The ruling neo-Islamist Justice and Development Party (AKP) of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan recovered the absolute majority in Turkey’s snap parliamentary election that it lost in June, but with not enough seats to push through constitutional reforms to enable him to become an executive president.

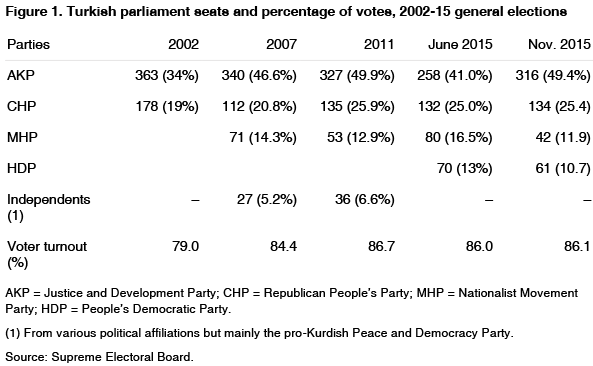

The AKP, in power for the last 13 years, won 316 of the 550 seats, up from 258 in June (18 short of a simple majority). It needed to gain 367 seats to unilaterally impose the presidential system that the autocratic Erdoğan so fervently desires.

Erdoğan called a fresh election after his party could not muster support for a coalition government –which it half-heartedly tried to negotiate–. This was a gamble and it handsomely paid off for Erdoğan, whose political instincts are second to none.

“Erdoğan turned up the heat on the opposition media, even closing down a TV channel while it was on the air”

A deeply divisive figure, Turkey became even more polarised during the five months since June’s election as war resumed between the Turkish state and the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) after a two-and-a-half-year ceasefire ended; a suicide attack on a rally held by the pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP), attributed to Isis, killed 102 people, and Erdoğan turned up the heat on the opposition media, even closing down a TV channel while it was on the air.

It was the HDP that deprived the AKP of another absolute majority in the June election, as it surpassed the abnormally high threshold of 10% (3% in Spain) of the vote required to win seats in parliament. It got 13% and became the first pro-Kurdish party in Turkish history to gain representation in parliament (as opposed to Kurds in other parties). Had the HDP won fewer than 10% of the votes, its seats would have been forfeited and gone to other parties, which would have given the AKP its absolute majority in June. This time the HDP only just scraped through the 10% barrier, losing in the process 29 of the seats it had won in June (see Figure 1).

“ Erdoğan again broke the spirit of the constitution by campaigning heavily for the AKP”

Erdoğan, three-time Prime Minister and since 2014 the country’s first directly elected President, again broke the spirit of the constitution by campaigning heavily for the AKP. According to the constitution, the President is a non-partisan figure barred from any links with political parties once he takes office.

The AKP’s agenda of strong leadership, security and stability struck a chord with the electorate and enabled the party to win votes from the far-right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) –which lost 38 seats– and probably pious Kurds from the HDP. The MHP lost a quarter of its vote. The AKP won 5 million more votes than in June. The Republican People’s Party –established by Kemal Mustafa Atatürk, the founder of Turkey’s Republic in 1923 on the ruins of the Ottoman Empire– stood still and almost repeated its June results as the main opposition. The results showed that Turks, refuting opinion polls that predicted similar results to June, did not want a (probably squabbling) coalition government. There were five such governments in Turkey between October 1995 and November 2002 before the AKP came to power.

“Erdoğan was also indirectly helped by the EU’s decision to delay publication of its annual report on Turkey’s progress in its bid for membership”

Erdoğan was also indirectly helped by the EU’s decision to delay publication of its annual report on Turkey’s progress in its bid for membership. The report, normally released in October, would have continued to be critical of Turkey’s record in the sphere of the rule of law, the lack of media freedom and human rights issues. The report would have given ammunition to Erdoğan’s opponents. The EU’s decision was viewed in some quarters as showing Ankara’s leverage over Brussels at a time when it wants to enlist Turkey’s cooperation in efforts to stem the tide of migrants and refugees entering Europe. Turkey currently has around 2 million refugees from its war-torn neighbours, mainly from Syria.

Angela Merkel’s visit to Istanbul last month was also a gift to Erdoğan. The two of them were photographed sitting on gilded armchairs with pseudo-Ottoman decorations.

The AKP won the election freely but not fairly. Adored by his supporters and hated by his opponents in equal measure, Erdoğan is not a man who takes to any form of criticism of him lightly, be it on the social media (see Figure 2) or in newspapers, radio and TV. Freedom House, the US-based democracy group, has rated the Turkish press as ‘not free’ since 2013, when the government suppressed mass protests. Turkey’s press freedom score dropped from 54 in 2010 to 65 in 2014 (0 = best; 100 = worst).

Erdoğan faces a deeply divided country, and with a serious risk of the renewed fight of the PKK returning to the full scale war with the state that characterised the 1990s.

Having ramped up his nationalistic rhetoric since June, he should reach out to the HDP, now that it is in parliament, as the conduit for resolving definitively the Kurdish problem. After all, Erdoğan has done more than his predecessors to end the problem, pulling back when he thought it would spoil his electoral chances.

Now that he has almost got everything he wants, and behaves as if he was an executive president in all but name, he should be magnanimous with his victory and towards his enemies.