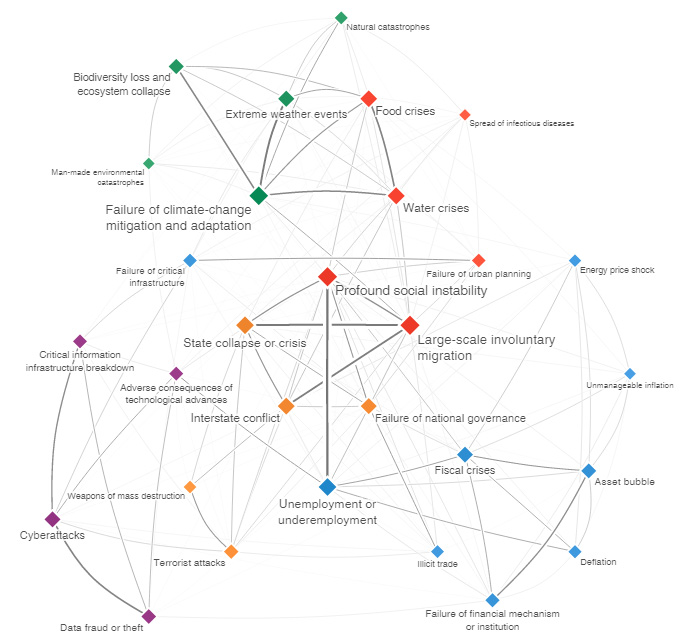

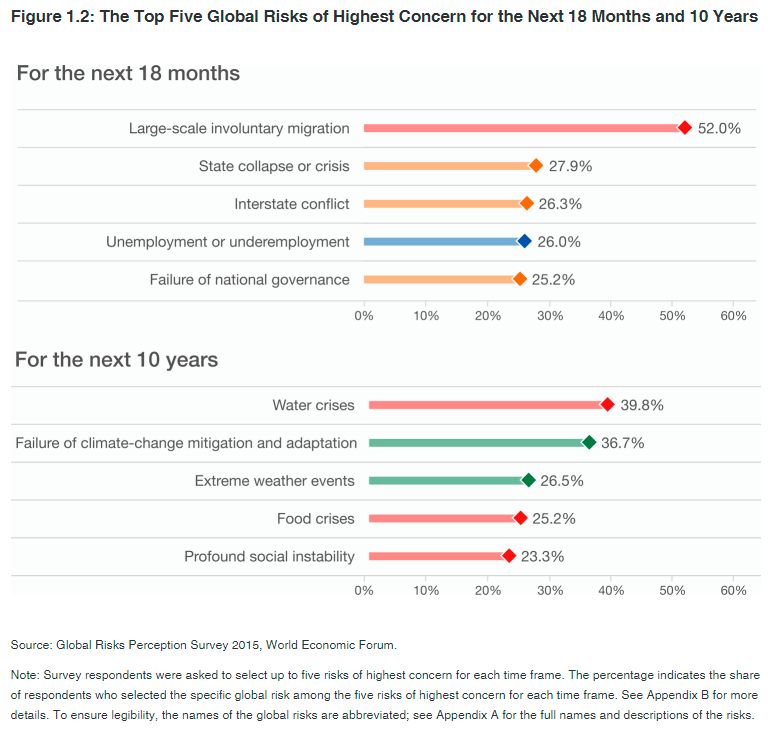

Nonetheless, contrary to previous reports, among the five major global risks in terms of their impact for 2016, only the last one is truly economic: a serious energy price shock. The others, from greater to lesser are: failure to mitigate and adapt to climate change, weapons of mass destruction, water-supply crises and large-scale involuntary immigration (which is, in fact, seriously undermining the EU). A further perspective for the next 18 months on the risks that most concern the experts consulted is variegated, including in order of importance: large-scale involuntary migrations, State crisis or collapse, interstate conflict, unemployment and underemployment and failed national governance.

In the longer term, with a 10-year view ahead, the perception of global risks is somewhat different, with the environment in a leading position: first, the water crisis, then the failure to mitigate climate change, extreme weather events, food crises and extreme social instability. The latter could be related to what was intended to be the star issue at the Davos forum, the fourth Industrial Revolution (resulting from the combination of Artificial Intelligence, robotics and not automation but the growing autonomy of machines and programs, 3D printing, nanotechnology, etc.). Another report by the Forum itself, titled The Future of Jobs, suggests that increasing automation and Artificial Intelligence could destroy up to 7.1 million jobs over the next five years (other studies’ forecasts are even more dismal) while there would only be 2 million new jobs. The outcome is that the Industrial Revolution 4.0 could destroy far more jobs than it creates. And the end result is far more serious: the disempowerment of the people, empowered to a certain extent by technology but lacking any control over decisions that affect them, thus leading to the risk of social instability.

The first of the reports devotes another section to security risks on a 15-year horizon (2030), explain that ‘transformative shifts in political and economic power –accelerated by technological innovation, social fragmentation and demographic changes– will profoundly alter the geopolitical and international security order’. That is to say, it is not only a matter of military or purely geopolitical questions. Security depends on many other factors. Even jihadist terrorism is not at the forefront. The report suggests three scenarios or future realities: a world made up of walled cities (‘gated communities’?), of strong regions and, as a third option, a major armed conflict that will reconfigure the world order. To counter them, it appeals to the ‘need for resilience’, ie, withstand attack and recover. The warning is clear: the gravest risks come from within societies themselves and from the effects of the action of human beings on nature.