A few days ago, the European Commission launched its GDP forecasts for next year. Good news are (hopefully) all 28 member states of the EU will record positive variations of their GDP in 2015 for the first time since the crisis erupted. What does this mean for EU’s global presence?

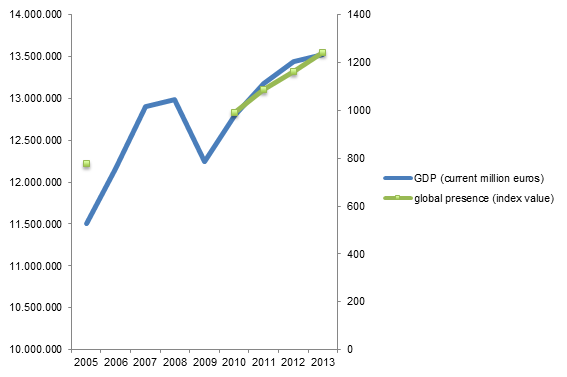

Elcano Global Presence Index calculates global projection of countries –or groups of countries such as the EU– on the basis of 16 different economic, military and soft variables. Obviously, all economic variables –exports of energy, primary goods, manufactures and services and outward foreign investment– as well as several military and soft variables correlate positively with GDP. Therefore, in general terms, there is a parallelism between the evolution of countries’ GDP and their global presence (graph 1).

Source: Eurostat and Elcano Global Presence Index.

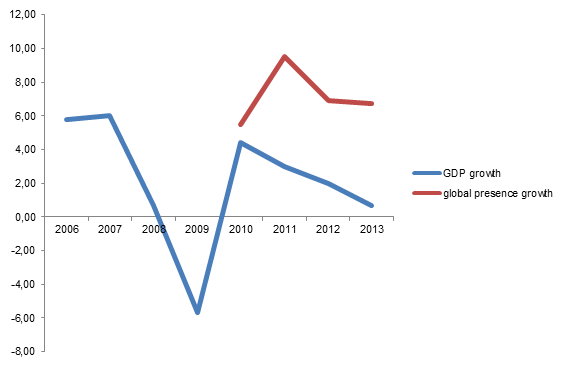

However, for the particular case of the EU, there are also differences between the evolution of global presence and that of GDP. Firstly –and that could be applied to the bulk of countries for which we calculate the index– global presence tends to grow faster than GDP; something that could be interpreted as a sign of the ongoing globalisation process. Secondly, it seems that it takes a while for global presence to react to GDP’s change of trends. The rate of growth of the EU’s external projection slowed down between 2011 and 2012; three years later than GDP growth (graph 2). Therefore, global presence and economic growth can even record opposite trends.

Source: Eurostat, Elcano Global Presence Index and the author’s calculations.

Member states have not necessarily contributed in a similar way to EU’s GDP and global presence (or their growth rates). Actually, growth rates by country show that there is not necessarily a correspondence between negative variations of global presence and decreases of GDP. For instance, in 2013, there was a decrease in the global presence of several Eastern (Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic…) and Southern (Italy, Portugal, Spain…) European countries as well as Belgium and the Netherlands. But GDP in nominal terms fell in only 7 member states (table 1).

Table 1. Annual variations of global presence and GDP of EU member states (2012-2013)

|

global presence |

GDP |

|

|

Austria |

0.33 |

1.70 |

|

Belgium |

-0.35 |

1.80 |

|

Bulgaria |

-1.73 |

0.30 |

|

Croatia |

-0.66 |

-0.85 |

|

Cyprus |

-1.63 |

-6.66 |

|

Czech Republic |

-1.60 |

-2.28 |

|

Denmark |

0.17 |

0.86 |

|

Estonia |

-4.68 |

6.25 |

|

Finland |

0.77 |

1.10 |

|

France |

1.76 |

1.08 |

|

Germany |

-0.87 |

2.17 |

|

Greece |

0.39 |

-6.06 |

|

Hungary |

-2.92 |

1.86 |

|

Ireland |

0.20 |

1.18 |

|

Italy |

-0.78 |

-0.56 |

|

Latvia |

0.00 |

4.72 |

|

Lithuania |

4.17 |

4.93 |

|

Luxembourg |

2.79 |

3.37 |

|

Malta |

9.33 |

4.59 |

|

Netherlands |

-1.86 |

0.34 |

|

Poland |

2.05 |

2.54 |

|

Portugal |

-0.37 |

0.91 |

|

Romania |

-2.04 |

7.83 |

|

Slovakia |

1.08 |

1.95 |

|

Slovenia |

1.12 |

0.38 |

|

Spain |

-1.05 |

-0.57 |

|

Sweden |

0.24 |

3.07 |

|

United Kingdom |

0.80 |

-1.19 |

Source: Eurostat, Elcano Global Presence Index and the author’s calculations.

In the cases of Greece and the United Kingdom, there was a negative GDP variation and a positive global presence variation. The opposite happened in Estonia, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, Portugal and Romania. It could be argued that there is a time lag between GDP records and their impact on global presence (graph 2) but neither Greece nor the United Kingdom have reduced their external projection one single year in the 2010-2013 period.

In short, while there is a rough parallelism between the size and evolution of a country’s economy and its external projection, a more detailed analysis reveals that booms and busts do actually shape the economic, social and political system –having an impact inward / outward orientations of nations–.