The Spanish economy is performing relatively well. It grew 0.7% in the first quarter year-on-year, more than double the EU average. The number of social-security contributors surpassed 21 million in May for the first time, underscoring more robust job creation. International tourist arrivals surged 14.5% in the first four months to almost 24 million, putting the country on track for a record 100 million for the whole year. Meanwhile the current account is in surplus. The unemployment rate, however, remains more than double the EU average (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Main economic indicators 2020-23 and forecasts for 2024

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross domestic product | -11.2 | 6.4 | 5.8 | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| Headline inflation (average) | -0.3 | 3.0 | 8.3 | 3.4 | 2.9 |

| Unemployment rate (%) | 15.5 | 14.9 | 13.0 | 12.2 | 11.8 |

| Current account (% of GDP) | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| Fiscal balance (% of GDP) | -10.1 | -6.7 | -4.7 | -3.6 | -3.0 |

| Public debt (% of GDP) | 120.3 | 116.8 | 111.6 | 107.7 | 105.6 |

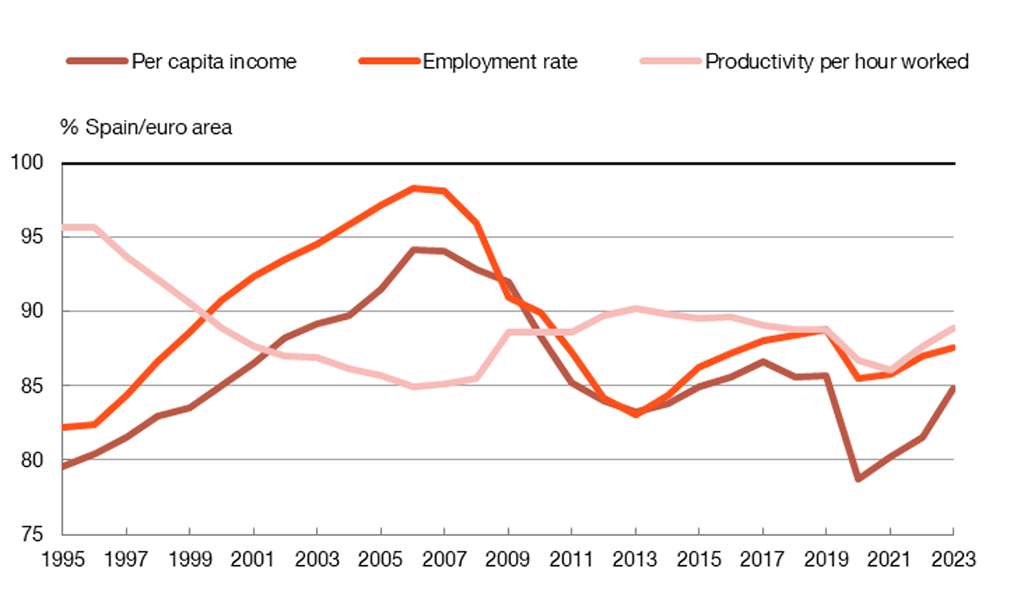

A worrying development is that Spain has stopped steadily converging with the rest of the EU since the 2007-08 global financial crisis. The current gap is 15 percentage points (pp) in GDP per capita (EU = 100; Spain = 85). The Bank of Spain’s governor, Pablo Hernández de Cos, who left the post this month after a six-year term, attributes the lack of convergence to sluggish productivity and the low employment rate (65.9% of the working-age population was employed at the end of 2023, 4.5 pp below the euro-zone average). Productivity per hour worked has stayed between 10% and 15% below that of the euro area since 2008 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Spain’s scant convergence with the euro zone

These problems are, in turn, linked to four longstanding structural challenges: business size and demographics; human capital; physical and technological capital and innovation; and the institutional framework. The corporate sector has a high share of small companies that tend to be less productive; the educational attainment level remains below the EU average; innovative firms are relatively few and R&D spending (1.4% of GDP) is low; and the quality of institutions and of economic agents’ trust in them has declined.

The technological shift, as a result of a greater use of robotics and developments in artificial intelligence, should increase productivity but at the cost of increased unemployment in some sectors and occupations. The OECD estimates 28% of employment in Spain is in jobs at high-risk of automation. This shift is happening at a time when the working population is ageing, due to the declining birth rate, one of the EU’s lowest, and greater life expectancy, the bloc’s highest. This too is impacting productivity. The average employee age so far this century has risen by six years to 43.5.

On the labour market front, says Hernández de Cos, policies are needed to improve employability, particularly for older workers affected by technological change; unemployment benefits should provide sufficient protection without deterring job-seeking; and collective bargaining requires some degree of flexibility to enable employment conditions (including working hours) to adapt to firms’ individual circumstances. The last labour reform reduced the flexibility.

As regards public finances, the fiscal deficit and high public debt make Spain more vulnerable to external shocks. When the global financial crisis was brewing in 2007, Spain had a fiscal surplus, for the third year running, of 2% of GDP and public debt stood at 35.5% of GDP compared with the euro zone average of 66%. Last year saw a fiscal deficit of 3.6% of GDP, down from 10.1% in 2020 when there were exceptional COVID pandemic measures, while debt stood at 107.7% of GDP (with a euro-zone average 88.6%). On the revenue side, the tax system needs an overhaul and spending needs to be made more efficient. The rapid ageing of the population is causing pension expenditure to rise significantly. Analysis of the pension reforms in 2021 and 2023 points to greater long-term spending obligations not being fully offset by revenues. The reforms allow for an escape clause to be activated if the system is out of kilter, but correcting an imbalance solely by raising social security contributions would hit employment.

The impact of NextGenerationEU funds, of which Spain is the second-biggest beneficiary (€77.2 billion in grants, up to €83.2billion in loans and €2.6 billion of RePowerEU) after Italy, is beginning to be felt, albeit more slowly than hoped for as investments are taking longer than expected. Disbursement of the funds is conditional on implementing reforms, such as in pensions, where the jury is out on whether the measures are sufficient.

Hernández de Cos also weighs in on the growing problem of affordable housing for young adults, pointing out that Spain is the EU country with the highest percentage of tenants at risk of poverty or social exclusion (an average of 27.6% since 2014, the highest in the EU). The rise in the population of more than 8 million since 2000 has far outpaced the increase in the housing stock, particularly the rental segment. The stock of social rental dwellings (a paltry 1% of the total housing stock) is almost the lowest among the 38 OECD countries. In the Netherlands it is 35%. The proportion of homes owned by those under 35 dropped from 15% in 2002 to 7% in 2022.

Lastly, following a deep crisis in 2008-14, the banking sector is more financially sound and profitable thanks to a more rigorous regulatory framework, and the ratio of non-performing loans (NPLs) to total loans is low at around 3%. The governor’s remarks were followed by the IMF’s annual assessment of Spain’s financial system which said it has shown resilience against shocks but needed to improve solvency buffers that are lower than European peers on a risk-weighted basis.

Hernández de Cos took over as governor in 2018 when Spain had emerged from the devastating impact of the global financial crisis and the bursting of its massive real-estate bubble, which saw the jobless rate reach 27% in 2013, the collapse of many banks and companies and political fragmentation and polarisation. The economy then took a big hit from the COVID pandemic in 2020 when growth plunged 11.2%, the steepest fall in the EU, and did not recover the 2019 level of output until the second quarter of 2023. Inflation returned with a vengeance in 2022 (at 8.4%).

Under Hernández de Cos’s stewardship the Bank of Spain has modernised internally, becoming notably more transparent and independent in presenting its views, based on rigorous research, and dissenting at times from the government’s policies. Hernández de Cos is widely seen as the most effective governor since Luis Ángel Rojo, who held the post between 1992 and 2000. Like Hernández de Cos, Rojo had headed the research department.

Normally the new governor is known when the outgoing one leaves, but this is not the case this time around. Under an unwritten pact, the government, which is Socialist, chooses the governor and the main opposition party, the Popular Party (PP), the deputy governor. This was not so in 2006 when the then Socialist government went ahead and appointed Miguel Ángel Fernández Ordóñez, a leading member of the economic team of two Socialist governments, without the consent of the PP, which rejected him because he was a politician.

As a result of the dispute, the government also appointed the deputy governor. This time the government is offering the PP a pact if it agrees to help renew the General Council of the Judiciary (CGPJ), which makes judicial appointments and oversees the system and whose five-year mandate expired in December 2018. Its members were appointed during the last PP government. All 20 Council members are chosen by a qualified majority of parliament (requiring agreement between the two main parties).

Hernández de Cos repeatedly called for cross-party consensus for the reforms that Spain needs, though it always fell on deaf ears. He will be a hard act to follow; it would be fitting if, when deciding who will be his successor, his call is heeded and even better if the CGPJ is also renewed by consensus after a disgracefully long saga.