The far-left anti-establishment Podemos (‘We can’) is not the only party that is challenging Spain’s discredited two-party system that has given the country stable governments for more than 30 years.

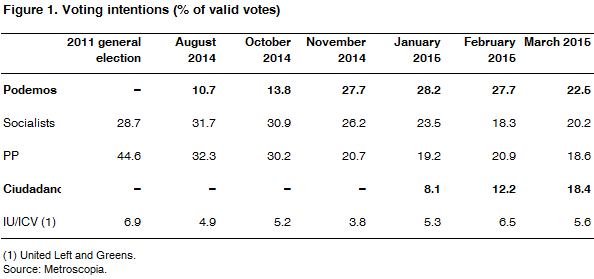

The centrist Ciudadanos (Citizens’ Party) is rapidly gaining support outside of its Catalan base. If a general election were held today it would gain 18.4% of the vote compared with Podemos’ 22.5%, according to Metroscopia (see Figure 1). Podemos, however, appears to have hit a ceiling –its share of the vote has dropped from a peak of 28.2% in January– whereas Ciudadanos continues to rise.

Last November Ciudadanos did not even figure among the most voted parties, whereas Podemos has been on a roll since last August after a stunning result in May’s European elections that rocked the political establishment when it won five seats and 1.2 million votes (8% of the total).

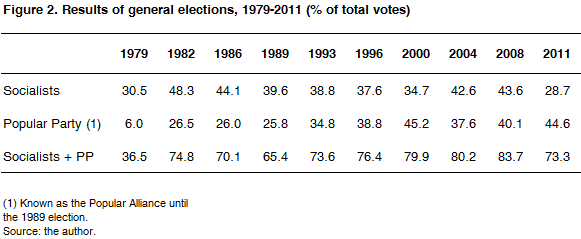

That was the first time the Popular Party (PP) and the Socialists had captured between them less than 50% of the total votes in an election. The two-party system has been in decline since the 2011 general election when the Socialists and the PP obtained between them 73.3% of the votes (85% of the seats in parliament), down from 83.7% (92.2% of the seats) in 2008 (see Figure 2).

The supporters of Podemos and Ciudadanos share a deep dislike of the PP and the Socialists. The level of corruption (endemic in the view of many analysts) in the two parties and their colonisation of institutions, such as the governing body of the judiciary and the national audit watchdog, which has prevented an effective system of checks and balances, is attracting voters looking for alternatives.

Podemos and Ciudadanos also have a common cause in blaming the Socialists for the crisis, sparked in 2008 by the bursting of a massive property bubble, although its roots are much deeper and go back much further, and the PP for the austerity measures.

But the similarities end there. While Podemos is identified with the European communist left and radical Latin American movements, particularly that of the late Venezuelan president, Hugo Chávez, because of the trajectory of its leaders, although it is now trying to pitch itself as Nordic-style social-democrats, the moderate Ciudadanos is seen as market friendly in the economic sphere and liberally progressive in the social (see my commentary on Podemos’ economic programme and on the differences between Spain and Greece’s crisis). For example, Ciudadanos is in favour of a clearer separation than the PP between the Roman Catholic Church and the state.

Podemos labels the political class a ‘caste’. Juan Carlos Monedero, the party’s chief ideologue, refers to Spain’s transition to democracy as the ‘regime of 1978’, in allusion to the constitution of that year which ushered in Spain’s longest period of freedom and prosperity. For those Spaniards who remember the dictatorship the term regime is clearly associated with the Franco period.

Podemos grew out of the grassroots movement of los indignados (the indignant ones) who occupied the Puerta del Sol in the heart of Madrid on 15 May 2011 and set up camp for a month. The 15-M movement was articulated through mobile phones and Internet. Supporters ranged from anti-capitalists, workers who had lost their jobs and pensioners hit by cuts to their payments, to homeowners whose properties had been repossessed because they could not pay their mortgages and university students who saw no future because of an unemployment rate of 25%. What unites them is their anger at the political class.

Podemos is channelling this anger, which could have taken other less democratic and more violent routes, via a party that seeks to participate in the parliamentary system, although it is very critical of that system. This is undoubtedly positive.

Ciudadanos, on the other hand, started life in Catalonia eight years ago and won three seats in the region’s parliament in the 2006 election (nine in the snap 2012 Catalan election). It began to be better known outside of Catalonia after the region’s centre-right nationalist CiU government announced at the end of 2012 that it would hold a non-binding referendum on independence which took place last November in defiance of a ban by the Constitutional Court. Ciudadanos opposed the independence movement.

Ciudadanos won two seats in the European Parliament in last May’s elections (3% of the national vote) and forms part of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe in the parliament.

The party, led by Albert Rivera, a 35-year-old lawyer, defines itself as centre left, although it is increasingly attracting people who previously voted for the PP rather than the Socialists. Its prototype voters live in a city or town, have a degree and are aged between 25 and 54. They have not been as hard hit by the crisis as Podemos’ supporters, who embrace a younger age bracket including the so-called ‘lost generation’ of people between the ages of 16 and 24 who are neither in work, full-time education or training. Spain’s youth unemployment is 55% (around half that including those in education and training).

Podemos’ leader is the 36-year-old pony-tailed and media-savvy political science lecturer Pablo Iglesias. Like Rivera he was born after the end of the Franco dictatorship, but has taken a radically different political path.

Rivera is most approved leader in the latest opinion survey, at 56%, and Iglesias the fifth, at 32%. Pedro Sánchez, the Socialists’ leader, is in third place at 36% and the PP Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy last at 24%. While 98% of respondents said they knew who Iglesias was, only 71% recognised Rivera, suggesting that he has some way to go yet, and with it the party’s fortunes.

There are still 10 months before Spain’s general election, assuming Rajoy does not bring them forward, and anything could happen. What is already clear and unlikely to change very much is that four parties, as opposed to the traditional two, will be competing for power and none of them has anywhere near a clear lead that would enable them to form a government on their own. The current PP government, with an absolute majority, looks destined to be the last of its kind for the time being. Spain has had two minority governments since 1978 but no experience of coalition governments, making it an exception in almost all of Europe.

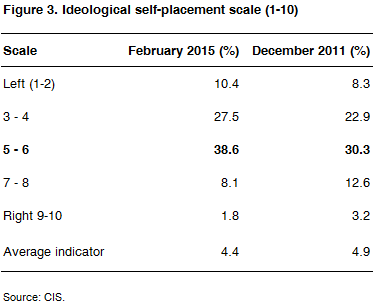

The rise of Podemos would appear to suggest that Spain is moving radically leftwards, but this is refuted by the ideological self-placement scale which over the last 20 years has hardly ever dropped below 4.5, where 5.0 is the centre (10 extreme right and 0 extreme left). The average indicator was 4.4 in February compared with 4.9 in December 2011 when the last general election was held (see Figure 3).

Spain’s electoral system, based on the d’Hondt method of proportional representation, is designed to avoid the fragmentation of power. Any nationwide party that fails to obtain 25% of the votes is under-represented in parliament, while the rules ensure that regional parties are well represented at the national level. The votes won in smaller rural electoral districts are worth more to parties than those won in towns and cities.

Since 1982 the Socialists and the PP have always won more than 25% of the vote, while smaller nationwide parties have been under-represented compared with their regional counterparts. Both Podemos and Ciudadanos need to do well in rural areas if they are to shine in the general election.

Their first test in the national arena, as opposed to the European one, will come on 22 March when they contest the election in Andalusia, which has been ruled by the Socialists since 1982 on its own or backed by the United Left. The region has a jobless rate of 34%, 10 pp above the national average, and is wracked by a mega corruption case. How well Ciudadanos fares in the election could be a pointer to its success or otherwise in the larger picture.