The Elcano Global Presence Index is calculated and updated yearly. Ten new countries are added to the Index database every year. This means that we now have records of global presence index value, contributions (of the economic, military and soft dimension to countries’ external projection) and quotas (held by each country, as a share of aggregate global presence) for 110 countries. That is, nearly 49,000 observations that should help understand foreign policy and international relations.

This Index is merely a tool. Global presence results are not self-explanatory. Rather, they need to be combined with other indicators and, more importantly, with an advanced knowledge of specific countries or regions (including their foreign policy) in order to understand countries’ role in the globalization process and in international relations.

This is why it is so important for the Index team to work with area experts when it comes to analysing the Index results, every year. For one of this year’s publication, we had the luck and privilege of working with two members of the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA), Elizabeth Sidiropoulos and Steven Gruzd, with whom we interpreted the Index results for Africa.

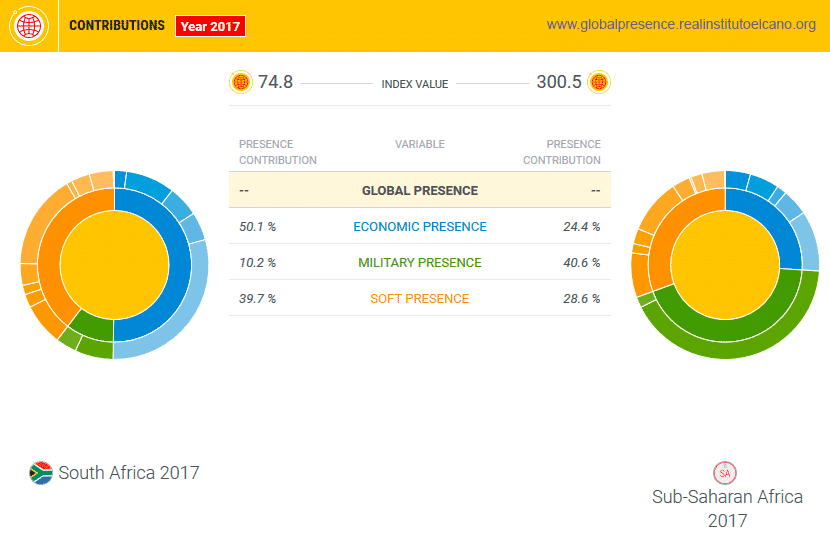

Until 2018, the project had been adding new countries on the basis of one single criterion which is countries’ GDP (in nominal terms and according to World Bank’s figures). As a result, despite a prominent level of world’s representativeness (98% of world’s GDP and 91% of its population), some regions like Central America and Sub-Saharan Africa were under-represented. For this reason, when selecting new countries for the 2017 edition, we limited this criterion to Central American and Sub-Saharan countries. This is how we managed to increase the number of African countries for which we calculate the Index up to 21. Now, 87.3% of the continent’s GDP and 75.4% of its population are included in our project; something that allows for regional analysis.

In late September, we had the chance to travel to Johannesburg, where we had the opportunity of joining our SAIIA’s colleagues for several presentations and vivid discussions on the Index and its results for Africa.

#GlobalPresence @sthembete discussing the @rielcano index. There is interesting intra-African dynamic btwn countries that trying to exert regional leadership although they are very small in global terms. Military dimension continues to play big role in Africa’s global presence pic.twitter.com/uRjf39HDh7

— Elizabeth Sidiropoul (@Siderop) September 26, 2018

Besides the analysis and conclusions included in this year’s report, many additional ideas popped up. Here we will only refer to some of them.

Firstly, Sithembile Mbete underlined the increasing gap, in global presence terms, between Africa and other developing regions (such as the Middle East or Latin America). This can be interpreted in the framework of Africa’s lost decade, in the nineties, and also manifests in the profile of the region’s external projection: hardly no technology (unlike a vibrant Asia and Pacific region) and scarce internal exchanges of goods and services (leading to a low presence in manufactures or even primary goods and energy); a reality that AfCTA might actually change, according to our colleague Ainhoa Marín.

Secondly, South Africa is the Africa’s outlier: a global presence as high as that of Malaysia, Denmark, Norway or Poland; diversified in several dimensions and indicators (with strong records, for African standards, in investments or tourism) and a modest military projection.

The importance of geography (including countries’ size) and of history, and their impact on countries’ global presence was highlighted by Carlos Enrique Fernández-Arias, Spanish Ambassador to South Africa. Developing and emerging small-sized countries that have recently adhered to the globalization process could not possibly record high levels of global presence. Moreover, there is no reason why they should: this is a positive, and not a normative Index. Countries do not necessarily need to scale this ladder unless increasing their external projection becomes a domestic political priority.

The Embassy of Spain and the Ambassador, Carlos Fernández-Arias, participates today in the launch of Elcano #GlobalPresence Report 2018 in Johannesburg. @rielcano @saiia_info pic.twitter.com/ZLO4YsbYx3

— Emb. España Sudáfrica (@EmbEspPretoria) September 26, 2018

We also had a vivid debate on the categorization of countries by regions or blocs. There is a rationale behind the division of these 110 countries into six blocs (Asia and Pacific, Europe, Latin America, Maghreb and Middle East, North America and Sub-Saharan Africa). However, we could opt for other classifications (with other rationales) as we did for this year’s report where North African and Sub-Saharan countries were gathered in an African category. In this sense, Manuel Carvalho, Portuguese Ambassador to South Africa wondered about the impact of Russia in Europe’s global presence (where it is currently included) and on how Europe’s records would change in the absence of this big international player (this is indeed a good idea for another post!).

Lastly, Aditi Lalbahadur pointed out the relevance of breaking down South Africa’s global presence by geographical destination (as we have previously done with Spain). According to Aditi, this could be a valuable input for the analysis of South Africa’s role as a regional leader.

Many other ideas came up, that are food for thought for our future common work. So, thank you, Elizabeth, Steven, Aditi, Sithembile and the whole SAIIA team and friends for helping us understand, think and story tell what the Elcano Global Presence Index is showing about Africa.