My five years as a PhD student, first in Oxford (Brookes) and then as a post-doc at LSE, have told me that the smart people from the UK, especially those working in the City, see the Euro project thus:

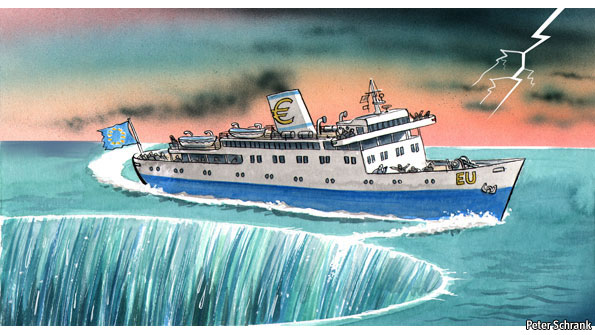

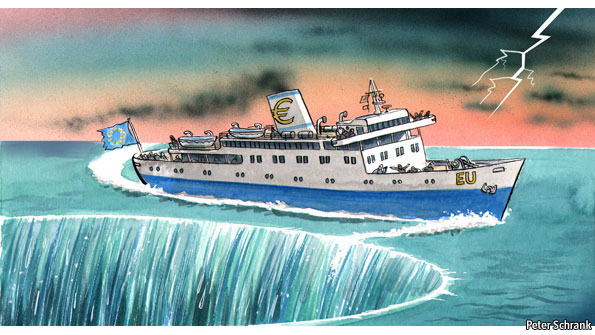

European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) is like a ship that has been built badly from the start. The Brits have warned the Continental Europeans about this structural flaw even before the ship left harbour (think of Thatcher), but the latter wouldn’t listen. They left port anyway, while the Brits stayed ashore convinced that this was a journey doomed to fail.

History has proven the smart people from Oxbridge and the City right. In 2010, confronted with the first big storm (the Global Financial Crisis), the European ship showed its deficiencies and water started to break into the vessel. The Brits screamed: “we told you so”, and enjoyed their Schadenfreude.

However, the ship hasn’t sunk yet. The Continentals are trying hard to fix it while at high sea. They have patched over the leaks for now, although the enterprise is hampered by the divisions in the crew (too many nationalities) and by a lack of leadership. The French and German officers do not agree on the end solution, and the only one keeping the vessel afloat is the Chief Engineer called Mario Draghi.

These troubles make the Brits, and especially the English, feel even more self-righteous about their decision to not join EMU. They are pretty convinced the ship will eventually sink. Nonetheless, they don’t want to be overconfident. They know deep down in their soules that it would be a mistake to underestimate German engineering and French keenness for grandeur so they have a speed boat ready to join at high see in case the ship is eventually fixed. Because one thing is certain. If the ship sails on, the Brits need to have a say in the direction it should take.

This metaphor sums up the view of the City of London in regards to the Brexit debate. In general the Brits have looked at the European Union project from a purely transactional perspective: “What can I get from this arrangement?” This is very different in the Continent, where emotional elements such as angst from your past (Germany), obsession to be bigger than you are (France), desire to belong to a rich club (Italy and Spain and almost everyone else) and fear from your neighbour (the CEE countries) are much more pronounced.

If there is a sentimental bias to be detected among the English (less so among the other Brits) towards the EU it works usually against further integration. The main reason is the British Empire. The Brits have not been invaded since William the Conqueror in the 11th Century and this counts. As a German official told me once: “For the Brits democracy means Westminster. They cannot envision it beyond”. This explains the British obsession to consider the European Parliament as an illegitimate body.

Both the very rational (and so far dominant) approach towards the EU but also the Empire-clinging sentimental rejection against it are very present in the City of London. As a matter of fact, these two perspectives are on opposite sides in the Brexit debate. The former is represented by the big American investment and the European universal banks. They want to stay in the EU because doing so allows them to have access to the biggest and richest market on earth. The latter is usually embodied by the smaller wealth management firms, hedge funds and stockbrokers. They think Brussels curtails the good old English tradition of laissez-faire.

This division is centuries old. The Square Mile of the City is actually the best example of a Global Village. Since London after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 overtook Amsterdam as the world’s most important financial centre, two tribes have co-existed in the City. The “Nativists” (mostly English) who have seen the success of the City intrinsically related to the British Empire. And the “cosmopolitans” (the smartest and more adventurous from the rest of the world) whose functionalist approach has always been the following: “To be as far from politics as possible to make business at ease (the off-shore component of the City being always attractive), but as close to power as necessary in order to influence it”. Thus, London was, and remains, the place to be due to its close connections to Washington and its influence in Brussels.

Of course, if the Brexit camp wins the forthcoming referendum this ideal configuration would change. The City would be further away from politics, and perhaps enjoy less regulation (although that is not assured), but at the same time it would be further away from power (both in Brussels and in Washington) and perhaps even more importantly it would give up completely on joining the EMU ship.

But what happens if eventually the ship gets fixed? Will the smart money of the City of London let it sail away? Unlikely. The ECB is already more powerful than the Old Lady. It will be even more so if EMU survives. This is why Goldman Sachs and the rest of big American and European banks have funded the “Bremain” campaign. They feel the “Nativist” camp led by Boris Johnson is stuck in an imperial illusion which won’t come back. And while they do so, they are thinking: “perhaps we should consider getting closer to Frankfurt. Not only because EMU might get fixed, but also because Westminster is becoming too insular”. And insularity is something you certainly don’t want as a banker.

[This post was originally published on 2 June 2016 in European Notepad]