Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy’s gamble that the snap election he called would help return Catalonia, one of Spain’s richest regions, to ‘normality and legality’ did not pay off, as the three pro-independence parties again won a narrow majority in the Catalan parliament on under 50% of the vote and a record turnout of 82%.

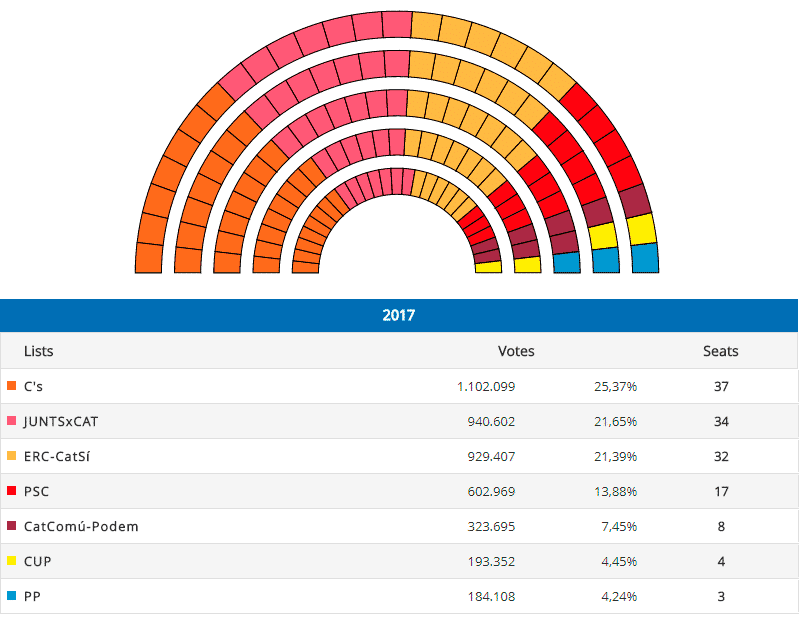

Catalan Republican Left (ERC), Together for Catalonia (JxCat), and the anti-capitalist Popular Unity Candidacy (CUP) won 70 of the 135 seats, while Ciudadanos captured most of the unionist votes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Results of 2017 Catalan election (seats and % of votes) (1)

| Seats | % of votes | |

| JxCat (1) | 34 | 21.7 |

| Catalan Republican Left (2) | 32 | 21.4 |

| Popular Unity Candidacy | 4 | 4.4 |

| Ciudadanos | 37 | 25.3 |

| Catalan Socialists | 17 | 13.9 |

| Cec-Podem | 8 | 7.4 |

| Popular Party | 3 | 4.2 |

(1) Pro-independence parties in yellow.

(2) In 2015, Catalan Republican Left and JxCat (before PDeCAT) went on a joint ticket under Junts Pel Sí. Cec-Podem, in 2015 went by the name Catalunya Sí que es Pot.

Source: Metrocopia.

Its 37 seats, 12 more than in 2015 and a stunning victory (see Figure 2), make it the biggest party, and the first time a non-nationalist party has won a Catalan regional election, but not enough to govern on it own or in coalition.

The other two anti-independence parties, the Socialists and the Popular Party (PP) only picked up 20 seats between them, giving a total of 57 for the three parties, well below a majority (68). The PP, which rules at the national level, lost eight seats and became a marginal party with only three, its worst ever result.

Figure 2. Results of 2015 Catalan election (seats and % of votes) (1)

| Seats | % of votes | |

| Together for Yes | 62 | 39.6 |

| Ciudadanos | 25 | 17.9 |

| Catalan Socialists | 16 | 12.7 |

| Catalunya Sí que es Pot (2) | 11 | 8.9 |

| Popular Party | 11 | 8.5 |

| Popular Unity Candidacy | 10 | 8.2 |

(1) Pro-independence parties in yellow.

(2) Catalunya Sí que es Pot: several leftist parties including Podemos and Initiative for Catalonia-Greens.

Source: Catalan government.

The 11 seats of the far-left Catalonia in Common (Cec-Podem), which has no clear stance on independence, would give the unionist parties 68 seats, an even slimmer majority than the secessionist parties, but this is not going to happen.

The election followed an illegal referendum on independence on 1 October, at which 92% of the 2.2 million votes cast (a 43% turnout) were in favour of secession, and a declaration of a separate state by the Catalan parliament.

The central government responded by imposing direct rule under Article 155 of the Constitution, dissolving the parliament and some of the separatist leaders were jailed. The election was held in abnormal conditions, with the ousted Catalan president, Carles Puigdemont, campaigning from Belgium to where he fled to avoid Spanish courts, while his former deputy, Oriol Junqueras, sat it out in prison in Madrid awaiting trial, like Puigdemont, on rebellion and other charges.

Despite the abnormality, the election –orderly, organised and transparent unlike the unconstitutional referendum– clearly showed the depth of pro-independence sentiment and the profound polarisation of society.

The elections, in which the central issue was independence (other issues were barely mentioned) were as divisive as the Brexit referendum in the UK, and passions ran as high.

‘The republic of Catalonia has won… the Spanish state was defeated. Rajoy and his allies lost,’ Puigdemont told cheering supporters from Brussels. Yet the pro-independence parties (helped by a voting system that favours their dominance in rural areas) won a slightly smaller share of the vote than in 2015 (47.5% vs. 47.8%). The slice of the vote of the nationalist and avowedly pro-independence parties has not changed over the past decade.

The secessionist movement and its nation building feels legitimated, but the 1978 Constitution affirms the ‘indissoluble unity of the Spanish nation.’ The two camps are thus back in the same situation as they were after the October referendum, but with the pro-independence parties emboldened by their election results.

The two main independence parties, Together for Catalonia, headed by Puigdemont, and Catalan Republican Left, led by Junqueras, won 66 seats, four more than when the secessionist movement ran on the same ticket in 2015 under the name Together for Yes.

An immediate question is whether Puigdemont and Junqueras will be able to take up their seats in parliament and for one of them to become the new Catalan president. Both face charges of rebellion and sedition for their part in the referendum, which carry prison sentences of up to 30 years. Police have said Puigdemont would be arrested the moment he sets foot in Spain.

Miquel Iceta, the Socialist leader in Catalonia, proposed that separatist politicians should be pardoned rather than put on trial, if they acknowledged that their unilateral declaration of independence was illegal. He later withdrew the proposal.

The new situation is a big headache for the PP, which has not only not achieved its ambition —and that of the other unionist parties— but also suffered from the surge in support for Ciudadanos, which backs its minority government and will now be looking to eclipse the PP in a future general election, something that could happen sooner than otherwise thought.

Meanwhile, the more than 3,000 companies that have moved their legal headquarters and in many cases also their tax domicile out of Catalonia will not be returning any time soon, and more can be expected to follow. The Catalan economy (one-fifth of Spain’s GDP and one quarter of exports) has taken a hit, with unemployment up, tourism down and investment decisions on hold.

There is no lack of voices calling for negotiations, but each side’s position is now even more entrenched than before. The PP has agreed to study constitutional reform that could give Catalonia more powers, but it is doubtful whether this would satisfy the pro-independence parties.

One option would be to hold a legal referendum, under something similar to Canada’s Clarity Act, which would establish the conditions under which the government would enter into negotiations that might lead to secession.

Whatever happens, the independence issue is not going to go away.