Was George F. Kennan a diplomatic historian rather than a diplomat who wielded influence in government circles? The answer must be in the affirmative because, despite the kudos he garnered as the strategist who advocated containing the USSR from the outset of the Cold War, Kennan faced consistent problems in establishing himself as what in the Renaissance would have been called ‘a counsellor of princes’. From the Eisenhower era onwards, barring some one-off rewards such as the ambassadorship in Belgrade or being invited to take part in the occasional function at the White House, he barely exerted any real influence on his country’s foreign policy. But this does not mean that politicians, journalists and historians have fought shy of quoting Kennan in recent decades or hailing him as the all-time great American strategist; indeed, they have gone so far as to seek out parallels in their own discourse with the views of this singular and unclassifiable intellectual.

When a much-feted biography by John Lewis Gaddis was published in 2011 it unleashed a ‘Kennanmania’ that has still not abated to this day. This may well be due to the fact that we are on the brink of a new era, with an outlook as unknown now as the Cold War must have seemed when compared to the pre-1945 world. People have thus turned to Kennan in search of map references that will help them navigate a world so distinct from the 20th century.

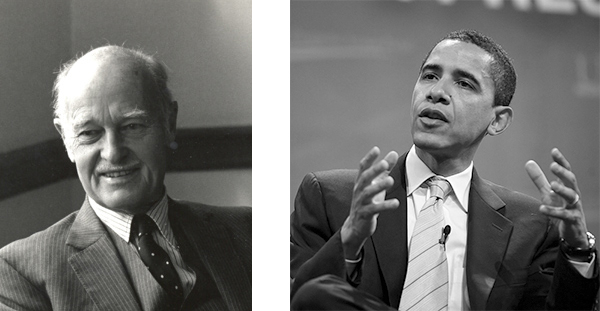

It has been claimed that Obama’s foreign policy operates within Kennan’s parameters of realism. Kennan, like Obama, disliked foreign military interventions, preferring diplomacy and what would later come to be known as ‘soft power’. He opposed both the Vietnam War and the invasion of Iraq in 2003, and was fond of citing a recommendation of John Quincy Adams, the sixth President of the US, who affirmed that ‘[America] goes not abroad, in search of monsters to destroy’. His rejection of the suggestion that the US should be the world’s policeman was, however, offset by a search for equilibrium in international relations. His was a realism that had no faith in victories over ‘empires of evil’, urging instead that diplomacy should avoid greater ills. Combat should be political and psychological rather than military.

By contrast, in an interview he gave to David Remnick for The New Yorker in 2014, Barack Obama said that the US did not need a new grand strategy, or even a latter-day George Kennan. The President went so far as to deny the existence of an Obama doctrine, despite the similarities some adduce between his record and the realism of Nixon and Kissinger, and preferred to talk in terms of historical currents and the need to divert them in one direction or another, given that their final destination cannot be determined. Fareed Zakaria, a foreign-policy analyst whom Obama admires, said at the time that the President believed in organic change and that change comes to countries in very different ways, rather than through the liberation narratives coming from the West.

With an approach such as this, Kennan’s wisdom would not have been appreciated by Obama, as indeed it was unappreciated by earlier presidents. It should not be forgotten that the great strategist of realism was, above all, a historian of international relations, an avid reader who set special store by the role the great works of literature played in trying to fathom human psychology. Obama is also a person who reads widely and peppers his speeches with well-chosen quotations, but he is no historian; rather, he is a brilliant lawyer and political expert in the art of storytelling, frequently practised by presidents since the time of Ronald Reagan. Kennan, by contrast, found unquenchable sources of inspiration in the Bible and Shakespeare, in Burke, Gibbon, The Federalist Papers, de Tocqueville and 19th-century Russian literature. Hence it was said that he longed for the world prior to 1914, although in fact he knew how to blend the ideas and analysis needed to negotiate the uncertainties of the Cold War scenario.

The greatest disagreements between Kennan and Obama would today centre on the Middle East. It is likely that the strategist would criticise the President for not having been able to preserve the region’s geopolitical balance. Seeking a deal with Iran on the nuclear issue should not have been at the expense of provoking the resentment of Saudi Arabia and the Sunni Gulf States, or of Israel. Nor would Kennan have approved of the record on Syria, where the initiative has been left to Russia, Bashar al-Assad’s ally –something else that has gone down badly with Washington’s traditional allies–. And while it is true that Kennan would have approved of the US not intervening directly against the Gaddafi regime, he would not on that account have derived any satisfaction from the chaos that continues to haunt Libya.

But above all he would have criticised the Obama Administration for its reaction to Daesh. The military response would have struck him as inadequate and he would have reminded us, as he pointed out in the context of the USSR at the time, of the need to understand the nature of the movement one is up against. Anything else would be just short-term tactics, not a strategy in which ideas play a crucial role.