When a widely respected and experienced politician such as Chris Patten, a former Conservative British minister and European Commissioner for External Affairs, suggests that the UK is becoming a failed state it cannot be readily dismissed as an aberration.

We normally associate failed states with countries such as Somalia and South Sudan because of their appalling record of human rights, lack of basic public services, demographic pressures, refugees, internally displaced persons, and security. By these criteria, Britain is nowhere near being a failed state. According to the latest Fragile States Index, Britain is one of the countries less vulnerable to conflict or collapse (determined by 12 different indicators).

Patten, who was also the last British governor of Hong Kong and is the Chancellor of Oxford University, raises the question on the basis of the way the country is currently being governed. ‘Voters elect individual members of parliament, who owe their constituents their best judgment about how to negotiate the predicaments of politics. MPs are not required to do what they are told by an alleged popular will –a system much favoured by despots and demagogues.’ He goes on to say that ‘debates have usually assumed a strong relationship between evidence and assertion’ and ‘historically, government has been accountable to parliament, whose opinions it must respect and whose conventions it should follow’.

Patten says the situation is very different today, with a ‘mendacious chancer’ (Boris Johnson) as Prime Minister who has ‘lied his way to the top, first in journalism and then in politics’, and whose main adviser, Dominic Cummings, who masterminded the Leave campaign in the 2016 Brexit referendum, was described by the former Conservative Prime Minister, David Cameron (2010-2016), as a ‘career psychopath’, and earlier this year was ruled to be in contempt of parliament.

‘Those who oppose crashing out of the EU without a deal are to be branded as opponents of popular sovereignty. So much for parliamentary democracy,’ Patten asserts. The Conservative Johnson is determined to leave the EU by 31 October with or without a deal and rejects another extension of the deadline.

A no-deal would hit the British economy, which is already teetering on the edge of recession, hard. The government’s leaked ‘Operation Yellowhammer’ analysis raises the prospect of shortages of fresh food, medicine and petrol, disruption to ports and the risk of civil unrest, particularly in Northern Ireland where trade across the border with the Republic of Ireland could be severely hampered.

Things have worsened since Patten’s fulmination on 20 August, as the government announced on 28 August a long and controversial suspension of parliament from around 11 September to 14 October when a Queen’s Speech will start a new session.

A suspension is the prerogative of a new government, albeit one resulting from the selection of a new Prime Minister, following the resignation of Theresa May, by 90,000 Conservative members (0.1% of the UK population), and not from a general election. Normally, suspensions are a matter of days (four in 2016) in order for a new government to hold a Queen’s Speech, which sets out the government’s plans.

Parliament was expected to take a break from roughly 13 September to 8 October anyway, so in theory this only loses MPs up to seven parliamentary days. But the suspension, at a critical moment in the UK’s history (when was the last such momentous decision taken as leaving the EU?), reduces Parliament’s scope. Parliamentary sovereignty is to be emasculated in the name of restoring it.

Supporters say suspending Parliament (which rejected May’s EU withdrawal deal three times) respects the 2016 referendum by guaranteeing the UK leaves the EU on 31 October, with or without a deal, while John Bercow (a Conservative), the House of Commons Speaker, described it as a ‘constitutional outrage’. A legal challenge has been mounted against the suspension by among others, Sir John Major, a former Conservative Prime Minister

With the countdown to a suspension of Parliament underway and so time is of the essence, Bercow allowed MPs to vote on 3 September on a motion brought by a Conservative MP to not allow a seemingly likely no-deal Brexit. The government was defeated by 328 votes (21 of them Conservative ‘rebels’ including the grandson of Winston Churchill) to 301 and lost its wafer-thin majority of one when an MP joined the Liberal Democrats. A furious Johnson responded by saying he would have the rebels expelled from the party, so stripping them of their right to vote in the next election.

The bill was expected to complete its passage through the Lords on 6 September, giving it time to obtain the royal assent before Parliament was suspended. Johnson then has until 19 October to either pass a deal in Parliament or get MPs to approve a no-deal Brexit. Once this deadline has passed, he will have to request an extension to the UK’s departure date to 31 January 2020, with no guarantee of a Brexit deal.

Johnson was also defeated on his plan to hold a snap election on 15 October as he did not obtain the required support of two-thirds of MPs. Having spent the last two years calling for an election, Jeremy Corbyn, the Labour leader, changed his tune. He would support an election once the non-deal Brexit becomes law. Johnson would fight the election on the slogan of ‘the people’ versus parliament, further deepening the divisions in the country.

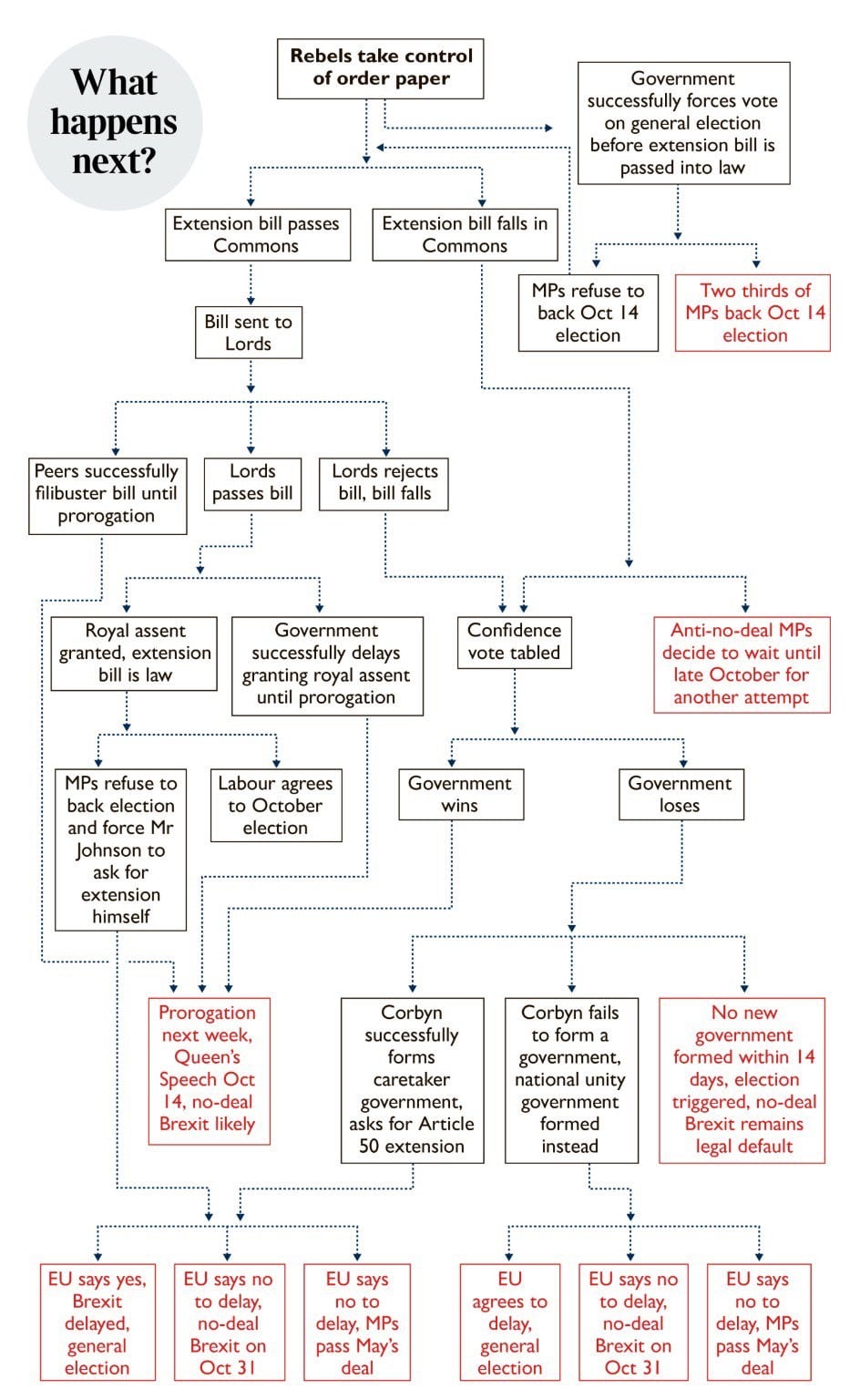

The UK is now in an extraordinary situation. Parliament (often referred to as the Mother of Parliaments) is locked in a showdown with government, and the country has its most serious constitutional crisis since the 17th century. Meanwhile the value of sterling is falling (around 20% since the referendum), investment in the UK by foreign firms has declined sharply, businesses still cannot plan for the future with any certainty and the Brexit issue is consuming all energy to the exclusion of other pressing issues such as education. What are the ways out of this dog’s breakfast? The possible scenarios are set out in the chart below (texts in red).

Furthermore, the break-up of the Union of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland is now being openly talked about. Both Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to remain in the EU. Nicola Sturgeon, the Scottish First Minister, says the decision to suspend parliament may have made independence ‘completely inevitable’, while a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, in the event of a no deal, imperils the 1998 Good Friday Agreement and could strengthen the cause of a united Ireland.

Not only does the end of the union seem more likely, but so few supporters of it appear to care. Only 30% of British Conservatives (officially the Conservative and Unionist Party), and only 14% of Brexit Party voters, would oppose Brexit if it meant the break-up of the union, according to a You Gov poll.

The UK political system has long prided itself for pragmatism and avoiding extremism. This is no longer the case. Britain is not a failed state in the generally accepted meaning (one whose political or economic system has become so weak that the government is no longer in control), but the body politic is failing to deliver in the best interests of the country as whole.

But that perhaps is inevitable when a referendum is held on such a complex issue as leaving the EU, and with a 50% threshold that was far too low for such a fundamental constitutional issue, and is narrowly won on the basis of simplistic arguments and lies whose propagation was greatly helped by social media.