The pandemic has been characterised by a notable lack not only of political but also international and even Western moral authorities, of prominent figures –whether leaders in their own fields or intellectuals– to act as beacons of light. Pope Francis from the perspective of Roman Catholicism for example, and the Christian denominations in general, have been unable, or unwilling, to act as such beacons. Nor has the person sometimes referred to as the ‘lay Pope’, the Secretary General of the United Nations, António Guterres, fulfilled this role, while intellectuals with a global audience also seem to have been conspicuous by their absence in the face of this calamity. This is perhaps attributable to the unknown and the sense of impotence arising from a pandemic that requires collective but also individual responsibility. As pointed out, it is a moral, as well as a mortal, malaise.

In the case of other calamities, the impacts in moral and other terms have been considerable. The great pandemics of the 11th and 12th centuries in Europe led people to question the role of religion and the Roman Catholic church and hastened the end of the Middle Ages. A limited catastrophe, such as the Lisbon earthquake of 1755, which had a significant impact on Europe, inspired the great Voltaire to write Candide, a fierce critique of the moral suppositions of the day, especially the idea posited by Pangloss, the protagonist’s tutor, that ‘tout va pour le mieux dans le meilleur des mondes possibles’ (‘all is for the best in the best of all possible worlds’).

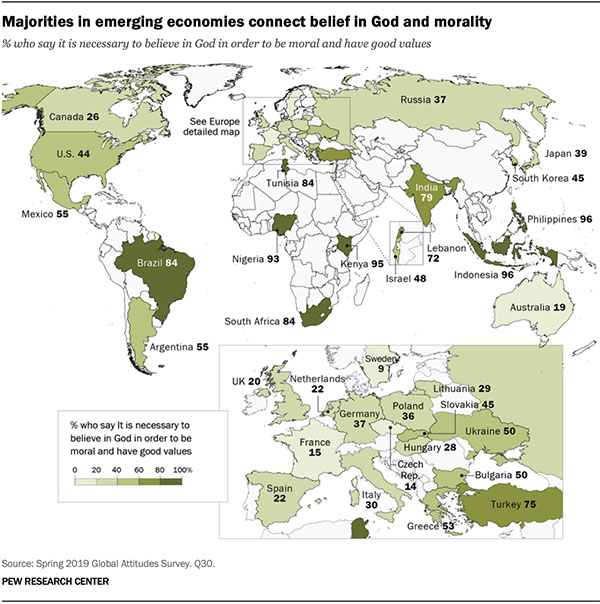

The question of the relationship between morality and religion varies from society to society. A recent (July 2020) poll conducted by the Pew Center suggests that it differs according to country, income and educational levels and age, creating another global divide. Western Europe is a region where a belief in the importance of God as a basis for morality is low, as is generally the case in the wealthiest countries, whereas in Brazil, South Africa, Indonesia and the Philippines it is extremely high. The US is somewhere in between. There are also differences on this issue between the young and old in almost all the regions of the world, with the former placing less emphasis on the connection between God and morality.

It is not that Pope Francis has remained silent. But in his public pronouncements, including the occasional article, he has chosen to steer clear of theological factors, attributing COVID-19 to natural causes and avoiding a religious debate on the issue. Perhaps the Darwinian features of the situation –controlled by the current means of fighting against this type of widespread infection– have reinforced his caution and his calls to safeguard the environment and natural habitats to prevent harmful viruses from crossing into humans. As far as morality is concerned, however, the Pope has emphasised the social dimension, and on the need to combat an inequality that has been aggravated by COVID-19. He has warned against priority for a coronavirus vaccine being ‘given to the richest. It would be sad if this vaccine were to become the property of this nation or the other’. In the preface written by the Pope (who, unlike his predecessor places more emphasis on society and sociology than on theology) to the book Communion and Hope, edited by Cardinal Walter Kasper and George Augustin, Francis argues ‘the crisis has shown us that, especially in times of need, we depend on our solidarity with others. In a new way, it is inviting us to place our lives at the service of others. It should make us aware of global injustice and wake us up to the cry of the poor and of our gravely diseased planet’. But his calls have not had a significant impact on the media.

Pope Francis has backed the initiative launched by Guterres at the UN for a global ceasefire in order to join forces in the fight against the pandemic and to facilitate the efforts of the competent authorities in providing assistance in this regard as well as humanitarian aid to the people most in need. The Secretary General succeeded in getting his proposal converted into Security Council resolution 2532, passed unanimously in July, which refers to the threat Covid-19 poses to international peace and security, although its effects seem limited.

The UN –apart from an inadequate World Health Organisation whose Director General, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, has failed to shine– has generally gone missing in action, due not only to the character of the pandemic, but also to the very deep geopolitical fissures between the permanent members of the Security Council, with increasingly striking tension between the US and China, as well as with Russia. Guterres’s efforts are being focused on ensuring that such tensions do not paralyse the UN even further. As a moral authority he is a long way from a predecessor like Kofi Annan, whose absence is striking.

As far as other leaders are concerned, plenty have become or are becoming autocrats, ‘strong men’ (not women), from Xi Jinping to Putin, by way of Erdoğan and Modi, while for his part Trump has lost all credibility, except among his voters. But these people set amoral or immoral examples. Wars tend to throw up political leaders, but this is not a war, nor are such figures emerging. There is probably a general and widespread decline in the quality of political leadership in the democratic world, and the few exceptions have not secured global influence. Even Merkel, with the strength of her common sense and now heading towards the exit, has not achieved influence on this issue. The absence of leaders is also due in part to the fact that an ‘every man for himself’ attitude prevailed at the start of the crisis, and a national rather than regional or global outlook, with partial exceptions in the EU.

What is taking place can be located within a framework of reference where social movements –which do have a significant moral basis– are unfolding without leaders. The same thing happened some years ago with the Occupy movements in the US, the 2011 anti-austerity movement in Spain, the Me Too campaign and more recently, also in the US but with a much more far-reaching impact, the Black Lives Matter movement. The latter has been a response to the violent deaths of various African Americans, most recently this year, at the hands of the police, hence the recent demonstration against racism in Washington. Community and local leaders take on more importance in this crisis and at these times, with bottom-up micro-leaderships, but not micro-moralities.

Nor have intellectuals been particularly conspicuous as moral authorities, compared to scientists, who do not normally hold such sway. There is always Jürgen Habermas, Yuval Noah Harari and the German-based Korean philosopher, Byung-Chul Han, who argues that ‘the virus is a mirror. It shows what society we live in. We live in a survival society that is ultimately based on the fear of death’. Meanwhile in Spain there is Daniel Innerarity, author of Pandemocracia: una filosofia de la crisis del coronavirus, and others whose publications are scheduled in the weeks ahead. So reflections are under way. Some intellectuals have mobilised in the world for causes linked to the pandemic, such as the 100 prominent Africans who wrote an open letter to their political leaders in May to request that they govern with compassion in the midst of this crisis and view the situation as the chance for a radical change in direction. The virus is blind (although not nihilistic), like nature itself, and the preservation of nature’s internal balances is part of the new morality. It is a far cry from the claim made by Pangloss.