The past two months have witnessed a variety of institutional responses to the recent developments in Turkey. To start with, on 9 November the European Commission published its annual progress report on Turkey as a candidate country, while the discussion on ‘how to “handle” this hot potato’ was included in the informal agenda of the Foreign Affairs Council held in Brussels on 14 November. According to both institutions, even if things have gone pretty bad, keeping the negotiation framework alive, and communication channels open, is the cleverest thing to do. On the other hand, members of the European Parliament (EP) voted a resolution for a ‘temporary freeze on EU accession talks with Turkey’ on 24 November. The resolution was approved by 479 votes to 37, with 107 abstentions. Even if it is a non-binding decision and the Member States have the final word, the message was crystal clear. Then, in December, the Member States gave their final verdict: ‘The full respect of commitments and established conditionality in accession negotiations will contribute to EU-Turkey relations achieving their full potential’. All these different European responses, which would be even more diverse were each Member State looked at it greater detail, require further analysis.

What has been going on in Turkey – according to the European Commission?

The European Commission’s Turkey 2016 Report was far more critical than in previous years. The word ‘backsliding’ has frequently been used while focusing on the rule of law and freedom of expression. The concerns related to the detention and arrest of several members of the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), including the two co-chairs, have been clearly underlined. The report has also provided a full summary of the suspensions, dismissals and arrests that took place after the attempted coup. According to the report, as of the end of September 2016, some 40,000 individuals have been detained and more than 31,000 remain under arrest, including 81 journalists. Meanwhile, 129,000 public employees remain either suspended or have been dismissed and over 4,000 institutions and private companies have been shut down. The report also questioned the criteria applied and evidence used to determine alleged links to the attempted coup and terrorist activity, querying whether they were transparent and non-discriminatory. The process has also led to the closure of media outlets and newspapers, including Cumhuriyet, one of the oldest, most critical and popular newspapers in the history of Turkish Republic.

As for the usual framework of accession negotiations, 16 chapters have been opened and only one has been provisionally closed. On the other hand, cooperation in the areas of joint interest –most importantly the fight against terrorism and irregular migration– continued in line with the conclusions of the EU-Turkey Summit of November 2015. The visa liberalisation roadmap, with possible visa-free travel being the most concrete contribution to Turkish citizens’ lives, is said to be still on track, awaiting the attainment of the remaining benchmarks by the Turkish government. In short, the European Commission’s document provided its summary within the framework of accession negotiations. This year, for the first time, the framework was accompanied by the EU-Turkey statement of 20 March.

The position of the European Parliament, the only directly-elected institution

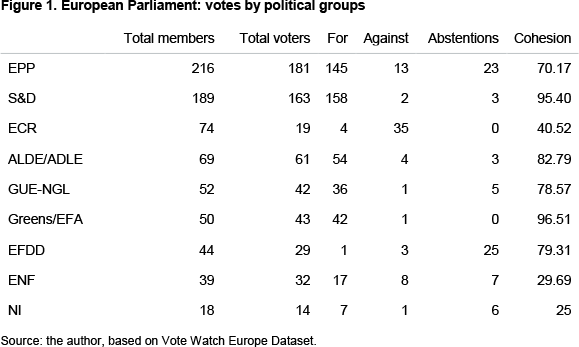

The members of the European Parliament (EP) voted on a resolution for a ‘temporary freeze in EU accession talks with Turkey’. As mentioned above, the resolution was approved by 479 votes to 37, with 107 abstentions. Despite being a non-binding decision, the message to Turkey was very clear. Figure 1 shows the votes by political group in the European Parliament, bringing into relief the sharp differences between them.

The groups are ordered according to their size, starting with the biggest group: the European People’s Party (EPP). As shown in Figure 1, the decision to vote for the resolution is very common among all political groups. However, in the Eurosceptic group of Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD), which is led by politicians from UKIP and Alternative für Deutschland and includes Movimento 5 Stelle, there were many abstentions. It is a very ironic point to underline, since these political parties constantly use Turkish candidacy as a tool for anti-EU propaganda. Another political group to look at is the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR), who call themselves ‘euro-realist’. Even though a deeper analysis of this vote is beyond this paper’s scope, the importance of realpolitik in decision-making should always be borne in mind, even if the final decision is a strong message to Turkey.

Realpolitik still dominates the positions of Member States

On 14 November the EU’s 28 Foreign Ministers met in Brussels to discuss the Union’s relations with Turkey, in addition to their agenda on common foreign and security policy and global strategy for the EU. Once the Foreign Affairs Council Meeting was concluded the message was clear: the partnership with Turkey in security and migration management is very important. Although Austria’s Foreign Minister Sebastian Kurz reiterated his call to halt accession talks with Turkey, he failed to obtain enough support from his co-ministers. The declarations of Federica Mogherini, the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and Vice-President of the European Commission, on the latest developments in Turkey and her remarks at the press conference after the summit were clear signs of concern, but still, there was not enough political will for a substantial move, at least for now. A very similar situation was repeated in December as expected, underlining the importance of commitment to the process and common goals. The declarations after the summit underlined the fact that Turkey is a key partner in various dimensions and that its commitment to the partnership should continue. In short, the representatives of the Member States, the Union’s intergovernmental front, have been avoiding making any dramatic moves regarding Turkish-EU relations.

Even if there is an institutional dispute some things on the list are very clear

The institutional division between the European Parliament, the Commission and the Council regarding Turkey has become even more visible over this period. Both Member States and institutions are divided on the steps that are required to be taken. There are three main considerations that are halting any dramatic rupture:

- The highly-criticised EU-Turkish refugee deal and the fight against illegal migration. This has been ‘the’ issue on the European agenda for 2016.

- The fight against terrorism. With the election of Donald Trump as US President, Europe will have to rely more on itself and on its bilateral relations in terms of its foreign and security policies.

- The reunification of Cyprus. Turkey is an important player on this front and its contribution to the process for a positive outcome in very advanced negotiations is extremely important.

Trade relations and all the other economic ties could be added to the list. For these reasons, no dramatic gesture should be expected, at least for now. Still, one thing is also very clear: further statements underlining how worried EU officials are, are most certainly very unwelcome by even the most Europhile citizens of the Turkish Republic, when taking into consideration the country’s public opinion. On the other hand, there is also a very tough electoral calendar facing the EU. France, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands, four out of the six founder-members, will be going to the polls in coming months. Hence, their governments will attempt to avoid any problems with Turkey in order to protect themselves from any issues related to the refugee agreement, which might cause an increase in refugee flows to Europe right before the elections. It is also known that populist parties will use any migration-related issues wisely. Taking all into consideration, even if the current situation in Turkey is very alarming –maybe even more than ever– no dramatic rupture is likely.

The EU is, in any case, moving towards a new model of differentiated integration. It is safe to claim that there will be a new offer for Turkey in this new structure in the near future. All this will be discussed right after the critical elections to be held in Europe next year.