The Lowy Institute for International Policy has published the 2016 edition of its Global Diplomacy Index. This index calculates the number of diplomatic representations of each G20 and/or OECD country in the rest of the G20/OECD network, including embassies and high commissions (for Commonwealth countries), consulates, or representations to multilateral organisations. It could be said that this is an indicator of the diplomatic effort of countries.

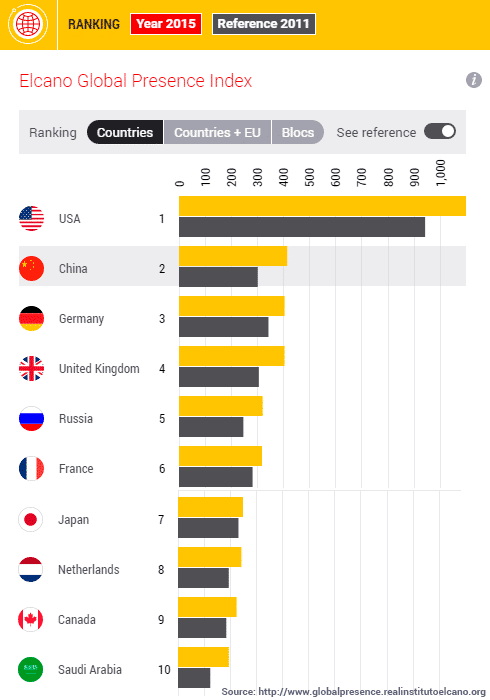

The Elcano Global Presence Index assesses the external projection of 90 countries (soon to be 100) on three economic, military and soft grounds. This combination of 16 variables includes varied forms of internationalisation such as manufacture exports, migrants, troops deployed, scientific performance or development cooperation. Means for foreign policy (diplomats, number of international representations…) are intentionally excluded, as the aim of our Index is to assess to what extent countries are ‘out there’ regardless their effort.

In short, Lowy’s Global Diplomacy Index deals with the means for foreign policy while, in a way, Elcano Global Presence Index assesses the results of this policy. Therefore, a comparison of these two indexes could throw interesting conclusions. For instance, it could show to what extent additional endowments lead to increased results (do countries with higher number of diplomatic representations record higher values of global presence?). It could also provide us with information on how ‘efficient’ external services are (are there countries recording comparatively high index values of global presence and ranking relatively low in the Global Diplomacy Index?).

However, firstly, the Global Diplomacy Index accounts the number of representations of countries in other G20/OECD countries exclusively, while the Elcano Global Presence Index assesses external projection anywhere outside countries’ own borders. It could be argued that, probably, for the particular case of these 42 G20/OECD countries, the lion share of such global presence is projected in other G20/OECD countries.

Secondly, most forms of external action considered in Elcano Global Presence Index are exerted by non-State actors (exports, investments, migration, culture, science, technology, sports). Moreover, some of them are only loosely linked to public action. Here too, it could be argued that regardless the stakeholder, one shared objective of countries included in the index is to extend global presence by any economic, social or political domestic actor.

Thirdly, a high ‘efficiency’ (global presence / global diplomacy) ratio –that is, high records of global presence using relatively scarce means of foreign policy– cannot be strictly interpreted as a measure of the quality of foreign policy. This combination can be due, for instance, to a large spending in foreign policy ‘at home’ (in headquarters). Also, taking the case of Iceland, a small island, geographical circumstances force a comparatively high number of external representations while limiting the volume of global presence (that correlates strongly with the economic and demographic size of countries). In a similar vein, the very particular geopolitical situation of Turkey determines an important international diplomatic deployment.

Having all those caveats in mind, we can draw very cautious conclusions of a very tentative comparison of the results of these two indexes.

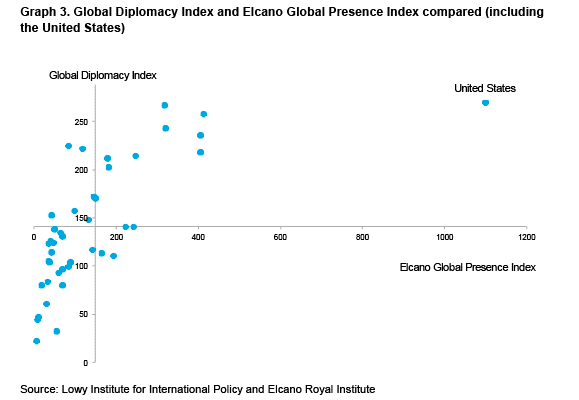

The first result is a fairly high correlation of 0.69 between 2016 data of the Global Diplomacy Index and 2015 records of the Elcano Global Presence Index. The average value of these 42 countries in the Global Diplomacy Index is 141 in 2016 and 149 for 2015 data of the Elcano Global Presence Index. However, in the latter case, this value is strongly determined by the United States record, that behaves as an outlier (Graph 3).

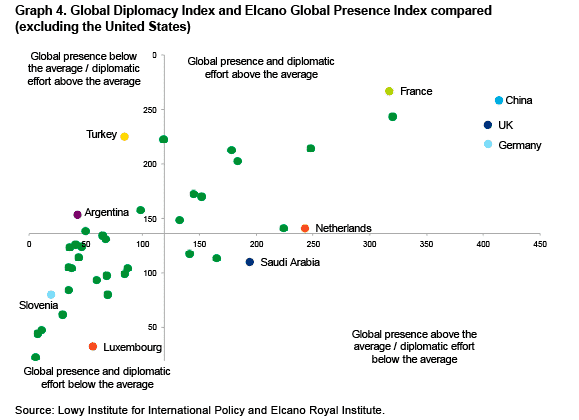

Excluding this outlier, those two averages decrease to 136 points for the Global Diplomacy Index and 119 for the Elcano Global Presence Index and, as a consequence, a good number of countries move to ‘more efficient’ zones (lower left and right quadrants of Graph 4).

Countries with the highest global presence – global diplomacy ratio are the United States (that ranks first in both indexes), Germany, Saudi Arabia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Meanwhile, nations with lower ratios are Estonia, Slovenia, Iceland, Slovakia and Argentina.

In a few words, biggest countries (in economic and demographic terms) project higher levels of global presence and deploy a greater number of diplomatic representations abroad (the reason why the Elcano Global Presence Index and the Global Diplomacy do correlate). Not all countries project the same amount of global presence with similar efforts in diplomatic representations. However, this does not imply, necessarily, that some countries are ‘better’ than others at foreign policy as a number of other factors, such as geography or geopolitical issues, are involved.