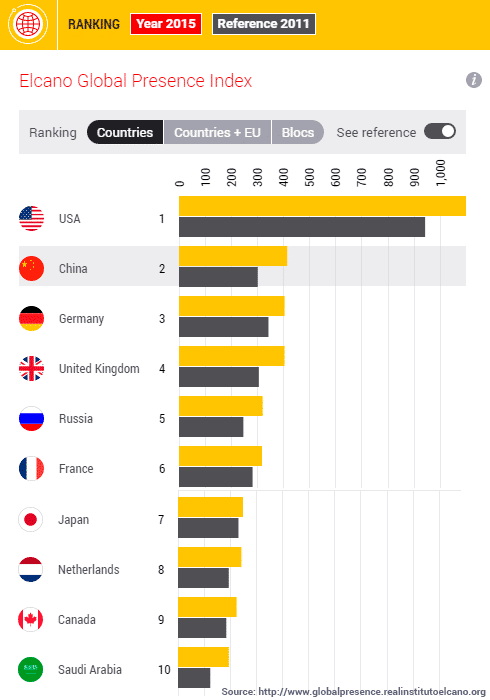

A country’s global presence, as defined in the Elcano’s Global Presence Index, is the aggregate product of a range of economic, military and soft variables. By measuring the external projection of a country –the extent of its international engagement– the Index provides a useful empirical basis to assess its influence in international affairs. The relationship between global presence and global power or role is, however, filtered by national interests and identities, political decisions and strategic choices. In other words, global presence is, at least to some extent, ‘what you make of it’. In this connection, the shifting patterns of the US and China are of particular interest, and of great consequence.

The US is still the country holding by far the largest and deepest global presence while China has jumped to the second place in the Index, overtaking Germany in 2016. However, the international outlook of the new Trump administration, as reflected in electoral statements and in the very controversial moves made since the president took office, and a range of key initiatives of the current Chinese leadership suggest that the two global powers will manage and steer their international presence in different ways in the years to come. The US may become a factor of regional and global instability and China may step in, acting and above all portraying itself as a pillar of stability. It is unclear whether the recent comments of China’s president Xi Jinping at the World Economic Forum, supporting globalisation and multilateral deals such as the Paris agreement on climate change, set a trend, but they sent a signal.

On the security front, President Trump has emphasized that the US will invest to preserve its military edge but de-emphasized support for allies, asking them to step up to provide for their security. He has called for a very tough approach to fighting Islamic terrorism as the principal threat to the US and questioned the Iran nuclear deal. A reinforcement of the American military posture in the Asia-Pacific may also be on the cards. In economic matters, the president seems determined to challenge trade deals and key partners based on a short-term calculus of what benefits the US can extract from them. On a broader level, ‘America First’ translates in a transactional approach to foreign policy, seemingly devoid of larger systemic or normative considerations.

In political and diplomatic terms, this agenda produces great uncertainty and risks polarizing the perceptions of and reactions to US global action. If translated into action, President Trump’s international priorities may suit strongmen from Russia to the Middle East but risk further antagonising public opinion in the Muslim world, confusing or alienating allies from Europe to Asia and heightening tensions with Iran and China. The withdrawal from the Tran-Pacific Partnership, the plan to build a wall between the US and Mexico (and to get the latter to pay for it) and the travel-ban on the citizens of seven Muslim-majority countries have already generated much diplomatic turmoil and affected the credibility of the US commitment to a rules-based, open international system.

China’s growing international presence makes of it a crucial global actor although to a different extent in different parts of the world. The balance of geopolitical and geoeconomic tools in China’s foreign policy changes depending on the region. China projects hard power much more assertively in territorial disputes in China’s neighborhood than in Eurasia, the Middle East or Africa, where economic interests and engagement prevail. That said, the picture is mixed, with economic links deepening across Asia alongside geopolitical rivalries and, conversely, China taking early steps to project its power in the Indian Ocean and beyond. China’s 2015 military strategy tasks the Chinese military with securing China’s interests abroad and the latter are ever-expanding. China has been scaling up defence expenditure for years and is building the first permanent naval base overseas in Djibouti.

However, Beijing has so far avoided getting involved in major political and security crises beyond its neighbourhood. Instead, it has used trade, investment and loans as tools for political influence. The so-called One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative, backed up by the large Silk Road Fund, is the primary example of this strategic approach. It aims to boost infrastructure, connectivity and value chains throughout Eurasia up to Europe, thereby expanding China’s political clout too. Meanwhile, China has both selectively invested in existing multilateral institutions, such as via UN peacekeeping or negotiations on climate change, and set up parallel institutional frameworks. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the BRICS New Development Bank and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation are cases in point, among many. In other words, China is leveraging its global presence through a variety of tools and channels, seeking to build the image of a responsible rising power.

Uncertainty prevails on the global stage. The first steps of the Trump administration indicate that the president has little qualms about altering or reversing traditional American priorities and commitments, thereby affecting relations with partners and challengers. Major domestic imbalances and mounting nationalism threaten to undermine the strategic webs and economic links that China is weaving. Much will also depend on how the two powers will deal with tensions in the Asia-Pacific. However, at the beginning of 2017, the scenario of an erratic US foreign policy generating instability alongside a more reassuring Chinese posture preaching restraint and engagement is not far-fetched. That would amount to the US punching below their global presence while China uses its international presence as an influence-multiplier.