Forty years ago this month, Spaniards overwhelmingly approved their new Constitution in a referendum which sealed the country’s transition to democracy. General Francisco Franco had died in 1975, after ruling Spain since 1939 following his victory in the three-year civil war.

Be it economically with, for example, the creation of significant number of multinationals or the world’s second-largest tourism industry in terms of visitors (81.8 million in 2017), politically with a vibrant democracy that ranks high in many classifications (one of the only 19 ‘full democracies’ in the ranking of the Economist Intelligence Unit), socially with the greatly improved status of women (11 of the 17 Ministers in the current government are female, the highest proportion in the world) or in foreign policy –where Spain has reclaimed its place on the international stage–, the country has been so profoundly transformed that for those who lived through this period, like this author, it seems like another planet today.

Per capita income at purchasing power parity has increased fivefold and average life expectancy at birth by almost 10 years, to 83 years, one of the highest in the world. Change has been deep too in the private sphere. The Franco regime lumped ‘pimps, villains and homosexuals’ into one criminal group. This year’s LGBT Pride parade in Madrid was led by Fernando Grande-Marlaska, the Interior Minister. Few countries have telescoped so much change into such a short period (see table).

Figure 1. 40 years on: Spain in a nutshell

| 1978 (1) | 2018 (1) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total population, million | 37.0 | 46.7 |

| Foreign population, million (2) | 0.17 | 4.7 |

| Per capita income, US$ (3) | 7,883 | 38,285 |

| Employment by sector, % of total | ||

| Agriculture | 20.3 | 4.3 |

| Industry | 27.4 | 14.0 |

| Construction | 9.5 | 6.0 |

| Services | 42.8 | 75.6 |

| Life expectancy at birth, years | 74.3 | 83.2 |

| Population aged 15 and under, % of total | 26.7 | 15.4 |

| Population aged 65 and over, % of total | 10.7 | 19.1 |

| Fertility rate, births per woman | 2.54 | 1.33 |

| Illiteracy rate, over 16s, % of total | 9 | 1.75 |

| University educated, % of over 16s | 3.6 | 28.2 |

(1) Or latest available.

(2) Excluding foreigners who became naturalised Spaniards.

(3) At purchasing power parity.

Source: William Chislett, Elcano Royal Institute.

The 1978 Constitution has given Spain institutional stability. There have been seven Prime Ministers since then (Italy has had 25); during Spain’s short-lived Second Republic, between the spring of 1931 and the summer of 1936, before the Civil War, the country had seven Prime Ministers and two Presidents. The comparison is even more striking if one takes the 21 years between the start of the reign of Alfonso XIII (1902) and the dictatorship of General Miguel Primo de Rivera (1923), when there were 33 changes of Prime Minister.

This transformation did not come from nowhere. The ‘economic miracle’ between 1960 and 1973, following the move away from autarky, which had proved disastrous, and towards liberalisation created a much larger middle class (33% of the population in 1970 compared with 14% in 1950) and with it a consumer society, ridding Spain of the huge gulf between rich and poor that existed before the Civil War and paving the way for reconciliation. In 1975, 74% of respondents wanted press freedom, 71% religious freedom and 58% trade-union freedom. The ossified political system under the Movimiento Nacional (‘National Movement’), the only legal political organisation, was out of step with the socioeconomic changes and people’s aspirations.

Democracy came incrementally rather than by engineering a swift and sudden break with the regime. King Juan Carlos, Franco’s successor as head of state under the restored Bourbon monarchy, used Franco’s laws to dismantle the regime. Ironically, the dictator thought, as he famously put it, that he had left his regime ‘tied up and well tied up’. The transition, however, was not guaranteed from the outset to be successful. It was achieved in the face of considerable adversity: the violent Basque separatist group ETA killed an average of 50 people a year in the first decade of democracy (and mounted assassination attempts in 1995 on both the King and Prime Minister José María Aznar), and right-wing Army officers staged a coup in 1981.

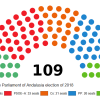

The face of Spain has also changed enormously. When Franco died there were only 165,000 foreigners officially registered in the country. That number rose to 800,000 in 1990 (2.1% of the population) and peaked at 5.7 million in 2012 (12.1%). To Spain’s great credit, the huge influx of immigrants has not produced any significant xenophobic, far-right movements or parties, making the country in this respect an exception to the norm in many other EU countries, such as the UK, France and Germany. Spain’s far-right Vox won a mere 0.2% of the vote in the June 2016 general election, but it won a worrying 11% of votes in the regional election in Andalusia this month. There are no French-style banlieues or US-style ghettos in Spain.

Today’s problems, such as the very high jobless rate, particularly among young adults, severe income inequality, increased social exclusion, the illegal push for independence in Catalonia and corruption in the political class do not detract from the fact that Spain has enjoyed an unprecedented period of prosperity and stability over the past 40 years.

Spaniards can be proud of what they have achieved, but the next decades will be very different. The challenges ahead will test this admirably cohesive society. The most visible one is the rapid ageing of the population and the pressure this is already exerting on the sustainability of the healthcare system and the viability of the state pension system. In 2050, 35% of the population is forecast to be over the age of 67 compared with 16.5% today. Within a decade, unless there is a significant demographic change, only around 400,000 people will be entering the labour market every year whereas up to 800,000 will be retiring annually. Such a change will put a heavy burden on public finances and weaken Spain’s economic growth.

Fittingly for the Constitution’s 40th anniversary, the process has begun to exhume Franco from his grandiose state-funded Valley of the Fallen monument and bury him elsewhere. This would have been politically impossible 40 years ago. Sufficient time has gone by during which Spain has become a mature democracy to finally resolve this contentious issue.