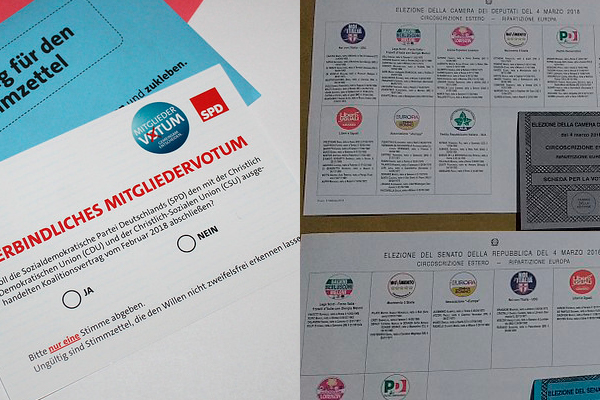

This Sunday, 4 March, the whole of Europe will be awaiting news of two poll results: the verdict of Germany’s Social Democrats on the pact with the Christian Democrats to form a new Grosse Koalition (known as GroKo), and the Italian general election. The EU has plenty at stake in both.

The SPD-CDU/CSU pact, which styles itself a ‘treaty’ (no less), calls for ‘a new awakening for Europe. A new dynamic for Germany. A new unity for our country’. It includes a detailed plan for EU development that partly coincides with Emmanuel Macron’s. If the coalition efforts founder, Angela Merkel will have to settle for a minority government, which will be weaker, or fresh elections, which would set this ‘new awakening’ for Europe back.

The Social Democrats who are most opposed to the deal –spurred on by Kevin Kühnert from the youth ranks, or Jusos– base their animosity not on opposition to Europe, but on a fear that it writes the death warrant of the SPD and because they do not want to allow the eurosceptic Alternative for Germany, AfD, to become the largest opposition party. But after the failed attempts to build a coalition between the Christian Democrats, the Greens and liberals –the latter with a different vision of European integration– the agreement between Merkel and her allies and the Social Democrats –whether as part of the government or with promises of support on specific issues from the opposition– is the only way to avoid an uncertain election. It would be uncertain because the coalition attempts have already taken their toll: various polls suggest that, in a new election, the combination of the CDU/CSU and the Social Democrats would no longer command a majority. Germany would become less pro-European. In any event, if the SPD grass roots endorse the deal, it will be Merkel’s last government. The appointment of a new CDU secretary general is a first step.

Meanwhile, Italy is voting with a new electoral system, the real impact of which is unknown. As Emmanuel Rivière and Arno Husson argue at the Centre Kantar sur le Futur de l’Europe, the Italian election is being held in the shadow of a threefold crisis: the economy, immigration and local, national and European representation. But these are crises that are present in many European countries, despite the economic recovery. In Italy, with the third largest economy of the 27, the issues at stake in this election are ones being debated throughout the EU: sovereignty, austerity and doubts about the kind of Eurozone that is needed, restrictions on immigration, regional concessions, etc. And this comes at a time when the EU has suffered a notable loss of popularity, in a country that for many years embraced it as part of its essence. It is not, however, europhobia that is winning (yet), but euro-apathy, if the French concept of morosité may be thus translated. Nevertheless, the stock market in Italy has seemed calmer than in other parts of the EU and the world.

There is a fear in Europe of advancing too fast, thereby providing the eurosceptics with an even greater boost. Although headway is being made in certain areas –finally embarking on strengthened cooperation in defence, for example, and modernising if not increasing the EU budget, despite the setback represented by Brexit –a degree of retreat is evident in the general idea. The President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, supports the idea of Spitzenkandidaten (candidates put forward by the political groupings in the European Parliament) for determining his successor, a system whereby he himself emerged after the most recent European elections, and which enjoys greater legitimacy than direct appointment by the European Council. He has also proposed merging the posts of Commission president with the president of the European Council. He has on this pretext been accused of nothing less than supporting the idea of a European ‘superstate’, a United States of Europe. The European Council, meeting informally in Brussels last week (without the British), defended its prerogatives tooth and nail. It wanted no truck with the automatic recurrence of the Spitzenkandidaten and rejected out of hand the merging of posts. All steps in the direction of federalism have been thwarted.

Rather than redistributing the British seats post-Brexit to a transnational list that would have been very attractive from a pro-European viewpoint –and had been advocated by Macron– the European Parliament has chosen to reduce the 705 seats and distribute some among member states that had been underrepresented in previous arrangements. Spain will thus gain a further five seats in the parliament. This makes up for what was not obtained under the Lisbon Treaty when the Spanish negotiators focused on presence in the Council rather than seats in the European Parliament, despite the advances made on joint decision-making achieved between the two institutions.

Despite, or thanks to, Brexit, Europe is making progress, but is trying to rein in any talk of federalism, if that is the right word, and generally avoid referring to the political dimension of Europe. It is trying to focus on people’s concrete problems, admittedly so far without great success, despite the new economic growth. Both Macron and Merkel have plans for the greater integration of the monetary union, albeit not entirely overlapping. Europe is on the move, but it does not know where it is heading. Or rather it knows where it does not want to go: towards federalism (although the Eurozone is advancing discreetly towards it). The expression is taboo. There is also a lack of storytelling, a narrative that explains the EU’s evolution. The europhobes have contaminated the national and Europe-wide discourse of the europhiles, fearful of losing votes on this issue. These are internal problems particular to each (often similar), making it difficult to provide a general definition, and are in addition to the conflicts of national interest. There are also too many differences between countries, frequently going to their very core; for instance, between Spain, Poland and Finland. While Darwin showed that evolution in nature does not have a direction, institutions built by human beings usually exhibit it. Even if the coming Sunday turns out well (‘well’ in a pro-European sense), the ideological and practical limits of this debate will be laid bare.