English is deeply rooted in the institutions of the EU and this is not about to change, whether Brexit finally comes to pass or not. The first reason is that, even though some commentators in Spain and beyond who are irritated by Brexit, including a celebrated Spanish cartoonist, may be unaware of it, the Republic of Ireland and Malta –which have English as their official language (plus Gaelic in the case of the former)– will continue being member states, and English therefore an official language of the EU. But, above all, because English has become the lingua franca in Brussels (and the world), and will continue being so.

In the European institutions, particularly in the Commission, French predominated at the outset. The entry of the UK, Ireland and Denmark in 1973 did nothing to change this. It was essentially French that continued to be spoken and used in working documents (the official documents had to be available in all languages) and in press conferences. It was in 1995 that the situation truly changed, with the entry of Sweden, Finland and Austria. Suddenly English began to prevail in a plethora of meetings, reports and even the Commission’s famous salle de presse, because the emissaries of these new members –their civil servants, journalists and so on– spoke decent English but were largely ignorant of French. In the interim, English –international English at least, which is not exactly the language of Shakespeare–, thanks less to the UK than to US influence and its flexibility, had already become the language of globalisation. And with the accession of the Eastern European states (as well as Cyprus and English-speaking Malta) from 2004, a generation had already been learning English, which they rapidly assimilated to the detriment of Russian. Despite the inroads that have made by English in the Baltic States –where there are still significant Russian populations–, Russian continues to play a major role, like Czech in Slovakia. But these countries have made an enormous effort to ensure that their youngsters are practically bilingual in English.

According to an EU legend, an attempt was made at the start of the six-member European Communities to establish French as the sole official language. A high-ranking diplomat conducted a tour of the member states, all of which expressed their approval, except the last, the one that hosted the institutions: Belgium. It opposed the idea on the grounds that it sidelined its second official language, Flemish.

France has lost a significant battle in this struggle and Germany never managed to get a foothold, despite the fact that the languages of both theoretically share the status of working languages with English. Spain never achieved this, since Spanish is spoken relatively little in the EU, and Spain has never succeeded in selling the virtues of Latin America in the European context. This is despite the fact that there are almost 470 million people in the world with Spanish as a mother tongue (second only to Mandarin) and it is the second language in terms of overall number of speakers (mother tongue speakers + limited competence speakers + learners of Spanish), according to the Instituto Cervantes’ latest annual report, El español en el mundo, from 2015. It is the third most-used language on the Internet. However, Madrid lost the battle to make Spanish an official language for European patents, yielding to the dominance of English, French and German in this field.

Participants in the Council of Ministers and the European Council speak whichever language they like, with official interpreters, but English predominates, especially in informal meetings and contacts. Heads of state and government leaders always have their interpreters in tow for one-to-one talks, but they are an exception. And it is an area where Spanish premiers have always struggled. Having said that, it must be conceded that Europe –albeit of a different era– worked well with Mitterrand, Kohl and González, despite their having no language in common, English or otherwise. The European Parliament is a rather different matter, for reasons of democracy. The MEPs usually speak in their own language and rightly so, since in principle they can hail from any social or cultural background.

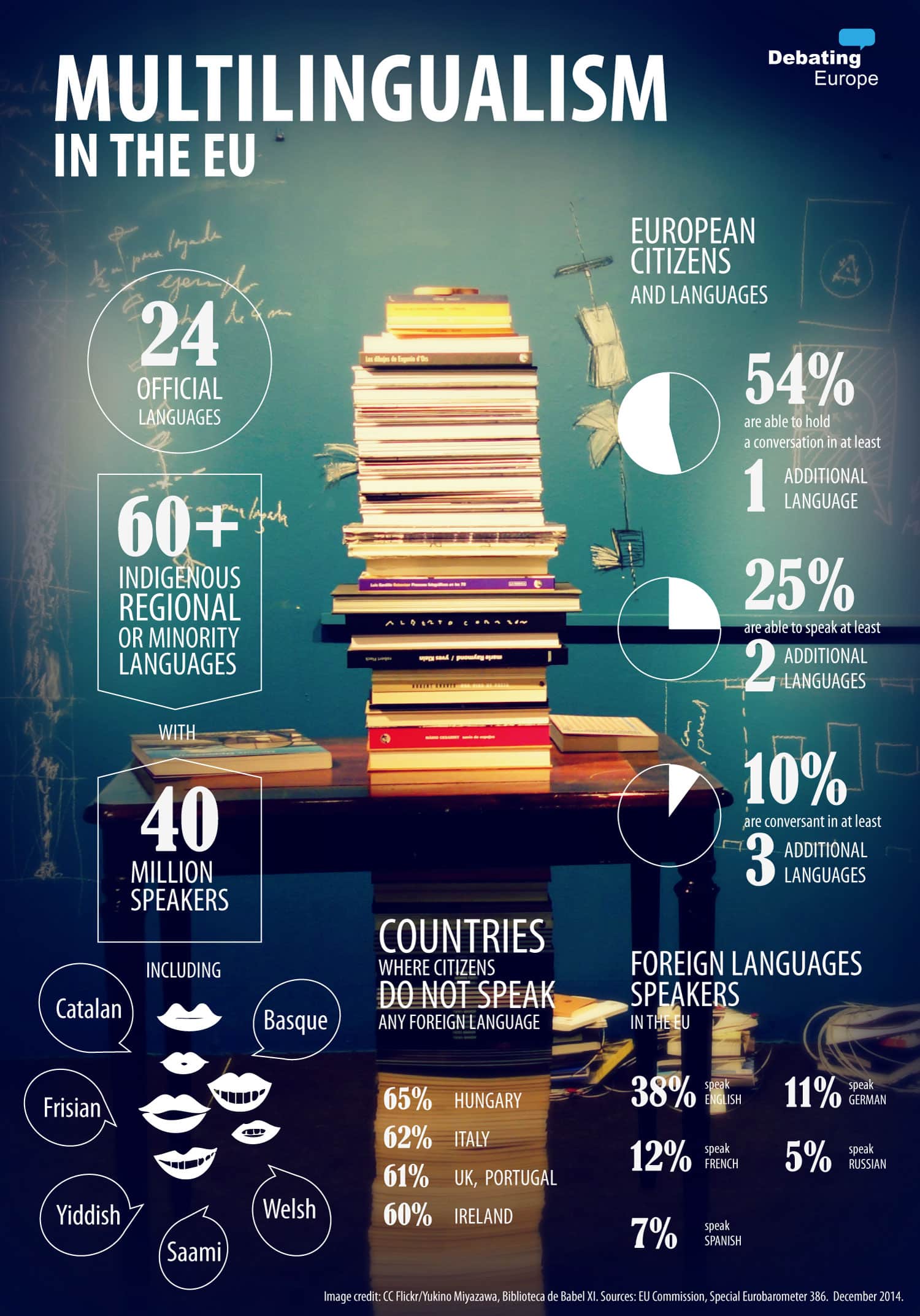

As far as the population at large is concerned, one thing is English as a native language and another as a second or third language. According to a special 2012 Eurobarometer survey, 94% of older secondary school students studied English, compared with 23% for French, 21% for German and 18% for Spanish. Even among younger children, 83% of primary school pupils studied the language of Shakespeare (in its current version), 10 points higher than a decade ago.

Technology is making rapid headway, certainly in terms of software for translating texts, and also in automated interpretation of speech. But this is not to be relied on; rather we must continue exerting ourselves –as indeed we are– to master English, an area where Spain lags behind, Brexit or no Brexit. It is necessary because of what is happening in Europe and in the world. Spain is the country with the lowest percentage of people (22%) in the EU capable of maintaining a conversation in this language.