In just a few days, a new global development agenda, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) will be approved at a UN Summit to be held in New York. These targets are meant to replace the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) that have shaped the international aid system for 15 years now.

The MDGs have been criticised over the years. They were accused, for instance, of reinforcing a North-South dependence logic, or of obviating important issues such as inequality or the economic and political dimensions of development processes.

However, this agenda was massively endorsed by the international community. And this was reflected, for instance, in a sharp increase of aid flows from traditional donors (that is, members of the Development Assistance Committee of the OECD) to developing and emerging countries. After a period of decrease and stagnation (following the fall of the Berlin Wall), ODA rose from less than 81.000 Million US dollars in 1990 to over 134.000 in 2014 (Graph 1).

Graph 1. Total net Official Development Assistance (ODA) from DAC donors (Million US dollars). Source: OECD

It has also shaped the way countries project themselves in the global arena. During the 2000s, development cooperation increasingly became a key element of countries external presence. This is revealed by the fact that, for traditional donors, aid boomed from 0.21% of DAC countries national income to 0.32% in 2001 only four years later (Graph 2).

Graph 2. Total net Official Development Assistance (ODA) from DAC donors (as a % of gross national income). Source: OECD

Despite the North-South logic that the MDGs agenda may entail there has been a huge transformation of the donors’ community over the last two decades. Prompted by the international shift of growth and GDP, several emerging countries are now relevant donors. This not only changes the aid landscape, it also contributes to transform the North-South logic behind the global development agenda.

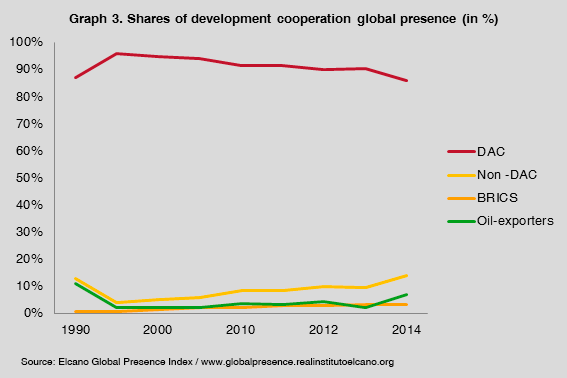

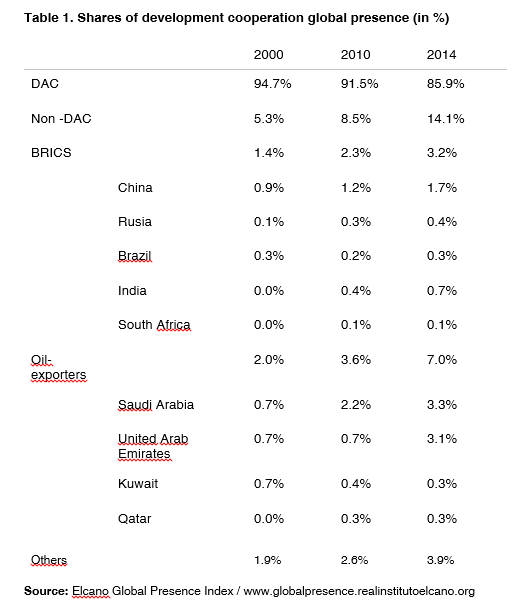

The appearance of emerging donors is reflected, for instance, in the results of the development cooperation component of the Elcano Global Presence Index. Graph 3 and Table 1 represent the shares of global presence for the aid component held by different groups of countries. In a ‘universe’ of global presence in the specific field of development cooperation, traditional DAC donors hold almost 86% of that presence. This figure contrasts with non-DAC donors share of global presence, which is little more than 14%. However, as shown in that same graph, the share of presence of traditional donors has been slowly shifting to emerging countries over the past 15 years.

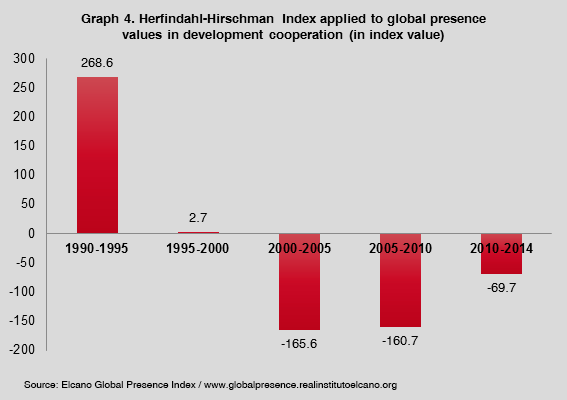

This trend is also reflected in the results of the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). The HHI applied to these global presence values calculates the degree of concentration of global presence in the particular field of development cooperation (Graph 4). Negative values indicate a process of de-concentration; a trend that started in the 2000. In other words, global presence in global development is being scattered among an increasing number of countries. This was, at least, the trend during the 2000s. It is worth noting that it has slowed down in recent years due to the economic crisis.

Another interesting feature of this de-concentration process is that among emerging donors, over the last four years, oil-exporters have been gaining weight over BRICs (Graph 3 and Table 1).

The SDGs are meant to adopt a global development agenda suitable for contemporary international relations. Among other issues, and given the emergence of new and diverse players in the donor community, this means that the new agenda needs to transform the North-South logic that prevailed in the MDGs. In this sense, the SDGs approach might be addressing this challenge as it levels the ground for all development players, with similar responsibilities and incentives for developed, emerging and poor countries.