The new political reality has been evident now for some time. The world is changing, and so is Europe. The days of a permissive consensus are long gone and there are a number of political parties trying to exploit and capitalise on change. It is clear that in 2019 the race for office in EU institutions will be fiercely contested. There are already rumours doing the rounds about the names that will be competing for the top jobs –the presidency of the European Commission and the European Council, in addition to the presidency of the European Parliament (EP) and the European Central Bank–. Power politics in the Union, together with the never-ending South/North and East/West divide will be decisive in the selection process. In addition to the Union’s leading figures –of which I hope some will be women– there are a number of issues that are being closely followed in circles interested in European politics.

One of the most debated items on the list is the fate of the spitzenkandidaten –lead candidate– system. In 2014, when the process first entered into our vocabularies, there was a mutual understanding of –or a grand coalition for– accepting the candidate of the most voted group in the European Parliament as the candidate for the European Commission’s presidency. However, in 2019 it will not be enough to be the winner. The pre-condition for support is to be able to form a majority in the EP, which makes the matter even more complicated. As we know, this is a not-all-that-official deal between the European Council and the Parliament, as co-decision makers in the process of trying to secure a more democratic Union.

The candidates present an interesting picture. The election congress of the Party of European Socialists (PES) took place in Madrid this past weekend. The Congress elected Frans Timmermans as the Socialists & Democrats’ (S&D) spitzenkandidat, or lead candidate, positioning him as the most important rival of Manfred Weber, chosen by the European People’s Party (EPP). The third group, according to the polls, the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE) does not as yet have a lead candidate, mainly due to the current stalemate with Emmanuel Macron’s party En Marche, which has not yet decided to join the ALDE. In any case, the party will play a pivotal role in reaching a deal –some even consider it a kingmaker–. Michel Barnier’s name has also heard of as a compromise candidate in the Brussels bubble. In case of an institutional deadlock in the European Parliament, the European Council can appoint a widely acceptable candidate such as Barnier –especially if the Brexit negotiations come to a successful conclusion, which is very much open to discussion–. All these moves are yet to be seen and there is still a long way to go.

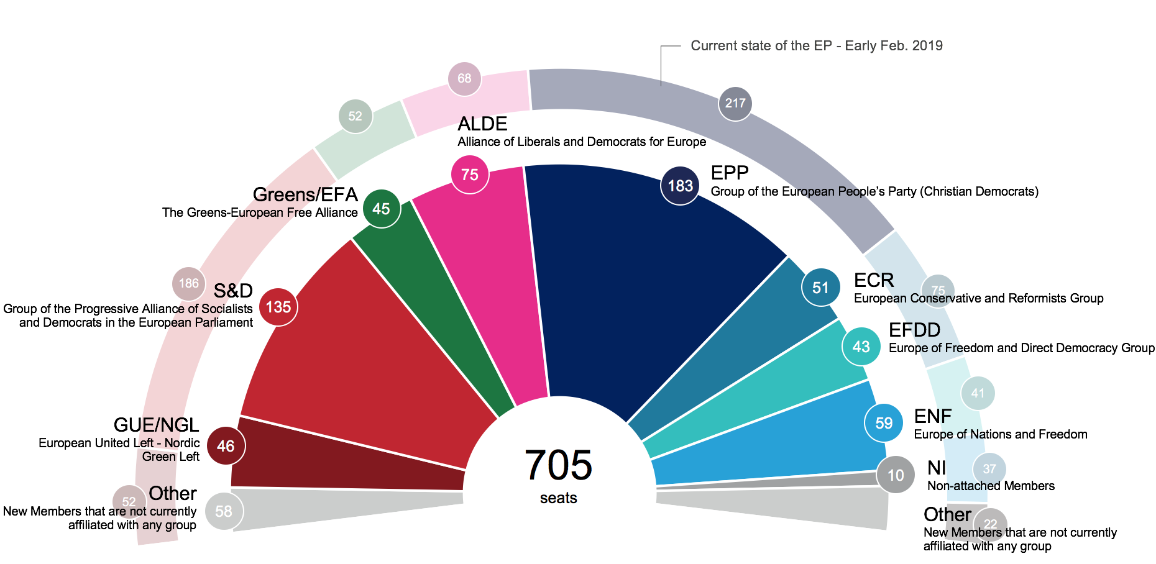

In any case, the lack of a grand coalition in the EP is also praised in various circles. The Parliament is expected to become more representative and more ‘real’, instead of being a relatively unconvincing example of a consensus culture. In a possible future scenario, the Eurosceptics are not expected to ‘swamp’ the Parliament according to the first seat projections of the EP itself. Expectations suggest that –despite polls being, of course, fallible– the EPP, S&D, ALDE and Greens/EFA will still gain more than 60% of seats in Parliament. The Eurosceptics, however, depending on whether they become members of an existing group or form their own, will still represent a significant voice for resisting any further deepening of European integration.

The rise of Eurosceptic parties in the EP is already receiving media coverage. However, it is not only the EP that we should be worried about. The European Council will be hosting various national leaders whose governments are either led by powerful Eurosceptic parties or shared by them. The case is similar in the European Commission. Since every country has one Commissioner, the supranational executive branch of the Union will have Eurosceptic Commissioners from Italy, Hungary and Austria –to name just a few–. This should create a new institutional dynamic, opening the way to further debate on important issues related to the future of European integration.

The Eurosceptics in the EP and in the Council are expected to be contrary to burden sharing (especially in issues related to migration policy) and will be up for stronger border controls. In addition, it is expected that they will mainly be against any further progress relating to the Eurozone, banking union or internal market. Moreover, bargaining over the Multiannual Financial Framework (2021-27) –usually known as the EU’s general budget– will be a tough battle. These are just some examples but there will be many other important decisions to come.

There are slightly less than 100 days to go for the elections to the EP and there is much at stake. The EU’s institutional set-up will have to adapt to whatever new balance will materialise. It is important to face up to reality and prepare for a new set of dynamics. Even if the times for a permissive consensus is over, the good fight for a more integrated, fairer and more representative Union will be the task for pro-Europeans, not as an idealised dream but mostly as a secure way to live in a more democratic Europe while the world is changing and multilateralism as we know it is increasingly falling apart.