The victory of Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey’s prime minister for the last 11 years and an increasingly authoritarian and polarising figure, in the first round of the country’sfirst presidential election by popular vote, marks a significant turning point in the political life of a nation that has been a sluggish EU candidate since October 2005.

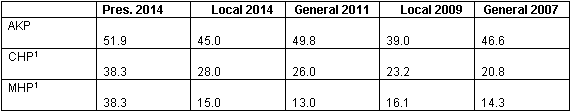

Erdogan won almost 52% of the vote compared to 38.3% for Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu, the unknown and former head of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, who was the joint candidate of the centre-left Republican People’s Party and the right wing National Action Party, and 9.7% for Selahattin Demirtas of the pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (see Figure 1). Voter turnout at 73% was much lower than the 90% in April’s local elections, but the AKP’s share of the vote was the highest it has yet achieved.

AKP= Justice and Development Party; CHP= Republican People’s Party; MHP=Nationalist Action Party

Source: Supreme Electoral Board.

(1) Joint ticket in the presidential election along with some other parties.

No one expected Erdogan to lose least of all the hubristic leader. The Islamist-rooted Justice and Development Party (AKP), the only nationally-based partyand one that has empowered pious Turks in the rural heartland, has a won the last six general and local elections andtwo referendums. Under the AKP, per capita income has tripled and infrastructure transformed with mega projects: the 533km high-speed rail between Istanbul and Ankara (the trains were made by Spain’s CAF) was inaugurated in July.

The choice of the 70-year-old Ihsanoglu, a diplomat and scholar of Islam, to represent the forces loyal to the secular republic founded by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in 1923 showed just how much the political landscape has changed in Turkey under the socially conservative AKP which never tires of seeking to micro manage people’s lives. In the latest outburst, Bülent Arinc, the deputy prime minister, declared that it was unseemly for women to laugh out loud in public. This was no laughing matter for Ihsanoglu who responded by writing on Twitter, “We need to hear the happy laughter of women.”

Erdogan and his formidable electoral machine pitched the election as a battle between the ‘old guard’ secularist elite and a ‘new’ Turkey. ‘No one has lost this election – except the status quo,’ he said in his victory speech. His campaign slogan was ‘national will, national power.’

The post of president (previously elected by parliament) is largely ceremonial, although under Turkey’s existing laws the president has the authority to call parliament, summon Cabinet meetings and appoint prime ministers and some high court judges (powers that Erdogan would not hesitate to use).Erdogan will now seek to change Turkey’s constitution in order to enshrine it with strong US-styleexecutive powers. This would enable him to continue to run roughshod over the rule of law and checks and balances. The illiberal constitution was drawn up in 1982 under the tutelage of the military after it staged a bloody coup. There is no doubt it needs changing in many aspects, particularly in order to comply with EU norms that Erdogan flaunted when he was prime minister, but not in order to give Erdogan the kind of free rein he had as president.

Access to YouTube and Twitter was blocked for a time earlier this year when the authorities tried to crush a corruption scandal that involved Erdogan’s inner circle; several thousand police officers, judges and prosecutors pursuing the corruption

cases were dismissed or transferred; the police brutally suppressed the protests over Gezi Park in Istanbul and those by the bereaved family members of 300 miners killed in a fire in a coal mine, and in its most recent report (2013) Reporters Without Borders downgraded Turkey to 154th out of 180 countries in terms of media freedom (95th in 2005). Most of the media exercises self-censorship and is pro-government. Erdogan was given a disproportionate amount of the airtime.

Erdogan saw the corruption probe as orchestrated by his former ally turned arch enemy, the US-based cleric Fethullah Gülen, whose followers known as Hizmet are influential in the police and the judiciary. Erdogan was happy to let Hizmet serve his cause to weaken the military by producing fabricated evidence and violating due process in the Sledgehammer trial that led to the jailing of 237 retired army officers in 2012 accused of plotting a coup. Once fully behind the charges, the fall out with Gülen led the government to concede that there was a plot against the military. The Constitutional Court released all the officers in June 2014.

The very detailed account of the Stalinist-style trial by the Princeton University professor Dani Rodrik, the son-in-law of General Çetin Doğan, the alleged and freed leader of the coup, is devastating.

Erdogan, like Vladimir Putin, has a majoritarian concept of democracy, reinforced every time he wins an election.The AKP has so far failed to reform the constitution to empower the presidency as it does not command the support of two-thirds of members of parliament needed to do this. It will try again after the next general election, scheduled for 2015 but which could be brought forward.The AKP has mooted the idea of changing the electoral law to create narrower constituencies, which would probably give it more seats, and lowering the threshold of 10% of the vote needed for a party to win seats in parliament (5% in Spain). This would benefit pro-Kurdish parties with whom it could then make a deal to reform the constitution.

A key pointer to Erdogan’s style in the presidency will be the formation of a new government, particularly the person who takes over from Erdogan as prime minister and hence head of the executive branch. The less autocratic Abdullah Gül, the outgoing president and co-founder of the AKP along with Erdogan, ruled himself out for the post in April in a job swap similar to that of Putin and Dmitry Medvedev, but he later left the door open.

Meanwhile around half of the 35 EU accession chapters remain either blocked because of French and Cypriot objections or frozen by the European Commission because of Ankara’s failure to implement the 2005 protocol and open its ports and airports to Greek-Cypriot traffic and hence extend its customs union with the EU (since 1996) and recognise the Republic of Cyprus, an EU country since 2004.Cyprus has been divided since Turkey invaded the island in 1974 and occupied the northern part of the country.

Only one chapter has been opened in the past four years, and the prospects for further progress and establishing a genuine liberal democracy with Erdogan believing that only he and the AKP embody the ‘national will’ are not promising.