Spain’s two-party system is not dead, as predicted, but it took a beating in municipal and regional elections where the upstart parties, the leftist anti-austerity Podemos and the centrist market-friendly Ciudadanos, made big inroads into the ruling conservative Popular Party (PP) and the Socialists (PSOE), which between them have dominated political life for more than 30 years.

The PP gained 27% of the votes cast in the municipal elections, down from 37.5% in 2011, and the Socialists won 25% (27.8%). Between them they captured 52% of the vote, compared with 65.3% in 2011. The PP drew comfort from still being the most voted party, but not by very much. The party, as hoped, is not benefiting from the firm economic recovery and from saving the country from a sovereign bail out by the EU that was on the cards.

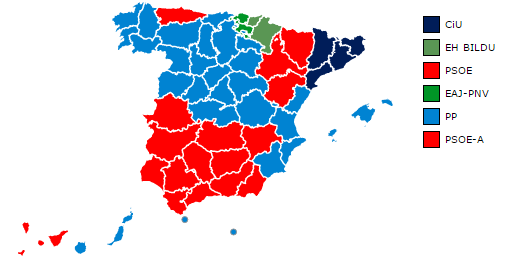

The PP lost its absolute majorities in eight of the 13 regions that held elections (out of a total of 17) including Madrid and Valencia, its two fiefdoms, where it has been badly damaged by a spate of corruption scandals. The PP also failed to win another absolute majority in Madrid’s municipal elections and could lose control of the town hall, after 24 years, if the Socialists back Podemos, which ran under the banner of the Ahora Madrid coalition and won only one fewer seats than the PP. If this happens Madrid’s new mayor will be the 71-year-old Manuela Carmena, a retired judge of the Supreme Court and a former member of the Spanish Communist Party (PCE).

The other significant victory for the anti-austerity Podemos was in Barcelona and also for another charismatic woman, Ada Colau, a 41-year-old anti-eviction activist. She snatched control of the town hall from the nationalist CiU by winning 11 of the 41 seats (25% of the vote), but will need to form alliances in order to govern. Her victory in the Catalan capital was a blow for the independence movement. The Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC), the most pro-independence party, only won 11% of the city’s vote.

Podemos, led by the 35-year-old pony-tailed Pablo Iglesias, was born out of the grassroots movement of los indignados (the indignant ones), which grabbed world headlines four years ago this month when thousands of mainly young people occupied the Puerta del Sol square in the heart of Madrid and set up camp for a month. Voters under the age of 30 played a key role in Podemos’ latest success.

The results of Ciudadanos, led by the 35-year-old Albert Rivera, did not live up to expectations. While Podemos’s support was waning, that for Ciudadanos was continuously rising. Like Podemos, however, it will be the kingmaker in some areas, particularly those where the PP won the most votes but not an absolute majority. Until a year ago, Ciudadanos was hardly known outside its base in Catalonia where it was formed in 2006 to counter, among other things, the growing movement for that region’s independence.

Whereas the 2011 elections saw landslide victories by the PP in cities and regions and heralded its routing of the Socialists in that year’s general elections, this time round the municipal and regional elections suggest a very fragmented parliament when the next general election is held by the end of the year.

An extrapolation of the municipal results shows a parliament with the PP holding 132 of the 350 seats, 54 fewer than now, the Socialists with 119 (nine more), Podemos 16 and five other parties including Ciudadanos with between 10 and 14 seats each. If this proves to be the case, the national parliament could well face the same deadlock as in Andalusia where the Socialists won the March 22 snap election in that region but more than two months later have still been unable to form a majority government after three attempts.

The new political era ushered in by these elections will need coalitions or pacts in many cities and regions if Spain is to continue to enjoy the stable governments that have characterised the country to its benefit since the end of the Franco dictatorship in 1975. The country, however, has very little experience of this, unlike most other European nations.

Spaniards turned against the two main parties not only because of the economic crisis of the last seven years, which has worn down much of the population (the unemployment rate is still almost three times higher, at close to 24%), and corruption, but also because of the high degree of partisan polarisation.

An opinion poll by Metroscopia two weeks before the elections showed that 69% of Spaniards considered it positive that the two parties would not win absolute majorities and that there would be new players on the political scene which would force negotiations.

The PP, the party most affected by corruption cases, did not do enough in the eyes of the electorate to disassociate itself from its bad apples. According to a study by the sociologist Perico García Azorín published this month, 467 mayors around Spain faced indictments, most of them since the onset of the crisis in 2008 resulting from the bursting of the massive property bubble. Of those, 89 had been sentenced and 90 absolved, while the rest still awaited court decisions.

Corruption has been particularly rampant in the PP-controlled region of Valencia, where the party still won the most votes but far from an absolute majority. Around 50 indicted politicians sought re-election in that region, even as they prepared to appear before courts in cases mostly related to the mishandling of public money, despite the PP leader of Valencia, Alberto Fabra, drawing what he called a ‘red line’ under years of corruption.

Turnout was 65% compared with 43% at last year’s European elections when Podemos hit the headlines by winning 8% of the vote and five seats in the parliament. Since then the party has been on a roll.

Podemos’ victories in these elections would appear to suggest that Spain is moving radically leftward, but this is refuted by the ideological self-placement scale which over the last 20 years has hardly ever dropped below 4.5 where 5.0 is the centre (10 extreme right and 0 extreme left). The average indicator is currently 4.7 compared with 4.9 in December 2011 when the last general election was held. A majority of Podemos sympathisers, according to surveys, see this party as far more radical than themselves. Its recent U-turn towards social democracy and away from radical policies has paid dividends, but whether this was merely a tactical move remains to be seen.

Spaniards are not up for adventures and do not want a rupture with the past, which despite its defects is still the best phase of Spain’s history in terms of prosperity, modernisation and peaceful co-existence. The country is living interesting times.